The Ultimate Guide to Visiting The Mysterious Plain of Jars in Phonsavan, Laos

We were here. We had finally made it to the town of Phonsavan, the capital of Xieng Khouang Province in northeastern Laos.

After boarding a bus late in the evening from the Phoukhoun junction at the intersection of highway 13 and highway 7, the vehicle careened along the latter artery, barrelling along the twisting road in the dead of night for 135km, before the driver finally dropped us off on the main drag in Phonsavan later that same night.

Xieng Khouang province has a great deal to offer travellers, but our principal reason for coming here was to explore the mysterious plain of jars, an archaeological landscape of rolling hills and grassy meadows, across which thousands of enigmatic 2,000 year-old megalithic stone jars lie scattered.

Location

The plain of jars is located in Xieng Khouang province in northeastern Laos, which is a province that occupies the Xieng Khouang plateau, an upland area of rolling hills and meadows, with an altitude that averages 1,300 metres above sea level.

The closest town to the accessible jar sites is Phonsavan, the provincial capital. Phonsavan lies at about 1,100 metres above sea level and is the ideal base for seeing the plain of jars. It’s located about 389km from Vientiane and 263km from Luang Prabang.

Getting to Phonsavan

By air:

Phonsavan has an airport (Code: XKH), located about 5km south of town on the road out to the plain of jars. Lao airlines has several flights each week between Vientiane and Phonsavan.

By bus:

There are daily buses to Phonsavan from Vang Vieng, Luang Prabang and Vientiane.

Vientiane: You can take a local bus or VIP bus from the northern bus terminal. The 389 km journey takes about 10-12 hours.

Luang Prabang: Local buses leave from the southern bus terminal in Luang Prabang and the 263km journey takes about 8 hours.

Vang Vieng:Local buses leave from the main bus terminal Vang Vieng and the 234km journey takes about 7-8 hours.

By minivan:

You can also hire minivans from Luang Prabang and Vientiane to Phonsavan.

If you get stranded at the Phoukhoun junction between Highway 13 and Highway 7 and as we did, just wait until the evening and there should be a bus coming from Vientiane and going to Phonsavan that you can board.

The origin and purpose of the stone jars

Material from the plain of jars has been dated all the way back to 2000BC, making the plain of jars over 4000 years old but with finds from the iron age (500BC - 500AD) dominating the archaeological records. It's clear that the plain of jars has spanned a very long time period in history.

However, very little is known about the actual people or the civilization that created the stone jars.

It’s believed the jar sites may lie on what may have been an ancient trade route that linked the Mekong river basin to the southwest with the Gulf of Tonkin to the northeast.

The people of the plain of jars may have sought commodities like salt and might have traded minerals for it, since the plains are rich in iron ore and other metallic minerals.

There may also be a connection between the jars found here in Xieng Khouang province and similar funerary urns found in the North Cachar hills of Assam state in India.

A connection may also exist between the jars and the mysterious stone megaliths or menhirs of Hua Phan province, found off Route 6 on the way north to Sam Neua.

But the million dollar question is, what were the jars used for? What great need motivated the people to painstakingly carve out thousands of these stone jars from solid rock?

Unfortunately, the original purpose of the jars is still something of an unsolved archaeological mystery. Today they litter the hillsides and meadows around Phonsavan, collecting rainwater and cobwebs and refusing to give up their secrets.

There are of course a few theories floating around that attempt to explain the original purpose of the jars including:

The ‘distilling vessels’ theory:

This is the theory that’s the most widely accepted by archaeologists and no; it has nothing to do with alcohol brewing.

The theory supposes that the jars were used to first decompose and dry out the dead corpses, before the remains were removed several weeks or months later to be cremated or possibly to be given a secondary burial in a gravesite near the jars. It's believed the jars were also used to store the ashes and belongings of the cremated individuals.

Even today, this practice of ‘distilling’ the bodies before cremation is followed by Laos, Cambodian and Thai royalty. The final cremation can take place months after the time of death. It’s believed that the practice gives the souls a chance to make the transition from the earthly to the spiritual world.

French archaeologists began puzzling over the mysterious jars in the early part of the 20th century and they collected some evidence to support this theory.

In 1923, Henri Parmentier found various objects inside some of the jars, including hand axes, jewellery, glass and carnelian beads, bronze bells and other items. However, many of the jars had already been plundered for treasures before his arrival, so who knows what else he may have found.

A few years later, french geologist and amateur archaeologist Madeleine

Colani carried out 3 years of research on the jars and produced a 719-page, two-volume tome called 'Les mégaliths du Haut laos' (The megaliths of upper Laos) that's only available in French.

Colani discovered bone fragments, teeth and glass beads embedded within black organic soil inside some of the jars. Some jars contained remains of more than one person.

She also found burial sites around the jars containing human bones, pottery fragments, iron and bronze objects, glass and stone beads, ceramic weights and charcoal.

Now the interesting thing was that the bones and teeth inside the jars showed signs of cremation, whereas the bones she found in the burial sites around the jars had not been burned. Also, the evidence suggested that the cremated remains inside the jars mostly belonged to adolescents.

