The Complete Guide To Visiting Stong Waterfall: The Tallest Cascade In Southeast Asia That Most Travellers Miss

Here we were, seated comfortably in an almost passenger-less, air-conditioned carriage, as our train trundled along the tracks through the Malaysian countryside.

As we gazed out through the slightly grubby windowpanes, a delightful array of different scenes and landscapes flashed before our eyes.

The train rattled past palm oil plantations, rubber plantations, lush green meadows, soaring limestone outcrops and tiny forgotten villages. We glided across impressive railway bridges spanning wide mud-stained rivers and cut swathes through pockets of thick jungle forest.

We were aboard the jungle train, which serves Malaysia’s east-coast line, better known perhaps as the jungle railway.

The term “east-coast line” is something of a misnomer however, as it only goes near the coast at its terminus in Tumpat right up in the extreme northeastern corner of Malaysia. In fact, most of this railway line winds through the country’s remote interior regions.

We had each bought a one-way ticket earlier that morning at the railway station in Wakaf Bharu, a small town tucked away in the northeastern corner of Malaysia and only one station away from the terminus in Tumpat.

Our point of disembarkation? A tiny village in the middle of nowhere called Dabong, where there’s a railway station, a mosque, a restaurant, a few houses and a single guesthouse called “Rose House” that is aptly painted red.

There are also a number of limestone caves near Dabong, including Gua Ikan, Gua Kris, Gua Pagar and Gua Pelap. The caves are said to be 225-million years old and are inhabited by bats, rare endemic flora and other darkness dwellers.

Most of the caves are easy to access but are tricky to locate without a guide. All are said to be in good condition except for Gua Ikan, which is covered with graffiti. You can learn more about the caves on this page.

We however had not come here to see the village or the caves. No, the real reason we had stopped here was to see the spectacular Jelawang waterfall in the nearby Gunung Stong State Park (GSSP).

Gunung Stong State Park (GSSP)

Formerly known as Jelawang jungle, the park was gazetted as the Gunung Stong State Park (GSSP) in 2007 and is named after the prominent peak of Gunung Stong (1,422 m), a mountain that is found inside the park.

The park is currently maintained by the Kelantan State Forestry Department.

The terrain of GSSP is rugged and heavily forested with tree cover extending into the higher elevations of the park, meaning that some of the peaks do not offer much of a view.

The dominant rock type is migmatite, which consists of a mixture of metamorphic rock and igneous rock. It forms when a metamorphic rock partially melts and the melted portion then recrystallizes into igneous rock, creating a new hybrid rock with interesting textures and banded colours.

The jungle here supports a rich diversity of flora and fauna, although animals are usually difficult to see.

There have been sightings of Asian elephants, Malayan tigers (Panthera tigris jacksoni), black panthers (Panthera pardus), seladang (Bos gaurus), Malayan tapir (Tapirus indicus), serow (Capricornis sumatraensis), Malayan sun bear (Helarctos malayanus), barking deer (Muntiacus muntjac peninsulae) and several other species.

Over 130 species of birds have been recorded in the park, including five different species of hornbill. The beautiful great argus pheasant (Argusianus argus) with its spectacular tail plumage can be spotted here too.

Two interesting endemic plant species found in the park are the small bamboo (Holttumochloa pubescens) and a type of fan palm (Licuala stongensis).

The biggest attraction for most people that come here is the seven-tiered, 305 metre-high Jelawang waterfall (also known as Stong waterfall).

Beginning at an elevation of 460 m above sea level, the river tumbles down a colossal slab of exposed bedrock, which appears as a huge birthmark on the landscape from afar.

In fact, this mass of exposed rock is so prominent that you can see it from several kilometres away, most notably during the journey from Dabong to Jelawang village.

According to a sign near the park entrance, the Jelawang waterfall is just one of seven waterfalls found in the park. It is no doubt however, the largest and most awe-inspiring of all of these.

