50 Powerful Travel Photography Tips To Dramatically Improve Your Images (+ free downloadable PDF)

Travel and photography always seem to go hand in hand.

When we’re exploring a new part of the world, an exotic environment that stimulates and invigorates our senses, many of us feel compelled to capture the highlights, the special moments, the visual spectacles that we witness during the journey.

After all, many of us spend the greater part of our lives sitting behind a desk in a sterile office looking at the screen of a computer.

We get to dedicate a much smaller proportion of our lives to exhilarating pursuits like sailing the high seas or skipping through Edenic valleys filled with wildflowers in far-flung lands.

The photographs we take during our travels help us to preserve those rare good times; they help jog our memory when we revisit them in the future, allowing us to almost relive the experience again, long after the memories of the trip have become a blur.

“Once you have traveled, the voyage never ends, but is played out over and over again in the quietest chambers. The mind can never break off from the journey.”

– Pat Conroy

No matter how tedious or monotonous daily life becomes, our travel photos can always, in an instant, mentally transport us back to that enchanting land of vibrant colours, sunny weather and happy people that we once experienced, even if only as a fleeting holiday.

Our travel photos also serve to assist those friends and family members who were not fortunate enough to accompany us on our trip, to understand the import and the sublimity of what we have experienced during our time away.

Our verbal accounts can only communicate so much, but when images accompany the narrative, the story is more complete and our listeners can better relate and truly understand what we have been through.

Perhaps we also wish to take travel photos because of their commercial value; we might like to sell prints, exhibit our portfolio in a photo gallery when we get home, use our images to create a website or a popular social media page, or sell our work on stock photography websites.

Regardless of the underlying motivation for taking photographs during our travels, the better and more compelling our images are, the better they will serve our purposes.

We’ve all experienced that sense of disappointment and regret in the past when the photographs we’ve taken in a bid to capture a key moment during a trip have completely failed to do justice to how the scene looked, how it felt, how we felt.

People want to improve their travel photos for a wide variety of reasons but the tips and advice for improving them are the same for everyone.

I’ve put together here the most comprehensive list of travel photography tips on the web; 40,000+ words of no-nonsense, no-fluff advice gleaned from my own experience of travelling around the world for over 5 years while photographing everything of interest that I've encountered along the way.

This guide is divided up into three sections.

Section 1 covers general photography tips that don’t deal with any specific gear or techniques.

Section 2 focuses on gear and accessories that you’d be wise to invest in if you’re looking to improve your travel photography.

In Section 3, I delve into a number of intermediate to advanced techniques that can be used to create compelling and emotive effects in your images.

Most of the information you need to execute these techniques is in the guide but wherever there is a more involved editing process required for the technique I have linked out to one or two tutorials dealing with that subject.

Without further ado then, let’s dive right into my best photography tips that are going to help you to start creating images that have the power to truly captivate and inspire people.