A popular activity among Malaysian hikers and backpackers is to hike up to the top of the waterfall, stay overnight in the established campsite there by the river and then rise early in order to witness the first rays of the morning sun breach the horizon from the vantage point at the edge of the waterfall.

This vantage point at the top of the Jelawang waterfall, as you will soon see, makes one feel as if one is standing at the edge of the Earth itself.

The campsite at the top is called Camp Baha and lies at an elevation of about 460 m above sea level.

The campsite is named after a former local guide who died in 2002 and who established most of the trails in the park. There are kitchen facilities here and you can rent a hut for around 10RM. You may be able to borrow a sleeping bag here from one of the forest rangers but you shouldn't count on it.

Many people also use the campsite as a base for hiking out to various peaks found inside the park but beware, there are jungle rats about so make sure to hang your food from the ceiling if you decide to stay overnight.

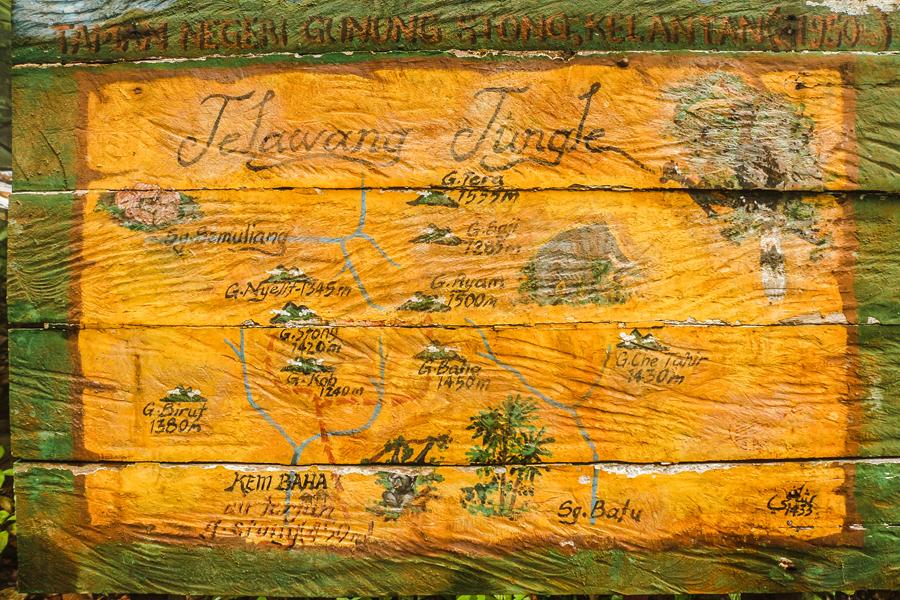

Painted on a wooden sign in camp Baha, there is a rustic looking map that displays the names and rough locations of 8 different peaks found inside the park:

The three most accessible and most commonly climbed of these are Gunung Stong (1,422 m), the two most accessible peaks in the park are Gunung Ayam (1,504 m) and Gunung Baha (1,309 m).

Gunung Ayam reportedly offers the best views and is about 5-8 hours from camp Baha.

Gunung Tera (1,555 m) and Gunung Che Tahir (1,430 m) require a 3-4 day trek through the jungle to reach and you’d probably want to hire a guide if you plan to tackle them.

Highly adventurous travellers may be interested in taking on Mr. Baha’s seven-summit challenge, which takes on seven of the park’s peaks during a 7-day long trek. It would be best to hire a guide if you’re going to do this.

Location

The entrance to Gunung Stong state park is about 1km from the diminutive Jelawang village and is reached by taking a turn-off from the main road just 500 metres outside the village.

Dabong is the nearest railhead to the park and is located about 6km northeast of Jelawang. It lies at the confluence of the Sungai Galas and Sungai Pergau rivers.

Getting there

By train:

The best way to get to GSSP is to first take the train to Dabong. Seeing that Dabong is on the jungle railway line, you can reach it from any of the other train stations on this line.