1. Section 1: General travel photography tips

1.1 Track down great shooting locations

1.2 Take a photography tour or workshop

1.4 Rise early to beat the madding crowd

1.6 Your photos need a compelling subject

1.7 Learn the fundamental principles of composition (and then break them)

1.9 Know your camera like the back of your hand (and keep it well maintained)

1.10 Don't neglect to use your camera's viewfinder

1.11 Learn how to shoot in manual mode

1.12 Improve the technical quality of your images

1.13 Editing is a necessity, not a means of deception

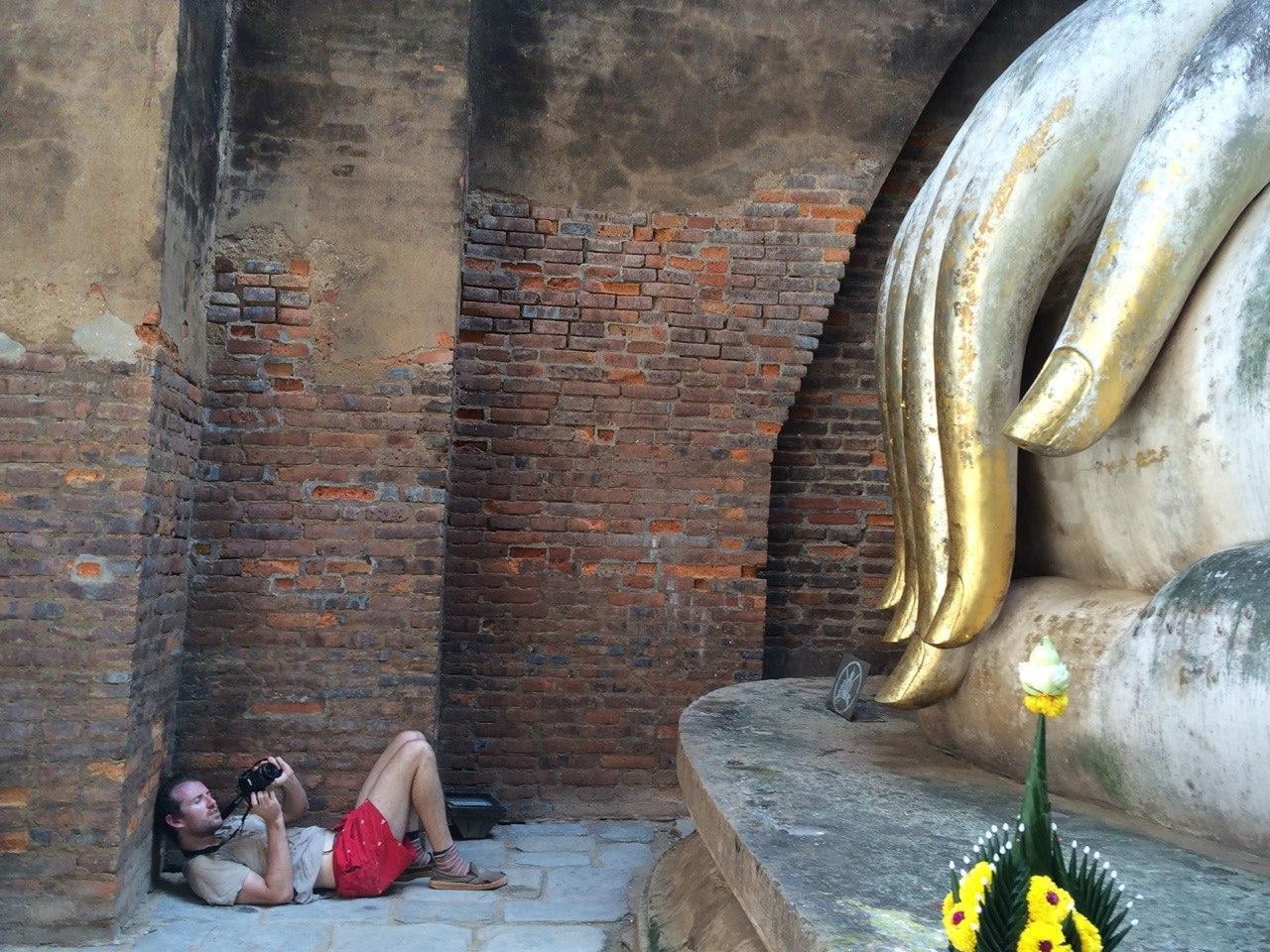

1.15 Sometimes you need to think completely outside the box

1.16 It's okay to do a little "gardening"

1.17 Try shooting from moving vehicles to capture rarely photographed subjects

1.18 Look for interesting ways to frame your subject

1.19 Use the power of storytelling to make your images more compelling

1.20 You miss all the shots you don't take

1.21 Carry plenty of spare memory cards and batteries

1.22 Ask local people for permission before taking their photograph

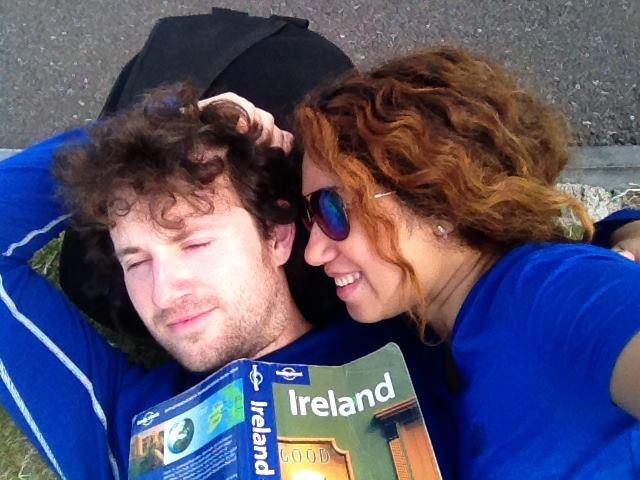

1.23 Every photographer needs a muse

1.24 Slow down and try to live more in the moment

1.25 Always stay true to yourself

1.26 Make the most out of every opportunity (always give 100%)

2. Section 2: Photography gear and accessories

2.1 Get a tripod (+ a remote release)

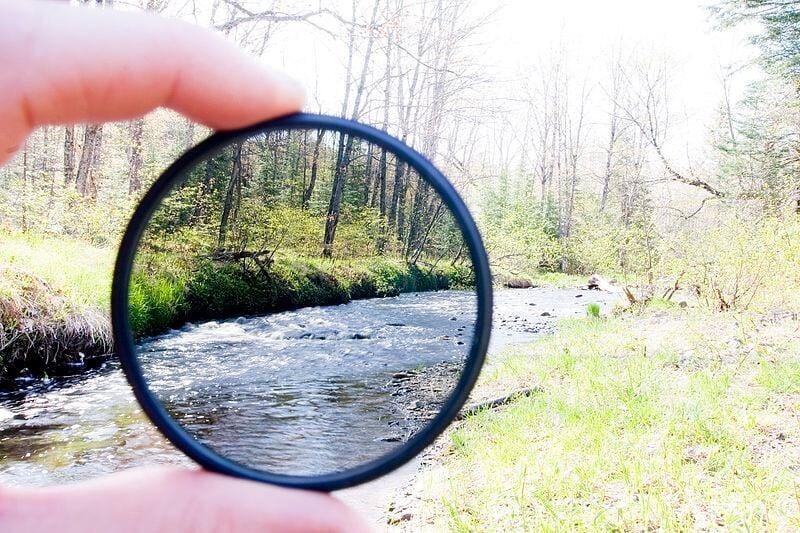

2.2 Invest in the right filters

2.3 Use a lens hood to block stray light and prevent washed out images

2.4 Convert your standard lens into a macro lens with a macro reversing ring

2.5 Buy a drone for aerial photography

2.6 Pack a selfie stick (maybe)

2.8 Supplement your primary camera with an action camera

2.9 Get a dome port for your GoPro if you're into underwater photography

3. Section 3: Useful techniques to enhance your travel photography

3.1 Become a master of time with long exposure photography

3.2 Create motion blur without long exposures

3.3 Add beautiful sun stars and starbursts to your images

3.4 Use the power of scale to surprise and impress your viewers

3.5 Always keep an eye out for reflections

3.6 Convey a sense of depth in your photos

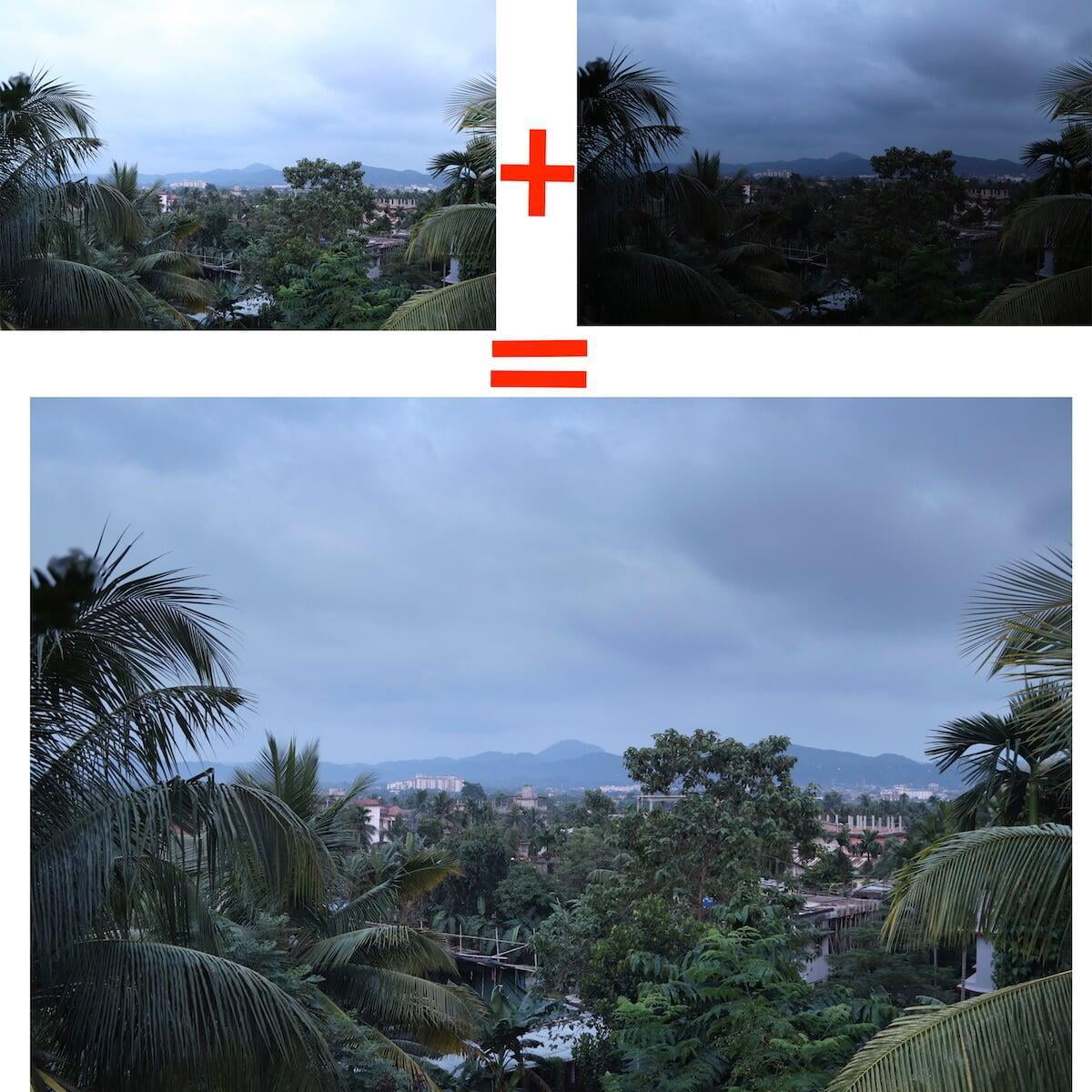

3.7 Panoramas are a secret weapon

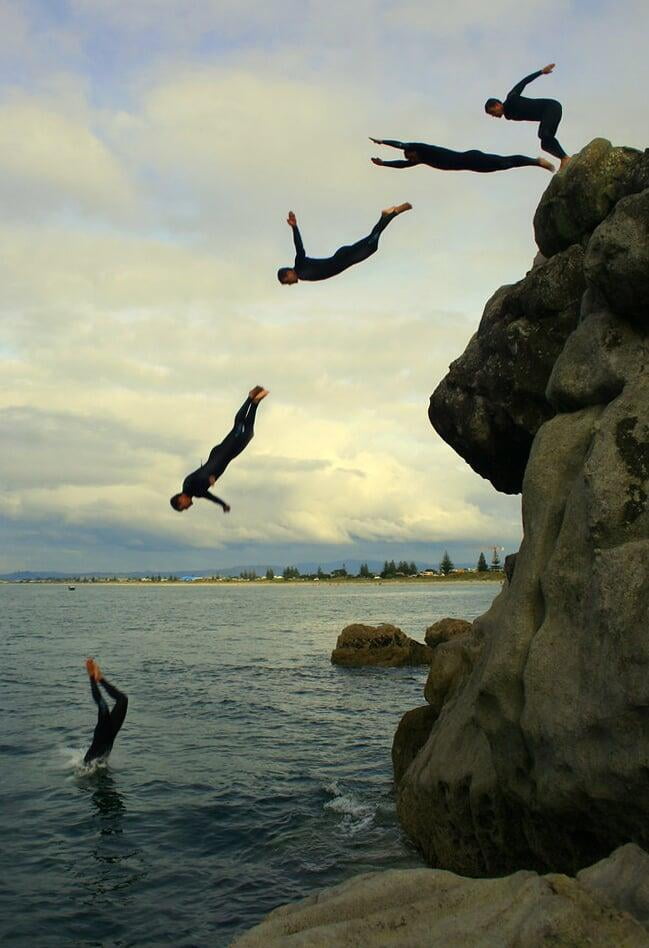

3.8 Give multi-frame action sequences a try

3.9 Try shooting against the light (backlighting) for a change

3.10 Learn how to create mysterious silhouettes

3.11 Beautify your backgrounds with good bokeh

3.12 Overcome depth of field limitations with focus stacking

3.13 Use leading lines to improve your compositions

Section 1: General travel photography tips

#1 - Track down great shooting locations

Just as in real estate, the mantra for travel photography is also location, location, location.

No matter how good a photographer you are, it’s exceedingly difficult, if not completely impossible to create stunning images from drab subjects or humdrum scenes.

Sure, great photo-ops can sometimes unexpectedly materialize in mundane settings, but success is most reliably achieved by tracking down great photography spots.

Compelling travel photos capture subjects, landscapes and environments that are unique, exotic or out of the ordinary, and these are not found everywhere.

You have to think a bit like a predator, like an animal in pursuit of its elusive prey; those who seek out secluded jungle waterfalls, death-defying sea cliffs, ice-capped peaks and other elusive locations will be rewarded with the most sublime images.

Yes, taking truly great travel photos does require you to be something of a pioneer, an explorer, a swashbuckler imbued with the spirit of adventure.

But how can you find these great photography locations?

Here are a few pointers.

Explore beyond the madding crowds

Most tourists just follow the herd and that’s why a lot of their photos from a certain landmark, attraction or national park can look samey.

Even if you only ever visit the popular attractions that everyone else flocks to, you can find unique photo opportunities just by venturing a little further afield than the crowds.

If the majority of tourists tend to snap photos of the front face of the building, why not investigate to see if any interesting shots are to be found around the backside?

If the unenterprising masses normally only climb the mountain as high as the first viewpoint, why not continue on to see if there are even better viewpoints higher up? Why not go all the way up to the summit if you have the energy?

As the well-known saying goes, “the best view comes after the hardest climb.”

One thing I’ve learned in all my years of travel is that being willing to go the extra mile and push myself that little bit further has often rewarded me with spectacular photo opportunities that I would never otherwise have gotten.

Of course, sometimes all that extra exertion can be for nothing too, like when you finally reach the peak after a tough uphill slog only to find that thick trees are obstructing would otherwise have been a sublime view.

But usually, as if by dint of cosmic justice, there will be a treat in store for you to recompense you for your travails.

Follow your curiosity

This tip relates to the last one, but it also applies more generally, even when there are no crowds of tourists around or when you’re not actively shooting.

Often, it will be your innate curiosity that will lead you to discover a new photo-worthy location; maybe you’re curious to know where that dirt road near your guest house leads to, or what that strange-looking cluster of boulders in the middle of that distant green field is all about. Maybe it’s a little-known cousin of Stonehenge?

It doesn’t matter if the location you're drawn to isn’t in a guidebook and in fact it’s all the better if it isn’t because it means that you might become one of the first people to photograph it.

So don’t be afraid to investigate some of those relatively unexplored nooks and crannies and diversions that might lure you away from your original plan or program. Follow your instinct and great photo opportunties will reveal themselves. The journey matters more than the destination.

Of course, curiosity will probably lead you to a dead end in more instances than not, but that’s the price you have to pay to find worthwhile new photo spots It’s a process of trial and error..... and mostly error.

Use Google to scout for locations with potential

Into landscape or architectural photography?

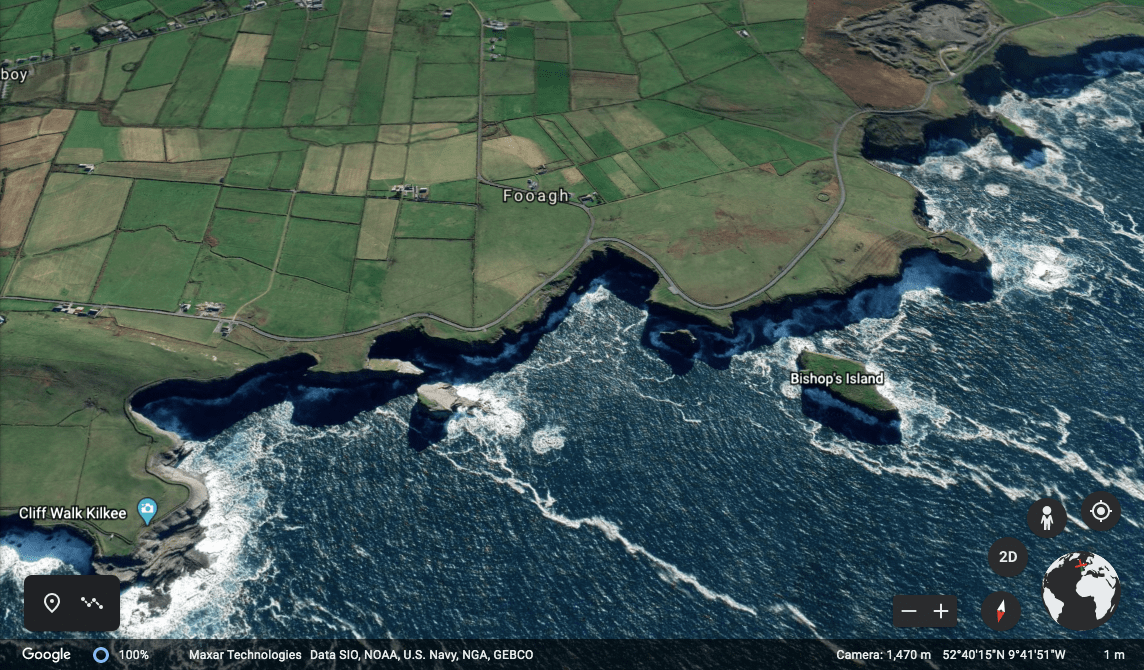

You can use Google Maps and Google Earth to scout out potentially interesting landmarks, buildings and geographical features in your destination.

Potentially interesting locations in and around your destination, like the confluences of rivers, horseshoe bends, lakes, dams, sea cliffs, sea stacks, sandy beaches, lagoons, historical buildings, bridges, and so on can all be easily identified just by looking at a map.

Once you’ve discovered a potential candidate, you can get a fair idea about whether the location has photographic promise by entering the name of the place into Google images and then browsing through some of the photos that were taken at that location by other people.

Ask locals for suggestions

If you’re going to find a secret or unique spot that hasn’t been photographed much by outsiders, it’s probably going to be a local that tells you about the place, since the locals know the hidden gems of their area better than any outsider who writes a guidebook.

Even local people who are not into photography will probably be able to suggest a few scenic locations that you might otherwise have never known about, but it’s even better if you can meet a local photographer and persuade him to let you in on all his favourite spots.

A great way to connect with locals is through Couchsurfing, BeWelcome, Warm Showers, Servas, GlobalFreeloaders and other hospitality exchange websites. See our article on how to sleep for free while travelling for more information about these platforms.

Another way to meet locals is through work exchange or volunteering platforms like HelpX, Workaway, Worldpackers and WWOOF.

Other platforms and apps geared towards tourists having experiences with locals are Withlocals (find local hosts that offer private, personalized tours) and Eatwith or VizEat (enjoy authentic local culinary experiences with local hosts).

Airbnb can also be a way to connect with locals, although some of the hosts are absentee landlords that you probably won’t be able meet during your stay.

You can also just connect with locals in the old-fashioned way – you know, by initiating conversation with people that you encounter in the physical world? Does anyone ever do that anymore?

Hire a local guide

An experienced local guide may be able to take you to some secret or offbeat locations that aren't covered in any travel guidebooks or websites. Some of these little-known places will surely have photographic promise. If the guide is a photographer or knows a thing or two about photography, even better.

In many cases, local guides will approach you soon after you arrive at a destination, long before you even go looking for them.

When we visited Yangon's Shwedagon Paya, the most sacred Buddhist pagoda in Myanmar, a local guide approached us while I was taking photos of the monument.

He wanted to show me a few of the pagoda's secrets so that I would be able to photograph them, although I declined his offer, as I wasn't sure how much he was going to try to charge me after revealing the secrets.

One way to get a free local guide is if you use Couchsurfing to sleep in locals' homes and have them show your around their local area. Although some Couchsurfing hosts will be too busy with work and other commitments to give you a tour, other hosts will dedicate their time to you and will be able to show you some really cool places.

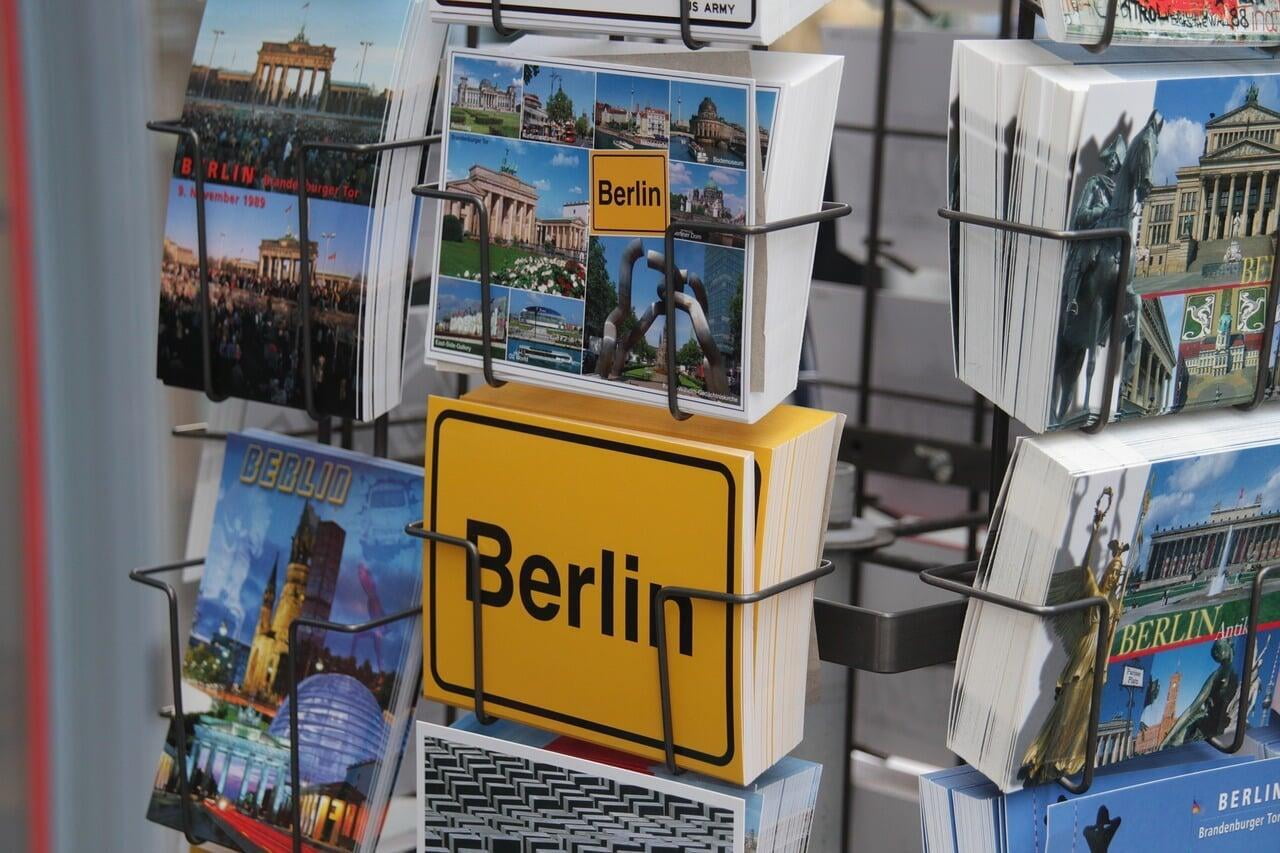

Look for local photography spots in postcards, art galleries, museums, guest houses etc.

Whenever I visit a new destination, I always pay close attention to the postcards that the shops are selling (if any), as some of these images will usually have been taken at prime photography locations in the locality.

In some towns you’ll find art galleries, commercial photo galleries and even paintings being sold on the streets by local artists; these will often depict picturesque scenes in the vicinity, although you might have to ask someone to tell you the exact locations.

Your guesthouse might also have framed photographs or paintings mounted on the walls depicting interesting scenes from the local area or from the country in general.

You are more likely to find these prideful exhibitions of art and local culture in characterful, family-run accommodation, and far less likely to find it in cookie-cutter hotels that usually just mount some kind of generic painting (like a sailing boat) on the wall above the bed.

Local museums often have interesting photo galleries and exhibitions too, although the photos in museums often only depict scenes from times gone by, and may not reflect the present reality.

Tourist information offices are another good place to look for leads, and if you don’t find too many framed pictures on the walls inside the building, you’ll surely find them in the promotional brochures and flyers that they hand out for free to any tourist that drops in.

Join photography communities and follow creators you like for inspiration and recommendations

While it’s important to always be on the lookout for novel or underexploited photography locations, there's also nothing wrong with visiting well-established locations recommended to you by fellow photographers and travellers.

Following other people's suggestions can often be very rewarding, although it shouldn’t be your only strategy for finding new photo opportunities, lest you become a copycat and end up with a portfolio that's predominantly filled with unoriginal material.

You can see what other photographers are up to by following them on image-sharing platforms and communities like Instagram, 500px, Flickr and Imgur. See this list for more photo-sharing websites.

There used to be a great image-sharing platform called Trover that was dedicated exclusively to travel photography, but sadly it had to close down in August 2020 after being in operation for 9 years.

Travel slow and explore your destination thoroughly

The best travel photo opportunities in any destination often only reveal themselves after some digging and after spending a lot of dirt-time in the field, exploring an area thoroughly.

If you spend longer than most people spend exploring a destination – say a few weeks instead of just a few days - you’ll have extra time to discover photo opportunities that the average visitor who only sticks around for a short time will probably miss.

The fewer stones you leave unturned, the higher the likelihood that you’ll eventually stumble across the hidden gems and leave with the best possible images of your destination.

Be willing to invest money to access prime locations and better photo opportunities

While there are gazillions of spectacular photos to be had for free in this world, many do unfortunately lie behind a paywall.

As you already surely know, popular tourist attractions and national parks with aesthetically pleasing sights often charge visitors a fee for entry, which puts photographers who aren’t able or aren’t willing to pay at a disadvantage.

While you can often still capture a few decent photos from the periphery without entering the actual site, you are inevitably going to have to forego the photo opportunities that are exclusively available to those who ponied up the entry fee.

We have written an article describing how entrance fees at tourist sites can be circumvented in many instances, but much of the time it’s simply not possible to do so due to ticket checks and close monitoring of access points.

Being willing to spend money during a trip can unlock new photo opportunities in other ways too.

For example, if you are willing to pay to rent a traditional costume, a colourful umbrella or some other interesting prop from a local opportunist at a tourist spot, it will help to embellish your photographs.

If you're into photographing people, some locals may demand a tip or bribe (known as baksheesh in India) in exchange for their portraits, although this mostly only happens in touristy destinations where certain local personalities with exceptional aesthetic value have gotten used to being barraged with requests for photographs and have started trying to capitalize on the demand.

Usually you can avoid paying this tax, as it's typically a case of "photograph me first, pay the tip before you leave" and often the subject will not mention money at all until after the photo has been taken.

Once you've taken the desired picture (s), can always shake your head and deny payment if you feel a person or group of people is being greedy or is trying to take advantage of the situation.

But if you meet a person who is demanding payment in advance or who tries to get you to agree to a price for a portrait photo beforehand, you will have no choice but to pay.

Those who are willing to fork out for expensive accommodation will often land rooms with sweeping balcony vistas or might find themselves staying in heritage hotels (converted from erstwhile palaces, forts, castles, mansions etc.), which boast enthralling traditional architecture and elaborate interior décor that set an appealing backdrop for photos.

With that being said, many budget accommodation options can also offer guests superb views from the rooms, especially if it’s a naturally stunning location where you’re staying, like Vang Vieng in Laos.

#2 - Take a photography tour or workshop

Photography tours and workshops are one way to ensure that you get a chance to photograph many of the most photogenic locations that your destination has to offer.

In the case of the photography tours, they’re usually just a glorified whistle-stop sightseeing tour in a bus.

You can expect the tour guide to take you to various locations with photographic potential, but you won’t get too much hands-on instruction on how to take the actual photographs once you’re there.

Photography workshops, on the other hand, involve much more intensive in-field instruction, critiquing/reviewing of photos and post-processing instruction every day from dawn to dusk. You’ll probably be travelling around in car or a 4 x 4, and will make unplanned stops if something interested is observed on the way to a location.

If you’re already highly accomplished in photography and just want to be shown the best spots, then a photography tour might suit you best, whereas if you feel your skills are lacking and you want to really improve them, a workshop would be the more appropriate choice.

To find photography tours and workshops for your destination, you could do a Google search and you could also check tour-booking websites/apps like Viator and Klook.

You can also look for tours and workshops offered by locals on apps and websites like WithLocals, TourGuide, ShowAround and AirBnB Experiences.

#3 - Chase beautiful light

Every good photographer knows that the type of available lighting in a scene can often either make or break the photograph.

There is no specific type of lighting that is always desirable or always undesirable, although certain types of lighting are rarely of interest to photographers.

When the light is on a photographer’s side, even a normally uninspiring scene can be rendered photo-worthy, while a scene that should be very evocative can lose much of its appeal when the lighting Gods are frowning upon the photographer.

While there is no specific type of lighting that is always desirable (good) or always undesirable (bad), we can speak of certain types as being generally advantageous and other types as being generally disadvantageous.

Let’s first talk about when you are very likely to get favourable lighting conditions.