A one-way ticket from Wakaf Bharu train station (near Kota Bharu) cost us just 5 RM each. If coming from Kuala Lumpur, you’ll have to ride the main line south until you reach Gemas, where you can change trains and get onto the jungle railway line to head north for Dabong.

By boat:

If you happen to be in Kuala Krai, you may be able to take a boat up the Sungai Galas river all the way to Dabong. The boat ride supposedly takes 1 hour. You will have to make enquiries about this locally.

If you don’t want to hitchhike, you can try paying some local to bring you, either from Dabong or from the bridge, which should cost you around 15RM.

Getting to GSSP from Dabong:

From Dabong, you have to first get to Jelawang village. Hitchhiking works well if you wait just before the bridge that crosses the Sungai Galas river. We rarely had to wait longer than 20 minutes for a ride.

It’s about a 10-minute walk to the bridge from Dabong. If you don’t want to hitchhike, ask around in Dabong for a taxi. You can also catch a motorcycle or other taxi from the bridge.

When you reach Jelawang village, it’s only 1.2 km or so to the entrance to Gunung State Park.

You have to first turn off the main road onto a minor road and then turn off that minor road where you see a sign for the park. The walk to the park entrance is actually quite enjoyable as there are some fabulous views of the waterfall on the way in.

Where to stay

If you want to stay as close as possible to the park, then you will want to stay in Jelawang village. It may also be possible to stay in one of the cabins just inside the park entrance but during our visit, these were all undergoing renovation and were too dilapidated to accommodate anybody.

In Jelawang we found three homestays, but we only inspected the one that’s located on the main road beyond the turn-off for the park. It was clean and looked comfortable, although the asking price was too high for our budget – 80RM. You can probably forget Wifi in any of the homestays in Jelawang.

We later spoke to a local woman back at the village who also claimed she had a homestay. She offered us a price of 40RM after some haggling, which is about the best price you’ll be able to find here in Jelawang.

If you’re willing to stay a little further afield, you can stay in Dabong, at the Rose House guesthouse, which is what we decided to do in the end.

The owner charged us 90RM for 2 nights but if you’re only going to stay one night you may have to fork out 50-60 RM. The room had AC, a fan, an attached bathroom, a kettle and was very clean. There was no Wi-Fi however.

A lady also showed us another guesthouse in Dabong, but it wasn’t operational at the time. However, according to reports that we read online, people have managed to stay here in the past.

How to hire a guide

A guide isn’t necessary if you just plan to hike to the top of the waterfall. The trail to camp Baha is well travelled and easy to follow.

However, if you plan to hike deeper into the park to summit any of the peaks, you may want to take a guide. We can’t say for sure if one is necessary because we didn’t hike to any of the peaks.

Our normally reliable offline maps app (maps.me) didn’t have any data on the trails in the park, so it might be difficult for you to find your way with technology if you were to go it alone.

If you want to hire a guide, your best bet is probably to go to the park entrance and speak to the people there.

When we hitchhiked to Jelawang on the day of our arrival, the gentleman that gave us the lift actually brought us to the park entrance to try to find us a guide, assuming that we wanted to hire one without even consulting us.

Our journey to the top of Jelawang waterfall

We arose early in morning at about 7 a.m and made our way on foot from our guesthouse to the bridge crossing over the Sungai Galas river. It was not long after sunrise and the world was still bathed in a dim blue light.

We had been a little concerned that there’d be a dearth of traffic at this hour of morning and it turned out that we had been right.

A ghostly silence hung over the roads and we half-expected to see tumbleweed rolling past us as we stood there at the bridge.

We had no choice but to begin walking towards Jelawang and hope that a vehicle would eventually come and offer us a free ride.

So we set out on foot towards Jelawang and sure enough, we were both soon sat in the back of a car with two local Malays seated in front.

We made some small talk with them before they dropped us off in Jelawang village. From there, we made our way to the turn-off for the park and from there we began the pleasant 15-minute walk towards the park entrance.

As we mentioned previously, the 15-minute walk from the turn-off to the park entrance is worthwhile in itself. It lets the anticipation slowly build and affords some spectacular views of the waterfall from afar.