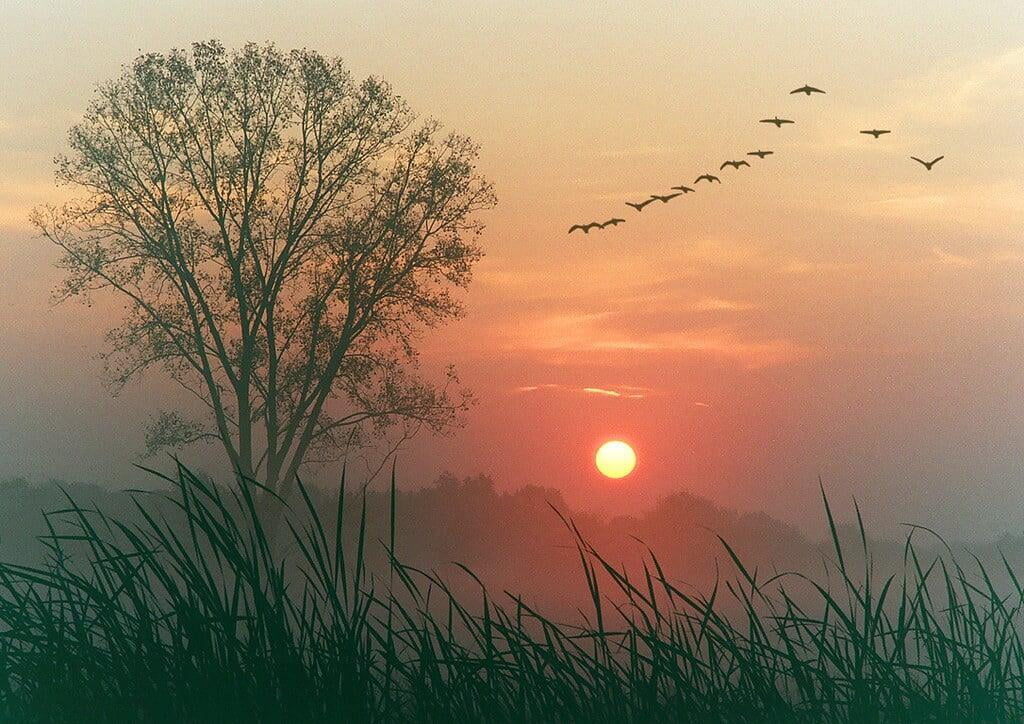

Favourable lighting for general travel photography is very likely to occur in the early morning after sunrise and in the late afternoon before sunset.

The hour following sunrise and the hour preceding sunset are known as the “golden hour” or “magic hour”, due to the ethereal, golden-coloured sunlight that's produced at these times, weather-permitting of course.

When landscapes and subjects are bathed in this warm, golden-coloured sunlight, their aesthetic value is greatly enhanced in the eye of the beholder.

If you are not sure about the golden hour timings for a particular location, you can use this golden hour calculator. This website defines the golden hour as the period when the sun lies between the horizon and 6° above. They also have The Golden Hour App (only available for iOS).

The website displays a map of the world that you can click on to find out the exact times the sunrise and sunset golden hours begin and end for the place on the map that you clicked on.

To view the golden hour timings for sunrise and sunset you need to scroll down to the panel below the map and hover your mouse pointer over the vertical yellow bands. You can also click on different dates in the calendar here to see how the timings vary with the time of year.

So that's a handy tool for finding out the golden hour timings for your location, but how do you know if the sunset or sunrise is likely to be any good and that it won't be completely clouded over?

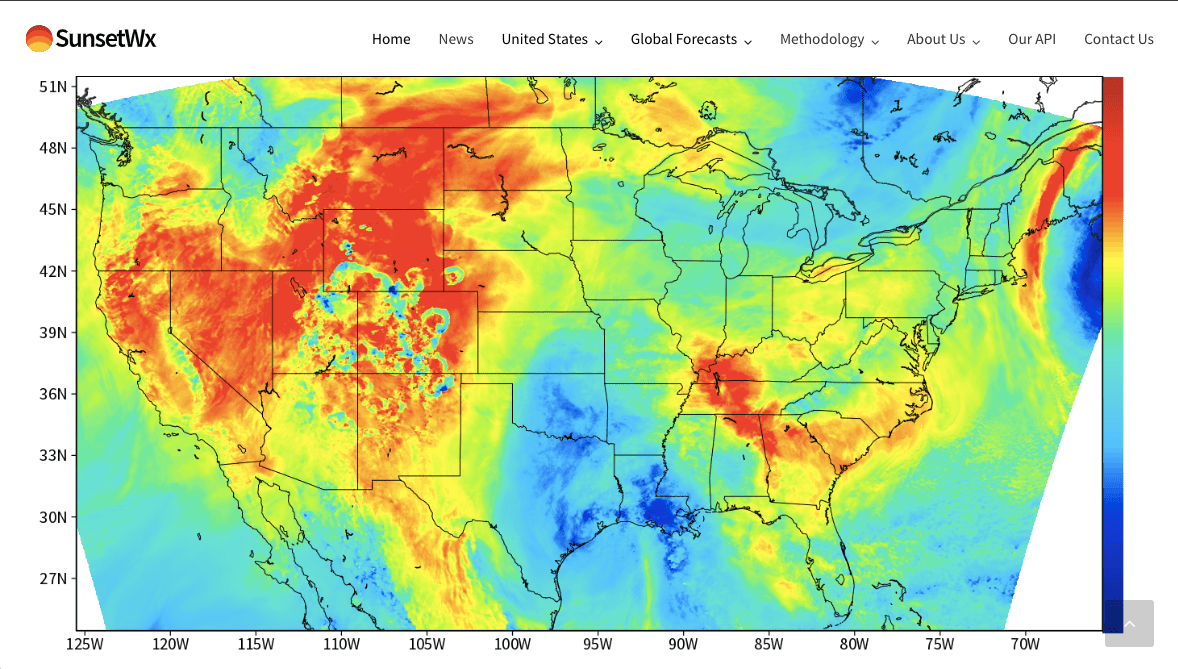

Well, I have often relied on local knowledge and weather forecasts for this, but there is also a website called SunsetWx that can forecast the quality of sunsets and sunrises.

The site is currently only forecasting across North America, but maybe they'll expand to other countries eventually. The forecasts are displayed as a heat map of the continent, where the closer the colour on the map is to red, the higher the probability of a jaw-dropping sunset in that area.

When the magic hour ends and the sun disappears below the horizon many photographers will pack up their tripods and put away their cameras, but this so-called "blue hour" or twilight period when day transitions to night can often be the time when the most incredible light patterns can form in the sky.

It's often well worth waiting for 20-30 minutes after the sun has gone down to see if any interesting colours or light patterns develop in the sky. Sometimes you'll see a brief burst of red or purple in the sky if you're willing to hang around, but you'll need to be quick to capture it, as I've found these extraordinary bursts of light to be very short-lived.

While every photographer loves shooting during the magic hour, many forget that cloudy, moody or overcast weather can also provide very favourable lighting conditions for photography, especially when photographing people or wildlife.

When the skies are clouded over, the light from the sun is diffused through them and becomes what's known as “soft light”.

Soft light or diffuse light is more even and does not create the harsh shadows that are produced by the direct, hard light that comes from the sun when it's high in the sky on a cloudless day.

If you are photographing people you will usually get much better results with the soft lighting that's present on overcast days, as there won’t be any harsh shadows eclipsing areas of your subject’s face (i.e. raccoon eyes) or glaringly bright spots where the sunlight is falling.

Dark grey skies bearing foreboding cumulonimbus storm clouds or other interesting cloud formations can also make for great “moody” landscape images.

In fact, images with clouds are almost always more interesting than those with featureless blue skies, because clouds impart drama to a photo.

I’ve taken several good pictures with skies bearing ominous rainclouds while travelling in various Asian countries during the monsoon season, a time of year when these countries see far fewer visitors as a result of the frequent afternoon thunderstorms accompanied by heavy downpours.

The only issue with shooting on cloudy days is that the light levels can be significantly lower than on sunny days, which means that, if shooting handheld, you will usually have to increase your camera's ISO setting to 200, 400 or even higher in some cases, thereby introducing more noise into your images.

However, if for those photos that will allow you to use a slower shutter speed, you can use a tripod and set the ISO setting much lower to avoid producing additional noise.

Another occasion when you might be granted very favourable lighting conditions is when the clouds break after a rainstorm.

As the clouds disperse, you'll often witness these amazing "god rays" of light bursting through the openings like spotlights beaming down on the landscape from heaven.

If the storm breaks in the late afternoon or early morning, the effect can be stunning as the light rays breaking through the clouds bathe everything in golden magnificence.

Rainbows are another wonderful natural light phenomenon that can add a touch of magic to any photograph. Rainbows result from an interaction between the white light from the sun and water droplets that are suspended in the atmosphere.

They form when the sun's light gets dispersed (refracted) upon entering, and then again upon exiting a water droplet. The dispersed light exits from the same side of the droplet that it enters, having been reflected off the inside of the droplet.

You can often witness rainbows when it's raining and sunny at the same time, or when the sun is interacting with the fine mist created by waterfalls, water fountains, water jets and so on. Your chances of spotting one are greater in the early or later parts of the day when the sun is lower in the sky.

When trying to locate a rainbow, you should stand with your back to the sun and look towards the rain, waterfall, fountain or other feature that's producing water droplets.

If you are very lucky you might even witness a double, triple (tertiary) or even a quadruple (quaternary) rainbow, although the last two are exceedingly rare.

Double, triple and quadruple rainbows form when light reflects two, three and four times inside a water droplet respectively, as opposed to reflecting just once, as it does for a regular single rainbow.

Also, triple and quadruple rainbows can only be seen by looking towards the sun, unlike single and double rainbows, which are observed with the sun to one's back. Triple and quadruple rainbows actually form around the sun, being centred on it, which can make them difficult to spot.

If you’re shooting indoors, you will usually get the most agreeable light near a window or beneath a skylight where natural light is streaming in from outside.

Artificial lighting in a building is often dimmer and doesn’t have the same appealing quality as the natural daylight that pours in through a window.

Of course, window light is only really useful if you’re shooting a person in an indoor environment, and it won’t be available unless there’s a window or skylight (or several) in the room or building.

So, those are some examples of favourable lighting. But what about unfavourable lighting? Are there times when you shouldn't bother shooting?

Many photographers will tell you that on sunny, cloudless days, the worst time for shooting most types of outdoor scenes is around midday.

This is because the sun is highest in the sky at midday and the light is very hard and direct (it's softer when the sun is lower in the sky in the early morning and evening), casting harsh, undesirable, hard-edged shadows across landscapes, buildings and people's faces.

However, while the intense midday sun may not always afford you the most advantageous lighting, it doesn't mean that you can never take great photos under these circumstances.

There are actually certain types of photos that work very well under strong lighting conditions (i.e. backlit trees, rolling landscapes, macro-scale scenes, black and white photos etc.) and sometimes you might want the high-contrast lighting to convey a certain message or mood to the viewer.

You can also always try to find some shade if you find that the harsh midday lighting just isn't working for you.

In other words, there's no hard and fast rule here, and there are many circumstances where it is possible to take great photos in outdoor scenes during the middle of a cloudless, sunny day.

I would advise that you don't restrict yourself to shooting at any particular time of day and that you learn how to make the most of all the different types of outdoor and indoor lighting conditions.

Many photographers will restrict themselves to shooting during the magic hour only to be disappointed when they arrive at the scene to discover that the lighting wasn't what they expected it would be.

You can never be 100% certain that there's going to be a spectacular sunrise or sunset lying in store for you, as nature is unpredictable and ultimately has the final say here.

And if you do get lucky enough to witness a magnificent sunset you should never wait until the sun gets too close to the horizon before taking your photos.

I've made this mistake before myself and watched in horror as, just when I was getting ready to take photos, the sinking sun suddenly disappeared behind an opaque wall of haze that was hanging above the horizon.

I went home that day without anything to show for that beautiful sunset because I didn't take any photos when I had the opportunity, when the sun was not yet obstructed by the atmospheric haze but was still a bit higher in the sky than I wanted it to be.

When you're travelling I recommend going out and shooting at any chance you get, as you can't capture everything during the magic hour; it would take too many days to photograph all the interesting locations at your destination if you were only out shooting for 1-2 hours each day at sunrise and sunset.

Lots of photos of a trip are better than very few, even if many of those photos were taken under suboptimal lighting conditions.

I recommend reserving the locations that you know will make for exceptionally beautiful or romantic photos for the magic hour slot of the day, and then shooting the more prosaic spots at other times of the day.

#4 - Rise early to beat the madding crowd

“Dawn is the time when nothing breathes, the hour of silence. Everything is transfixed, only the light moves.”

- Leonara Carrington

While the golden hours at sunrise and sunset can both present very favourable lighting conditions for photography, the morning window presents an additional advantage over the evening one; fewer people tend to be around.

While I’ve often witnessed large crowds of tourists gathering at popular sunset spots, the crowds that gather at sunrise spots will typically be smaller, since a lot of people just can’t be bothered or don’t have the willpower to get out of bed that early in the morning.

To reach some vantage points in time to witness the sunrise, tourists might have to set out from their hotel at 2 a.m. or earlier and hike for hours in the pitch dark, like that time we climbed Gunung Merapi (a highly active volcano) in central Java, Indonesia.

We had barely arrived at the crater summit of Mt. Merapi when the first welcome rays of the morning sun breached the horizon and began to warm our chilled bones.

Climbing 1,300 vertical metres from the village of Selo to reach the peak of Mt. Merapi was quite onerous and is a challenge that I imagine many people wouldn't be willing to undertake.

There’s a much higher likelihood that you’ll be able to obtain those immaculate, tourist-free images if you can arrive at the popular spots at the crack of dawn (or at least before it opens) in order to beat the crowds. Your images will be refreshingly devoid of distracting elements and you won't have to deal with people obstructing your shots.

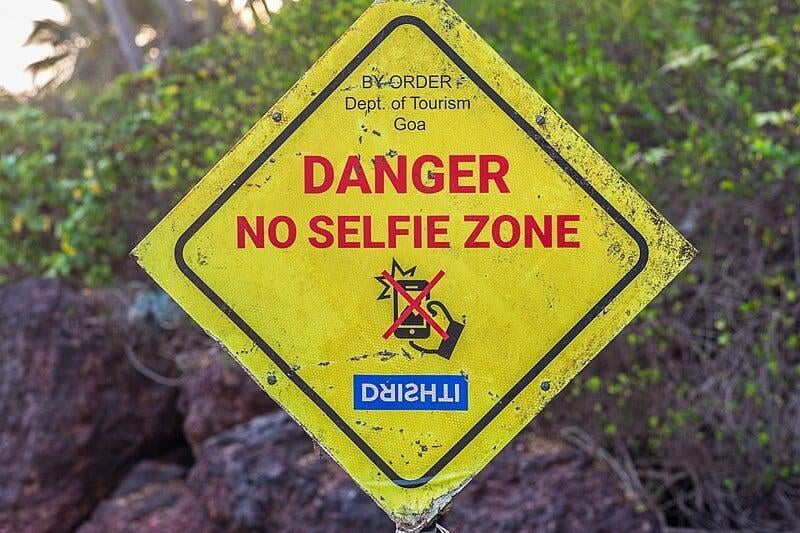

There’s something almost magical about having a sight that receives thousands of tourists daily entirely at your own disposal, even if it’s only yours for a few minutes before the hordes of selfie-stick wielders storm the gates and overrun the place.

That electric atmosphere, that pin-drop silence, that feeling of exclusivity that you experienced will be almost palpable in your images.

A deserted location also means that you won’t have to spend a lot of extra time in Photoshop afterwards trying to remove tourists who inadvertently or deliberately spoiled your perfect shots from your images.

The well-known proverb “the early bird catches the worm” definitely applies here.

#5 - Get your timing right

Finding great locations is hugely important in photography, but many photos are also time-sensitive and to nail them you must not only be in the right place, but also be there and press the shutter button at just the right time.

After all, many scenes in the real world are not static and they change with the passage of time, both in the short-term (by the second, minute, hour, day) and in the long-term (over the time span of weeks, months and years).

Having some level of understanding of how places change in the long-term and according to the seasons or time of year is vitally important when it comes to planning your trip.

It's not that any particular time of year is "better" for photography than any other, but many places will appear different depending on when you visit.

If you want to capture a lot of beautiful sunrises and sunsets during your trip, then you need to be paying attention to the climate of the destination you're visiting and plan your visit during the drier months.

If you're aiming for a postcard look in your photographs, then dry, sunny weather is generally best, especially for photographing beaches and coastal areas.

Sandy beaches will look perfect for sunbathing and the sea will appear calm, blue and inviting (as opposed to grey, turbulent and menacing), making the scene beckon to holidaymakers.

On the other hand, if you want a moody or foreboding look in most of your images, then you should plan to visit during the wetter months when the skies will be grey with threatening storm clouds much of the time.

The rainy months are also the best time to photograph waterfalls, as there'll be plenty of water in them whenever there's a downpour. Many waterfalls are dependent on rain and can remain little more than a trickle running down a bare rock face for months until the rains arrive.

Not only that, but the cloudy or overcast weather that you'll get most of the time during the rainy season means that you won't have to deal with high-contrast lighting that will give you blown out highlights where the sun is reflecting off the water, and very dark shadows where it's not.

Additionally, the lower light levels on cloudy days means that you can often take long-exposure shots of waterfalls without having to use an ND (neutral density) filter, which can add an unwanted colour cast or vignetting to your images.

If you're trying to photograph natural flower displays you really need to get your timing right, as many flowers have a narrow peak bloom window lasting just a few days or weeks at best.

Many photographers travel to Japan and South Korea to photograph the magnificent displays of cherry blossoms during the sakura season and the peak bloom window typically only lasts for about 7-10 days from the end of March into the first week of April.

Upland valleys of flowers, such as the enchanting Dzükou Valley of Nagaland and Manipur states in northeast India, also have their peak bloom windows. In the case of the Dzükou Valley, it's the first two weeks of July.

Some flowers can only be photographed once every several years, such as the purplish-blue "Neelakurinji" flower (Strobilanthes kunthianus), which only blooms once every 12 years in Eravikulam National Park, which is located near the hill station of Munnar in the Nilgiri Hills (part of the Western Ghats) of Kerala, India.

The last time Neelakurinji flowered was in 2018 and prior to that was in 2006. It usually blooms for about 3 months, from August until late October.

Many travel photographers will also plan their trips to coincide with certain festivals and other special occasions, as great photo opportunities during these types of events can be a million times more forthcoming than at other times of the year.

We never actually planned a trip with a festival in mind (as we hardly ever plan anything), but some of our past trips have coincided with important local festivals by sheer happenstance.

For example, the famous Tawang Festival coincided with our visit to the town of Tawang (2,669 m) in the mountains of Arunachal Pradesh in October 2017.

As well as understanding how long-term and seasonal changes affect the appearance of places, you also have to be highly attuned to the short-term changes that affect a scene as the day progresses and while you're in the process of shooting.

If you want to shoot a waterfall on a sunny day for example, you have to think about what direction the waterfall is facing and time your visit accordingly; if it's facing west then you might want to visit the waterfall in the evening when the sun will be illuminating it. But if you want to shoot the waterfall while it's in shadow, then the morning would be the best time to visit.

When you arrive at the shooting location the changes continue; variations in the light intensity and type (soft light vs hard light) caused moving clouds alternately covering and revealing the sun, elements exiting the scene and new ones entering, elements changing position within the frame, and so on.

There are usually two types of elements in any scene being photographed; static elements that always remain fixed and never move, and dynamic elements that can change position and enter and exit the scene.

Static elements are objects like buildings, trees, rocks, roads, railway tracks, parked vehicles – things that don’t move or don’t move very much.

Dynamic elements are things like the sun, moon, stars, clouds, rivers, waterfalls, waves, people, birds, animals, moving vehicles – things that are moving or are liable to move.

In any given scene, dynamic elements may or may not be present, but whenever they are present, the timing of your photo becomes very important.

In other words, when all the elements in a scene are static, it doesn’t matter when you press the shutter button, but when the scene has moving elements, you will get very different results depending on the exact moment that you pull the trigger.

If you're shooting scenes with walking people or moving vehicles in your frame, you'll often want these moving elements to be positioned in a specific area of the frame, and to accomplish that you'll need to wait and then press shutter button at just the right moment.

Another example when timing is very important is when you’re trying to photograph a bird in tree, which keeps disappearing behind foliage and then re-appearing again, hopping around on the branches and constantly turning its head this way and that.

You'll ideally want to press the shutter button at just the right moment, like when the bird is side-on and is making eye contact with the camera lens.

Of course, the desired moment will not always arrive immediately, and when it does it may be very fleeting, so you will probably need to wait very patiently for it while maintaining your concentration on your subject.

This is why patience can be a very important human quality to have in photography.

But sometimes patience isn't enough, like when that perfect moment you’re waiting for is too ephemeral for it to be captured deliberately.

For example, a butterfly perching on a flower spreads its wings for a split second, displaying a flash of vibrant colour, but by the time you react to the photo opportunity and press the shutter button the creature’s wings have already closed up again.

One way to get around this problem is to use the continuous shooting feature that most cameras come with nowadays. Also known as burst mode, it’s basically like spraying bullets, where your camera fires off a number of shots in rapid succession.

Afterwards, you sift through all the shots you took in burst mode and pick out the one that was (hopefully) captured at just the right moment.

#6 - Your photos need a compelling subject

It might seem self-evident that every photo needs to have a compelling subject, but a lot of people apparently forget this basic principle of photography when they capture images like this:

But what is wrong with the above image?

Well, it feels a bit empty doesn't it?

Like it's missing one crucial component?

While the lake has quite an interesting shape, it's still not interesting enough on its own to really capture your attention and draw you into the image.

The photo would be a lot more engaging if there was something out on the lake, like a boat perhaps. The problem is that the image lacks a clear subject.

The subject can be defined as the element or elements in a scene that you want to draw the viewer’s attention to.

It’s the focal point of the image, the thing that the photo is really “about”. It's the specific element in the scene that captured your imagination and made you think “wow, this is really cool”.

When a photo lacks a subject, the viewer is left scratching his head. He or she is unable to figure out what the photo is about, what message the photographer was trying to convey or why the photographer even took the photo in the first place.

A subject-less photo leaves no lasting impression and the viewer will grant it little more than a fleeting glance before turning their attention elsewhere.

Luckily, when you're travelling, there are fascinating things to photograph almost everywhere and anything that captures your attention in real life should be a worthy subject for a photo, as if you found it awesome, other people probably will too.

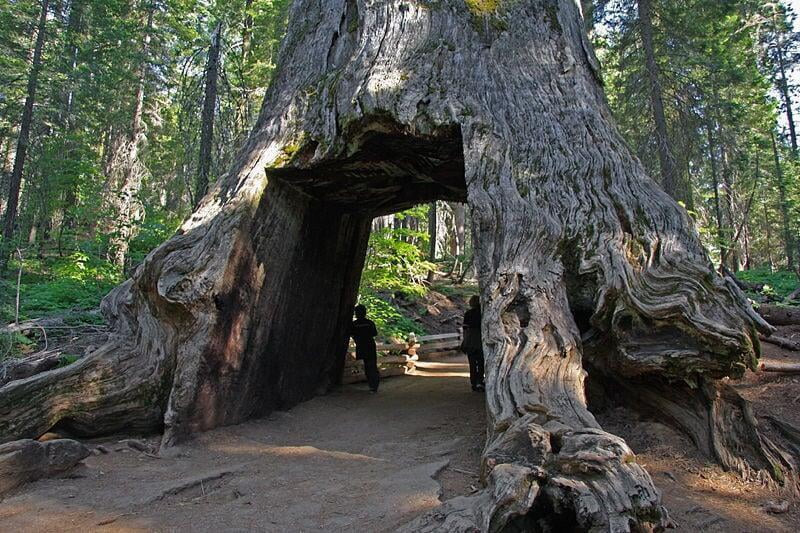

Your subject could be a unique horseshoe bend in a river, a peculiar-looking cloud in the sky, a wizened old man smoking a pipe, a towering Gothic cathedral, a snow-capped mountain, an exotic looking bird, a giant mushroom, a tribal woman wearing her traditional dress, a tattooed headhunter and countless other things.