Even at this distance, the waterfall is an imposing and majestic feature of the landscape, an eye-catching anomaly, standing out like a sore thumb from the endless green of the surrounding jungle.

As we neared the park entrance, we admired how the golden rays of the morning sun were illuminating the waterfall and upper tiers of the jungle, while the rest of the landscape was still bathed in that gloomy blue morning light.

The park entrance itself is nothing grandiose or boastful; it simply exists to mark the boundary between the realm of man and the realm of nature.

Once inside the gate, there was apparently no entrance fee to be paid and we began walking up a gentle slope, following a trail that leads towards the foot of the waterfall.

On our way we passed by several dilapidated-looking wooden cabins raised on concrete stilts. These belong to the now decrepit Gunung Stong State Park Resort and are not fit for rats, let alone human beings.

Indeed we had enquired the previous day about the possibility of staying in these cabins but we were told that they were currently undergoing renovation.

After a few minutes, the trail brings you to a suspension bridge spanning the river to your right hand side. At this point you have two options; you can remain on this side of the river and continue hiking uphill along trail (a) or you can cross the bridge to the other side and begin hiking up along trail (b).

Trail (a)

There are many man-made concrete steps on trail (a) and it hugs the river quite tightly as it ascends. After you’ve gained quite a bit of ground, there’s an opportunity to walk out onto the bedrock of the river itself and witness the most impressive cascade of the entire waterfall. It’s basically a huge waterslide tumbling down a bare rock face and it makes for a spectacular photograph.

When we were stood here a group of Malaysian hikers stepped out onto the rocky riverbed in front of us to take some selfies.

At one point somebody managed to drop a phone and it started bouncing down the rock face before falling into a small water-filled crevice. One of the boys in the group climbed down into the crevice and managed to retrieve the waterlogged phone. What a miracle it would be if that phone ever works again!

Now if you want to continue on to camp Baha from here, we’ve read that you must cross over to the far side of the river and ultimately try to rejoin the other trail (b) on the far side. We actually came here after we had already gone up and come back down trail (b) so we didn’t do it this way.

Trail (b)

When we first reached the junction, we opted to cross the suspension bridge and take trail (b) because it’s always fun to traverse a rickety wooden bridge and we were in no hurry to reach the top.

.jpg)

From the middle of the bridge, there’s a nice view of the lowermost tier of the waterfall, but this is nothing compared to the dramatic cascade visible from trail (a).

After crossing the bridge to the other side of the river, the real hiking now begins. You’re now on a proper jungle trail, ascending steeply alongside the river. It’s quite an arduous and challenging hike, especially with the heat and high humidity. Exposed tree roots cross the path in many places, often acting as natural steps and handholds.

Some stretches of the trail consist of a slick mud slope, with man-made footholds in the mud to help prevent you from slipping and sliding. The high levels of foot traffic from weekenders have worn away all the ground cover on these stretches. We didn’t have any problems with leeches on this trail thankfully.

After a while the trail starts to curve the right, heading away from the river. You’ll know this has happened when you can no longer hear the sound of the water. Don’t worry though because the trail eventually curves back to the left, bringing you back to the river.

Before you reach the river, you’ll come to a T-junction and a signpost. Don’t turn right off the trail here at this junction, unless you’re planning to hike up to Gunung Stong. It’s another 3-4 hours of uphill walking to the peak and the view is nothing to write home about, so be forewarned.

If you continue on straight you’ll end up at Camp Baha, which is right next to the river. You’re now at the top of the Jelawang waterfall.

.jpg)

When we reached camp Baha, it was completely deserted. A thick fog filled the jungle in the cool morning air, creating an eerie atmosphere. All the overnighters were apparently still fast asleep inside their tents and cabins.

We soon found a trail leading down to the river, stripped down to our underwear and plunged our overheated bodies into one of its welcoming rock pools. We immediately breathed a sigh of great relief.