Landscape photographs can sometimes challenge photographers with respect to identifying a clear subject, and they'll often forget the importance of having one when capturing a sweeping vista.

But this is always a mistake, as even an epic, wide-angled landscape shot needs a subject for it to be compelling, so you should always try to pinpoint specific features or elements of interest in your environment and position them in your frame.

The subject in the case of a landscape photograph might be a lake, a river confluence, a lone tree, a snow-capped mountain peak in the distance, a cool rock etc, Just remember that for it work as a standalone subject, it needs to be unusual and interesting enough to really pique the viewer's curiosity.

Indeed, a “boring” subject is hardly any better than a photo with no subject at all. The purpose of travel photography is to capture images of interesting, unusual phenomena that people living their humdrum, everyday lives don’t observe very often.

Commonplace things that people see or interact with on a regular basis or subjects that are inherently uninteresting are going to leave the same weak impression on the viewer as a photo with no subject at all.

This is what makes travel photography so exciting, as it spurs us to continually explore new frontiers in the pursuit of extraordinary and compelling new subjects to photograph.

#7 - Learn the fundamental principles of composition (and then break them)

Composition is a complex subject in photography that deserves a dedicated article all to itself, but here we’ll just cover the basic principles of good composition so that you can achieve some immediate improvement in the calibre of your images.

Firstly, what is composition in the context of photography? It’s how a photo is composed or the manner in which the elements in a scene are arranged and positioned in relation to one another and in relation to the frame of the photo.

As a photographer you don’t have complete control over the positioning of all the elements in a scene but you do have some leverage.

By varying your own position, camera angle and focal length, by waiting for dynamic elements to move into the desired position, and by rearranging the elements in a scene whose position you do have control over, you can make a dramatic difference to the compositions of your images.

We discussed the importance of having an interesting subject in your photo in tip #, but the arrangement of that main subject and any secondary elements in your frame is also critical to create a pleasing composition.

An ill-placed subject in a photo will have a jarring effect on the viewer, creating a sense of discordance and disharmony, and spoiling what could have otherwise been a great image.

The five basic principles of composition that we’re going to cover here are fill the frame, the rule of thirds, balance, straight horizons and breathing room.

Fill the frame with what you like

At any given photography location, there can be a hell of a lot going on.

For example, if you’re at the beach, there might be waves, sand dunes, sandcastles, washed-up seashells, driftwood, fishing boats, playing children, sunbathing adults, dogs, beached seals, anglers…. the list goes on.

One of most basic principles of composition can be useful here to help us figure out what we should be photographing. The principle is this: fill the frame with you like.

Decide what exactly it is that you appreciate about the scene (i.e. identify your subject) and completely fill the frame with that, to the exclusion of all the other inconsequential stuff.

Feeling excited about those beached seals? Get as close as you can to the seals without spooking them, use a zoom lens if you have to and try to fill your entire frame with them.

Don’t be the guy that takes the shot from too far away, filling most of his frame with featureless sandy beach and consequently making the seals look merely incidental and not the main subject of the photo.

Like those yellow flowers in that field?

Don’t just photograph them from a distance so that they look small and insignificant in the overall context of the image; zoom in or physically move closer so that the flowers are almost touching your camera lens and fill your entire frame with them. This will create a much more captivating photo.

Instead of doing this.....

Do this.

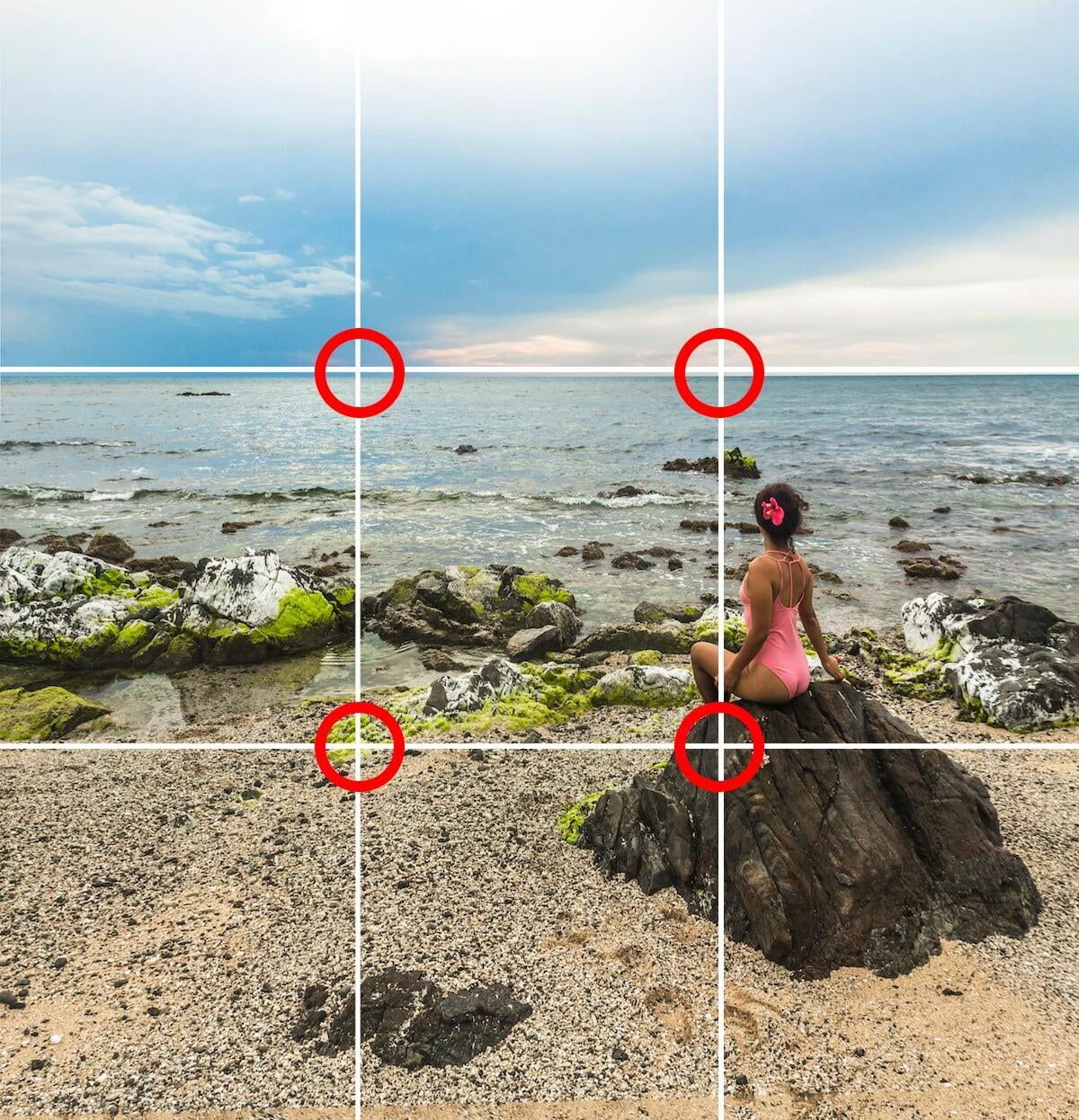

The rule of thirds

The rule of thirds is a compositional rule of thumb rather than a strict law that must always be followed. Indeed, there are plenty of occasions in photography when it can and should be broken.

Nevertheless, it’s a useful principle to bear in mind when composing your travel photos, as it works remarkably well in a great number of situations.

What is the rule of thirds?

To use the rule of thirds you have to first envision a 3 x 3 grid (like a noughts and crosses or tic-tac-toe grid) overlying the image in your frame.

This grid consists of two horizontal lines intersecting with two vertical lines at four different points, dividing the image up into nine squares of equal size.

In fact, you need not imagine these lines, as your camera probably has a grid overlay option that you can enable.

The rule of thirds uses these horizontal and vertical gridlines as guidelines for where to position your subject(s) and your horizon in the frame.

In landscape or outdoor photography, many novice photographers will instinctively position the horizon line in the middle of the image, dividing it into two equal halves, where 50% of the image is sky and the other 50% is land or water.

Although this type of composition works very well in particular circumstances (i.e. reflections, which we cover in section 3), it is a violation of the rule of thirds and typically won’t result in an appealing composition.

The rule of thirds stipulates that the horizon should be positioned on either of the two horizontal gridlines, thereby dividing the image in a 2:1 ratio of sky to land/water or vice versa.

In other words, a third of the image will consist of land/water and two thirds will consist of sky, or vice versa.

The rule of thirds also tells us exactly where we should position our subject(s) in the frame.

Like with their positioning of the horizon, novice photographers will often have a natural tendency to centre their subject in the frame, as it would seem logical to place the element of greatest importance bang smack in the middle of the frame, right on the bull’s eye.

But photography is an art and does not always follow logic, which is why positioning the subject right in the centre of an image doesn’t usually work.

Again, it’s a rule a thumb, but the rule of thirds dictates that the subject should be positioned at any of the four points in the frame where the horizontal and vertical gridlines intersect, like in the image above.

Once you've gotten comfortable with using the rule of thirds to guide your compositions, it's time to start breaking the rule and trying out different horizon and subject placements.

As you experiment, you will discover that photography is very nuanced and that blanket composition rules like the rule of thirds cannot be successfully applied to every image. The more experience you garner, the better you'll comprehend when the rule should be adhered to and when it should be broken.

Balance

The principle of balance in the context of photographic composition can get quite complicated, but we won’t delve too deeply into the subject here.

The basic idea is that a balanced photo is more appealing than an imbalanced one, as an imbalanced photo creates tension and causes the viewer to experience a desire to restore equilibrium.

When we are talking about balance in a photo, we are talking about visual balance, and we describe the elements of an image as possessing a visual weight.

In a visually balanced image, the viewer’s attention is not overwhelmingly drawn to any particular part of the image, but the entirety of the image competes for his or her attention.

There are many types of balance in a photo, such as:

Symmetrical balance

An image that is literally symmetrical (i.e. can be divided into two mirror opposites) or almost symmetrical in photography is considered to be symmetrically balanced.

Reflections can produce symmetrically balanced images, and there are lots of examples in man-made environments and monuments too, since people often endeavour to achieve symmetry in their architectural designs. Aside from reflections, symmetrically balanced images in nature are less common.

The other types of balance in an image are the various types of so-called asymmetrical balance or informal balance. These include the following:

Visual tension

If there is an element bearing considerable visual weight in the top right-hand corner of the frame, an element of similar weight can be positioned in the bottom left-hand corner to balance the image.

The objects shouldn’t be positioned literally in each corner, but roughly in accordance with the rule of thirds where the gridlines intersect.

These opposing elements can be thought of as two competing subjects that create visual tension by pulling the viewer’s eye back and forth (like a ping-pong ball) across the frame.

If an image has an obvious void or an area that looks disconcertingly empty, it is probably symmetrically imbalanced (nature abhors a vacuum), and the imbalance can be remedied by placing something of appropriate visual weight in this void.

Tonal balance

A balance between light and dark tones makes for a great image. This type of balance is particularly easy to observe in black-and-white photos but tonal balance still matters in colour photos too.

Note that dark tones carry more visual weight than light tones, so an image with a 50:50 ratio of dark to light tones is not well balanced. To create a tonally balanced image, you should aim to have more highlights than shadows.

Colour balance

Do you always ensure that the colours in your images are balanced?

If you’re shooting a lavender field for example, your photo might be overpowered by the purple of the flowers. You could try to restore balance to the image by placing a girl in a yellow dress in the scene. This would have to be planned in advance of course.

Although you might think that the purple of the lavender flowers would still dominate the image, yellow is a very bold and bright colour that carries more visual weight than the more subdued purple of the lavender flowers.

As a rule, bright and bold (vibrant) colours carry more visual weight than dull, muted colours.

Size balance

Objects with a lot of visual weight should be made smaller in order to balance them with those of less weight.

For example, the Eiffel tower carries a lot of visual weight, so if you wanted to balance that with something that’s less attention-grabbing in your foreground, you would need to shoot the tower from a distance so that it appears quite small in comparison to your foreground element.

Textural balance

Strongly textured elements carry more visual weight than smooth or textureless elements. A brick wall, for example, has a strong texture and can be used to counterbalance an eye-catching human subject.

Conceptual balance

Also known as abstract balance, conceptual balance involves the juxtaposition of abstract philosophical concepts that seem to oppose one another, like industry and nature, traditional and modern, rich and poor, fear and love, good and evil, powerful and weak, and so on.

Conceptually balanced photos are usually balanced in all the other ways too, with the addition of the underlying and opposing philosophical ideas, which may not be immediately obvious to the viewer.

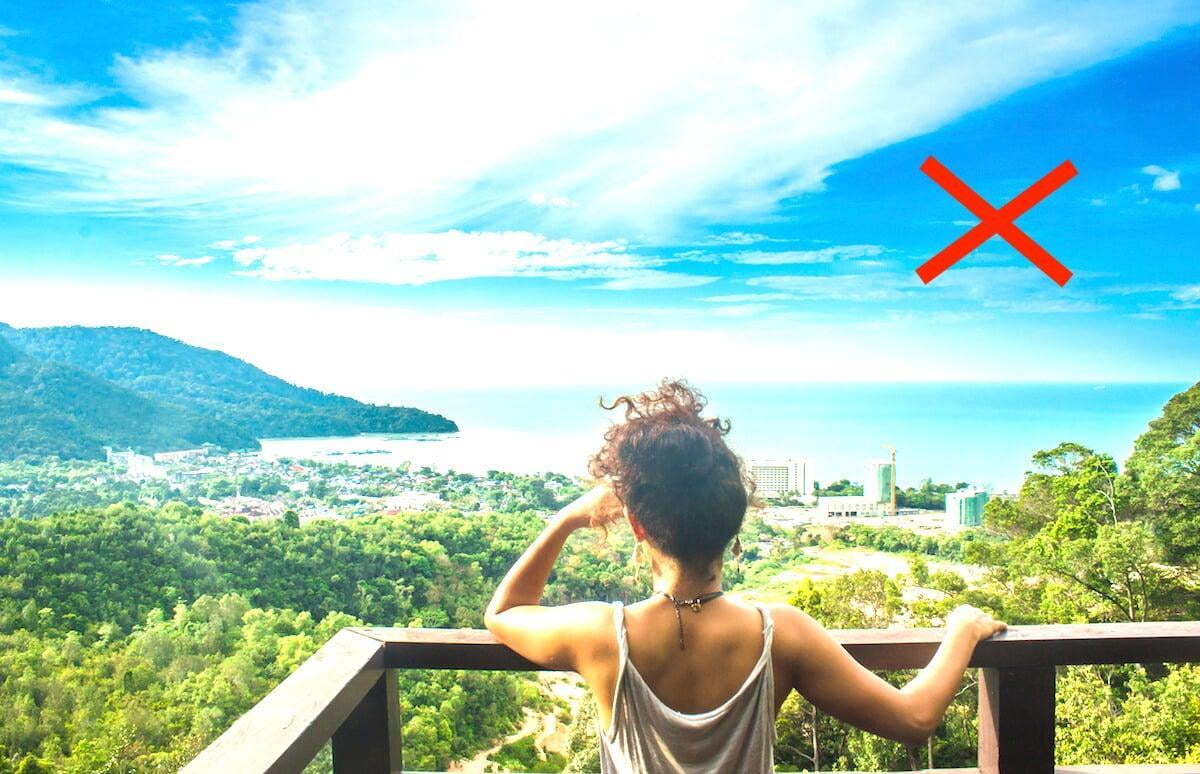

Straighten that horizon

While there are times when you might want to deliberately and dramatically tilt the horizon to create a feeling of disorientation or uneasiness in the viewer (this is known as a dutch angle, despite the fact that the technique originated in German film in the early 20th century), most photos look best when the horizon is kept perfectly straight.

Crooked or tilted horizons are a very common beginner mistake; fortunately they become less of a problem with practice. However, there's no photographer that can always take pictures with a perfectly straight horizon without some kind of technological aid.

Luckily, many modern cameras have some kind of an inbuilt electronic level that can be viewed on the LCD monitor and through the viewfinder.

The electronic level will display the angle of tilt of your camera so that you can correct it and ensure that it’s perfectly level before taking your shot.

If your camera doesn’t have this feature, you should at least be able to enable your camera’s grid overlay. By aligning one of the horizontal gridlines with the horizon, you should be able to get it perfectly straight.

However, this only works well in situations where there is a clearly visible horizon line, like when you’re looking out across the ocean at the water. There will be many situations where there won’t be a visible horizon and where your camera’s grid overlay will not help much with correcting the tilt of your camera.

If you do end up with a crooked horizon (and everyone does), it’s not the end of the world, as you can always straighten it later using the straightening tool in image editors like Photoshop.

However, you should always try to get the horizon as straight as possible in the field, as straightening it on your computer will force you to crop the image, thereby causing you to lose parts of it that you may have wanted to keep.

Leave breathing room (negative space) around elements

The elements in your image need room to breathe.

This is achieved by avoiding crowding or overlapping between the various elements in your scene, and by leaving space between elements and the edges of your frame.

By keeping the borders of your frame free of distractions, you actually create a picture frame of sorts, which helps to draw the viewer’s attention to the central areas of the photo.

Another similar mistake is when an image of a single subject (i.e. a portrait) filling the frame is too closely cropped, so that there’s virtually no space between any part of the subject and the edges of the frame. This compositional error gives an image a claustrophobic feeling, as if your subject is confined inside a tiny box.

In some situations it's also possible to make the mistake of having the breathing room on the wrong side of the subject. We might call this the rule of space.

For example, if you are photographing a subject side-on, you should leave more space in front of the subject than behind the subject. "In front" here refers to the space in the frame that the subject is either looking or moving towards.

This rule works because of our subconscious tendency to want to see what lies ahead of a subject or what a subject is looking at; we are less interested in what's going on behind the subject, so there's no reason to dedicate most of the frame to that.

While leaving breathing room is really important, but you don’t want to get too liberal with it either – there’s a balance to be achieved, as having an excessive amount of negative space in your frame could make your subject appear small or insignificant, which would violate the first rule of composition - fill the frame with what you like.

Rule of odds

The rule of odds stipulates that when there is a group of similar subjects in an image, the composition will be more visually appealing to viewers if the group has an odd number of subjects like 3, 5 or 7 rather than an even number like 2, 4 or 6.

The reason for this greater appeal may have to do with the fact that the viewer is unable to mentally divide up the group into equal-sized or symmetrical subgroups when there is an odd number of elements in it.

This means that the image maintains more cohesiveness and creates a tension, drawing the viewer in as they search for that missing element that would make the group symmetrical.

#8 - Equipment matters

Equipment is just one of a multitude of factors that contribute to the quality and impact of your travel photos, but it is nevertheless a factor of critical importance that can’t be ignored.

Just as your ability to chop down a tree would be severely hampered if you were to use a blunted axe, shooting with an inferior camera will also rob you of the ability to fulfill your highest potential in the art of travel photography.

You don’t need to have the latest, best and most expensive camera on the market to capture beautiful images, but having a decent-quality, modern camera will allow you to benefit from all the latest technological advancements.

With a good camera in your hands, you don’t have to worry that it might be your equipment that’s holding you back if your travel photos look lacklustre. When your camera gear is top-notch you can confidently place the blame on your skill level and focus on improving it.

Both the camera body and the lens that it's attached to will have a significant impact on the type and quality of the photos you will be able to take.

The lens is the primary dictator of the sharpness of your images, as it has the very important job of capturing the light from the scene in front of you and focusing it onto the sensor, which is housed inside the camera body.

The grade of the materials used in the lens, the number of glass elements, the coatings used to reduce glare and enhance colour and contrast, built-in image stabilization and other factors in the design of the lens can all impact the quality of the images it can produce.

To get the highest image quality you will need to invest in a prime lens (as opposed to a kit lens), but bear in mind that prime lenses have a fixed focal length, so if you want to make your subject bigger or smaller in the frame, you’ll have to move your feet.

The camera lens will also determine the upper and lower limits of your aperture size, which can improve your camera’s performance in low light or very bright conditions.

Prime lenses typically have a much wider maximum aperture (i.e. f/2.8 or bigger) than kit lenses, making them much more suited to shooting in low light.

The lens also determines the range of focal lengths you will be able to shoot with. If you want to be able to take ultra wide-angle or highly zoomed shots, you may want to carry extra lenses to be able to cover these more extreme focal lengths.

Bear in mind however that lenses can be heavy (especially zoom lenses) and they take up space. Additionally, the vast majority of your travel photos will probably be taken at more middling focal lengths, so those extra lenses might stay covered in cobwebs during some of your trips.

That's why carrying a whole array of lenses might be out of the question and you might instead want to carry just one extra lens when you're travelling.

It really depends on your tolerance for carrying around a lot of heavy and expensive gear when you're travelling. For me personally, I'm happy to carry one extra zoom lens when I'm on the road, but no more than that.

Bokeh, or the blurred, out-of-focus areas of an image, and how they appear, also depends on the lens you’re using. Some lenses give a more appealing bokeh effect than others, although what's "appealing" is certainly subjective to an extent.

The starburst effect is another thing that can vary considerably between lenses and some lenses don't produce a good starburst at all. We cover bokeh and starbursts in Section 3.

The camera body that you choose is also very important, as it governs many of the camera’s capabilities that the lens does not play any role in.

The sensor is housed in the camera body and this extremely important element determines the camera’s megapixel count (max resolution), its dynamic range, its noise levels, its ISO range (light sensitivity) and more.

If the camera has a full-frame sensor (vs a crop-frame sensor), it will perform much better in low-light conditions and will also have a significantly wider field of view than a crop-frame sensor for a lens with a given focal length.

There are many other important capabilities of a camera that are dictated by the body rather than the lens, like the available shooting modes, creative filters and settings, the maximum continuous shooting (burst mode) rate and the length of time it can be sustained for, the maximum and minimum shutter speeds, the battery life, the number of autofocus points, and so on.

That being said, what will make the most noticeable impact on the look of your images will be the lens that you’re using, not the camera body and when photographers are looking to upgrade, they will usually buy a new lens and keep their existing camera body.

I currently travel with the Canon EOS 77D with the EF-S 18-135 mm (f/3.5 - f/5.6) zoom lens and I’m very happy with this setup.

For a full review of this camera and of all our other top travel camera picks, see our complete guide to the best travel cameras.

#9 - Know your camera like the back of your hand (and keep it well maintained)

I’m not sure that everyone knows the back of their hand all that well, but I’m using the idiom here anyway to make the point that you ought to learn everything there is to know about your camera if you want to improve your photography.

The first rule of any trade is to know your equipment inside-out. The more you know about your camera’s functions and capabilities and when to use them, the more you’re going to be able to get out of it and the better your photos are going to be.

Start by figuring out what all the buttons, switches, dials and knobs on the outside of your camera body and lens are for.

Do you know the location and function of the depth of field preview button? What about the dioptric adjustment knob? The hot shoe? The back-button autofocus? The AE lock button?

Do you know how and when to use all the different shooting modes on your camera’s mode dial, like manual, aperture priority, shutter priority, intelligent auto mode and so on?

Many photographers who have been shooting with their cameras for years won’t even know what every single one of these external controls is for.