The chilled mountain water was immensely therapeutic after the hot, sweaty, energy-depleting hike. It cooled our bodies to the core, soothed our aching muscles and joints and replenished us. It was a testament to the extraordinary healing power of water.

We continued to play in the rock pools for half an hour or so, dunking our heads beneath the foaming mini-waterfalls and trying to swim upstream against the current. The riverbed consisted of smooth bare rock as opposed to sand or gravel and was a little slippery to walk on but manageable enough.

After a while, we began to actually feel a little cold and had had our fill of the whole cooling-down-in-the-river experience. We climbed out of the river, dried ourselves off, put our clothes back on and decided on where to go next. The morning fog still hadn’t lifted so it was still pointless to go to the edge of the waterfall, as there would be no view.

We thus decided to instead head upstream alongside the river, passing through the campsite on our way. It was then that we saw a curtain of falling water through a gap in the trees ahead of us. This was a scene straight out of a fairytale. Feeling incredibly excited, we rushed towards it to investigate.

Indeed, there is another waterfall just upstream of camp Baha. We’re not sure if it has a name, but it is a really beautiful one. In fact, it’s more of a waterslide than a waterfall; a sloping slab of rock that the river tumbles down, forming beautiful geometric patterns as it does so.

.jpg)

Some of the campers had left their makeshift fishing rods on the rocks here overnight and some sandwich bags were hanging from a tree, filled with white bread to use as bait for the fish.

The rods were a very simple affair, with a length of fishing line tied to the end and a weight and fishhook tied to the end of the line. We gathered that they were made from the stems of a locally common species of palm tree that the boys had removed the prickly spines from. Borrowing a rod, we tried our luck fishing in the deep and mysterious rock pools below the waterfall but it wasn’t our lucky day apparently.

After this, we went back to the campsite and decided it was time to make our way to the edge of the waterfall. Some of the campers had now woken up and were going about their morning chores.

After first heading down a narrow trail to the river, we carefully made our way out onto the bare rock, which was pockmarked with water-filled potholes in many places. We then sat down on the rock and waited patiently for the mist to clear.

At this time the river was low and was only cascading down the extreme right hand-side of the waterfall in a narrow torrent, leaving the majority of the bedrock completely dry except for a few water-filled potholes. We still had to be cautious not to go too close to the edge however.

There have been one or two mishaps here, including one in 2013, where a 23 year-old undergraduate studying at the National University of Singpore (NUS) fell to his death while enjoying the sunrise from the brink of the waterfall. Had it been the monsoon season, flash floods would have been another major concern.

It was becoming warmer now as noon was approaching and the mist was slowly beginning to clear, affording us a few brief and tantalizing glimpses of the landscape below before it would roll in again and obscure the view. Eventually, the mist vanished completely, never to return, leaving us with an awe-inspiring view of the landscape below.

This was the peak moment, the highlight of the whole experience. There we were sat, perched at the brink of the highest waterfall in Southeast Asia, taking in the glorious view as torrents of water tumbled down the inclined rock face just metres away from us.

Incredible moments like these remind you why you go through all the hardship and struggle of the climb in the first place. It’s always worth the trouble in the end for that one moment of glory and the memories that you create will last you a lifetime.

If you liked this travel guide or found it useful, please share it with other travellers. Why do you think that the highest waterfall in Southeast Asia has completely passed under the radar of so many western travellers? Leave us a comment below.

JOIN OUR LIST

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

ABOUT US

Our names are Eoghan and Jili and we hail from Ireland and India respectively.

We are two ardent shoestring budget adventure travellers and have been travelling throughout Asia continuously for the past few years.

Having accrued such a wealth of stories and knowledge from our extraordinary and transformative journey, our mission is now to share everything we've experienced and all of the lessons we've learned with our readers.

Do make sure to subscribe above in order to receive our free e-mail updates and exclusive travel tips & hints. If you would like to learn more about our story, philosophy and mission, please visit our about page.

Never stop travelling!

FOLLOW US ON FACEBOOK

FOLLOW US ON PINTEREST

-lw-scaled.png.png)