Once you understand what all the controls on the outside of the camera do, you can drill into the menu options and settings of the camera. If you can't figure out what a particular setting does it’s best to leave the default setting enabled.

The easiest way to learn the nuts and bolts of your camera is to consult the user manual that came with it. Although it might make for pretty dry reading, you should definitely discipline yourself to read through the manual; you’d be surprised what useful tricks and tips you might pick up there.

There are also several good YouTube channels where photographers go through the settings and controls of different cameras and explain what they do in a way that’s easy to understand. You might be able to find a tutorial for your camera model.

It’s also very important to know how to look after and maintain your camera. Again, your camera’s user manual will provide a lot of useful information here.

When you’re travelling you need to take extra care to protect your camera from rain, splashes, knocks, dust, extreme temperatures, theft and other threats to its survival.

Never leave your camera bag/case down on the floor of local buses, as I’ve travelled on buses in some countries where the patch of metal floor above the engine (near the driver) became hot enough to damage a camera, laptop or any other electronic device.

Don’t be the fool who leaves his camera unattended while mounted on an unstable tripod and then returns to witness the tripod topple over, smashing the front glass of the camera lens on the ground.

If you are changing lenses frequently, you will probably find that dust from the air will quickly get onto your camera sensor and will create dust spots in your images that can ruin them, especially if the dark spots appear in the lighter parts of the image, like the sky.

During a recent trip to Myanmar, I was shooting at one of most scenic locations in the country (the Hsinbyume pagoda in Mingun near Mandalay), but didn’t realize at the time that my camera sensor was covered in dust particulates.

When I later reviewed the images that I had taken earlier that morning, I realized to my horror that most of them were destroyed with dark spots everywhere and I had to spend ages editing out the blemishes in Photoshop afterwards.

If you face issues like this or other technical problems with your camera, you might not always be able to find somebody who can fix it or you might find (as I did) that some local camera repair shop owners are greedy and will try to rip you off.

During that same trip to Myanmar, two of the three camera repair shops in a laneway near our hotel in Mandalay were asking for exorbitant sums of money to clean our camera sensor, but the third shop was run by a kind-hearted old man with failing eyesight, who was happy to do it for free. In the end, it took the younger assistant in the shop about 60 seconds to complete the task.

In order to liberate yourself from dependency on local camera repair shops every time your sensor needs a cleaning, I recommend that you carry a basic camera cleaning kit so that you can keep your camera body, lens and sensor free of dirt, dust and fingerprints.

The bestselling cleaning kit we’ve linked to comes with a squeeze air blower (dislodges dust from the camera sensor), a soft brush (for dusting the camera body), a double-sided lens cleaning pen (removes dust and fingerprints from the lens), microfiber cloths, lens cleaning tissues and a bottle of lens cleaning fluid.

It’s very important to always remember to wipe the front glass of your lens before shooting so that there aren’t any fingerprints, dust, dirt, water droplets or condensation on it to impair the quality of your images.

If persistent condensation appears on the inside of your lens, you may be able to remove it by carefully and gently heating your lens with a hairdryer on low heat or by sitting for a while in a warm environment (i.e. a heated car) with the camera.

Just make sure that you don’t detach the lens from the camera body, as that could cause the situation to worsen.

#10 - Don't neglect to use your camera's viewfinder

If you have a DSLR camera, you may have been neglecting to use the viewfinder to compose your photographs, whether due to a lack of understanding of why this camera feature is useful or simply out of habit of using the live view all the time.

The live view feature of DSLR cameras has several advantages over the viewfinder, such as showing you the live DOF (depth of field) without having to press a DOF preview button, as well as giving you 100% frame coverage, so that you can see exactly what your final image is going to look like on screen before you press the shutter button (viewfinders often offer less than 100% coverage and crop the field of view slightly, which can mean that elements near the edges of the frame can unexpectedly appear in the final image).

Another advantage of live view is the fact that you can compose your image without holding the camera up to your face, an action which isn’t feasible in many shooting scenarios, like when shooting subjects that are close to the ground.

A third advantage of live view is the ability to use on-screen tools that often aren’t available when shooting with the viewfinder. For example, you may not be able to zoom in on your focus point or display a grid overlay, electronic level or live histogram for the scene you’re shooting when looking through the viewfinder.

But there are also occasions when using your viewfinder to compose your image is more advantageous than using the LCD monitor.

For example, on a bright sunny day you might not be able to see your LCD screen properly due to the glare, and the viewfinder would be a far better choice for composing your image.

Also, if your camera battery is running low or you’re simply not carrying any spare batteries and you want to make sure that your single battery lasts you the entire day, the viewfinder is a far better option for shooting with, as it consumes a lot less battery power than live view.

The viewfinder also works better (in my opinion) for shooting a panorama sequence, as you can keep the camera steadier by holding it against your face.

Your viewfinder may also be better for focusing, especially when there’s fast action taking place; in my camera for example, the viewfinder focusing system is a lot more sophisticated and faster at locking onto targets than the live view focusing system.

Using the viewfinder offers a more immersive experience than using live view, as you're looking directly at the actual live image of the scene, whereas with live view you're looking at an electronic representation of the scene on a screen, and you're looking at that instead of at the scene itself.

Knowing the pros and cons of each system will allow you to choose the one that’s most appropriate for the situation at end, ensuring that you always get the best possible compositions.

#11 - Learn how to shoot in manual mode

I remember I was terrible at shooting in manual mode when I first picked up a DSLR camera over 6 years ago.

All my photos were coming out overexposed, underexposed, blurry, crooked horizons, badly composed - you name the mistake, I was making it.

But by reading a few articles about how to shoot in manual mode and then putting the information into practice, I soon got the hang of it, and you’ll undoubtedly pick it up very quickly as well.

When shooting in manual mode, you decide everything; the shutter speed, the aperture size, the ISO setting, the white balance, the metering mode, the amount of exposure and so on.

With that freedom comes a lot of responsibility, but also a lot of power and control.

But why not just make life easier for yourself and use your camera’s automatic modes instead? Because you don't always get the result that you want when you let your camera choose the settings.

Shooting in manual mode gives you more control over the look and style of your photos, which means more potential to experiment and express your creativity, which is what great photography is all about.

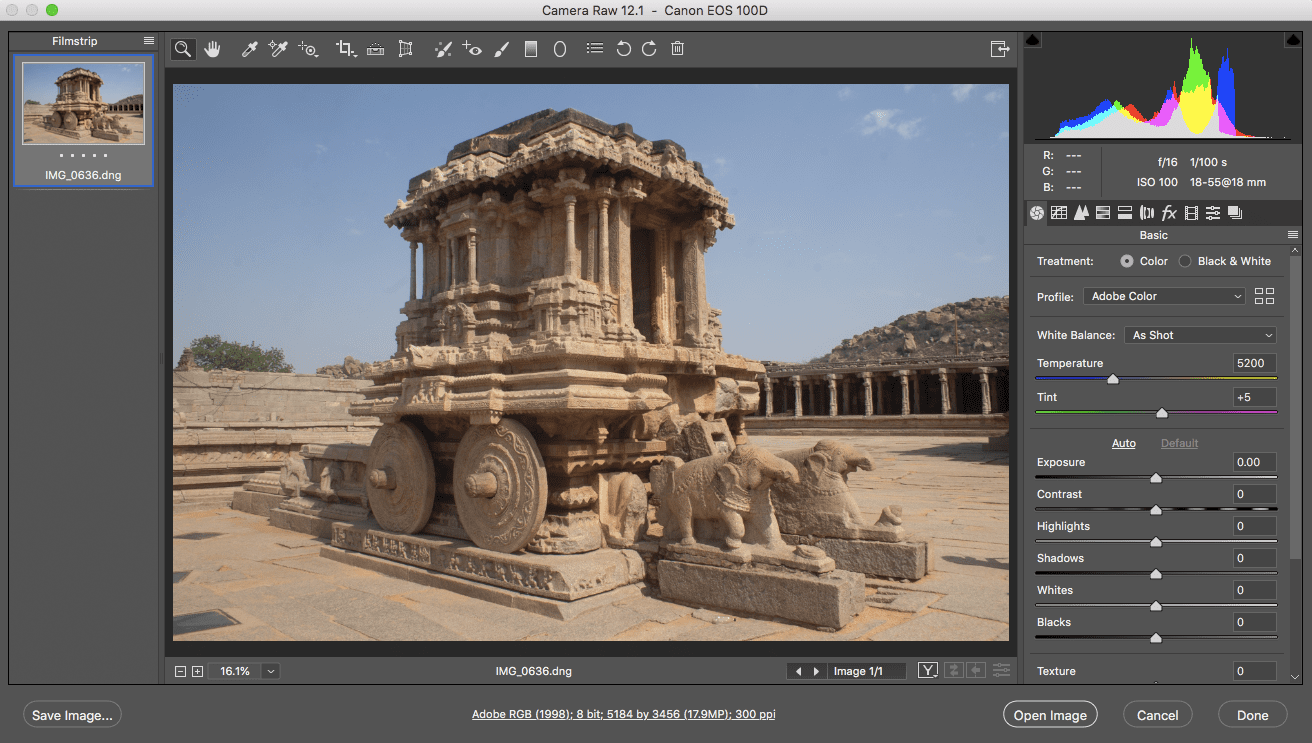

#12 - Improve the technical quality of your images

Technical quality is far from the most important factor governing the visual appeal of an image, but all other things being equal, a technically perfect image will usually be more desirable than a technically flawed one.

The aperture size, focal length, shutter speed and ISO number are all parameters that you have a degree of control over when taking a photo, and all can have a significant effect on the sharpness, noise level and other metrics that are used to assess the technical quality of the resulting image.

Regarding aperture size, most lenses have a “sweet spot” or a particular f-number that they are sharpest at. At f-numbers that are higher or lower than the sweet spot, there is a reduction in sharpness.

In the case of a lower-than-optimal f-number (wide aperture), the softening of the image is due to the reduced depth of field and also due to aberrations caused by light passing through the aperture at the edges not getting focused onto the plane of the sensor.

In the case of a higher-than-optimal f-number, the softening effect is due to the phenomenon of diffraction, where light spreads out after passing through the aperture.

The optimal f-number for sharpness is usually 2 or 3 stops down from the maximum aperture of the lens, so for a regular kit lens the sweet spot would normally be somewhere between f/8 and f/11. In practice, the easiest way to find the sweet spot for your lens is to Google it.

In practice when you’re shooting, you want to stay as close your lens’ sweet spot as you can to maximize sharpness, but there will inevitably be times when you will be forced to deviate from the sweet spot – for example, if you need more depth of field you might need to use a very small aperture or if you’re shooting in low light or you want to produce a blurred background, you may require a wider aperture.

The focal length that you choose for your shot can also have an impact on the sharpness of your images.

If you are shooting handheld, it will be more difficult to take sharp images at higher focal lengths like 150 mm, 200 mm and so on. This is primarily because the more zoomed in you are, the more that camera shake is amplified.

You can offset this effect to an extent by increasing the shutter speed but sometimes this isn’t possible and a tripod (or at least a monopod) then becomes a necessity.

Also, zoom lenses are not equally sharp across their range of focal lengths. You may find that your lens is sharpest at lower focal lengths and becomes less sharp when zoomed, although there shouldn’t be a dramatic difference in this regard.

The ISO number is always best kept as low as possible when the goal is to produce sharp images, as the higher the ISO, the more noise (those multi-coloured specks that mostly occur in the shadow areas of an image) that’s introduced into the image, and noise always reduces the quality of an image.

This is why it’s very important to carry a tripod, as it means that you don’t have to jack up the ISO number (or at least not as much) in low-light situations in order to obtain a sufficiently exposed image.

Selecting the appropriate shutter speed for the circumstances is also crucial for a technically sound image.