The evidence would suggest that not everybody was cremated and that those who were cremated ended up inside the jars. But why did the cremated material belong mostly to adolescents? Was this practice reserved for those that died prematurely? There are many unanswered questions.

The uses of the jars may also have changed over time. The archaeologists still don't enough evidence and information to fully explain all the different findings and research has been hampered by the danger posed by all the unexploded ordinance lying around (see recent history below).

The rainwater collection theory:

One interesting theory is that the jars were used to collect seasonal monsoon rainwater for the travelling traders. Water would have been scarce along the route at certain times of year and the traders could set up camp near the jars and boil the stagnant water to render it potable again.

They may have left beads and other valuable objects inside the jars as a kind of ritual offering of thankfulness for the life-giving water.

The local legend:

One local legend tells of a cruel chieftain called Chao Angka that ruled the area in the 6th cenury. He oppressed his people so terribly that they appealed to a good king of the North called Khun Jeuam to liberate them.

A battle ensued and the army of Khun Jeuam was victorious. He then had the jars constructed to ferment and hold rice wine during a celebration that lasted several months.

The recent history

If you’re not familiar with the history, the entire country of Laos was heavily bombed by the U.S from 1964 to 1973, during an operation known as the secret war on Laos. The U.S were supporting the Royal Lao Government against the Pathet Lao communist forces and trying to interdict traffic along the Ho Chi Minh trail.

Over 2 million tons of ordinance was dropped on Laos during 580,000 bombing missions, equivalent to an entire planeload of bombs getting dumped every 8 minutes, 24 hours a day for 9 years; more bombs than all the bombs dropped on Europe during world war II. This makes Laos the most heavily bombed country per capita in history.

The problem is, that of all the bombs that were dropped, about one third never exploded. In fact, since the war ended in 1973 more than 20,000 locals and villagers have been killed or injured due to the unexploded ordinance.

A lot of the bombs that were dropped were cluster bombs, which break apart before impact, releasing hundreds of smaller bomblets. The invididual bomblets then spray ball bearings in all directions when detonated. The big problem is that around 80 million of these didn't explode.

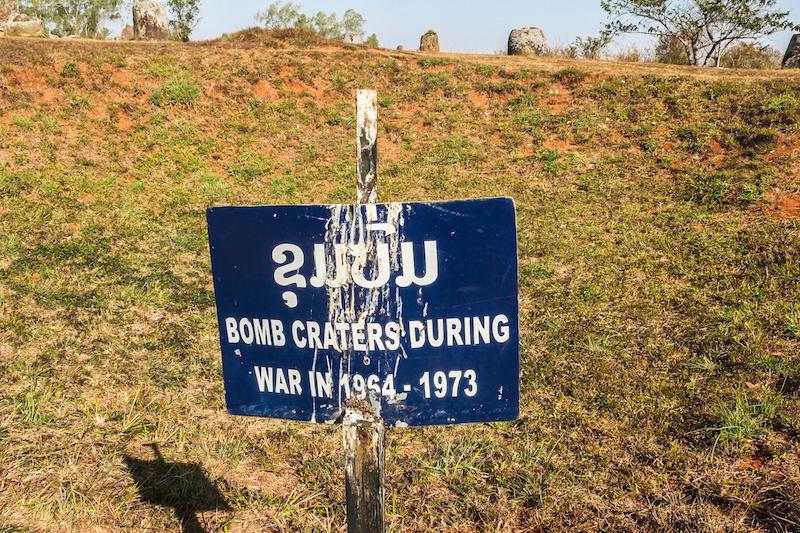

Xieng Khouang province was hit hard by the bombings. Not only is the area around Phonsavan called the plain of jars but it is also called the plain of scars.

Bomb craters are found all over the place and some of them are truly enormous. You can see displays of old bombshells outside houses and restaurants in Phonsavan town and in Ban Tajok village, bomb shells have been incorporated in the construction of stilt huts.

Villagers also try recycle scrap metal from the bombshells, which they’ll either sell to Vietnamese traders or craft into souvenirs. For example, metal souvenir spoons can be found in Ban Napia village that are crafted from melted down bomb scrap metal.

Collecting the scrap metal is an extremely risky business however and many villagers lose their lives in the process when the bombs explode. The bomblets are also a major hazard to young children, who often mistake the cluster bombs embedded in the soil for balls or even local fruits.

Bomb craters can even be found at many of the jar sites and some of the jars show evidence of having been damaged and split open by the violent bomb explosions.

Many of the jar sites acted as strategic high points for mounting anti-aircraft machine guns during the war and some jars can even be found that are pockmarked with bullet holes. You can even find war trenches dug at several jar sites.

You do have to be careful not to venture too far from the cleared areas as you explore the jar sites, as there is still unexploded bombs and landmines lying around.

Stay within the safety markers left by MAG (you'll spot these small square-shaped markers on the ground) and you should be safe. The white side of the markers indicates the safe side, whereas the red side of the markers indicates an area that has yet to be checked for bombs and landmines.

.jpeg)

An overview of the plain of jars

Although collectors have taken away some of the smaller ones, thousands of stone jars remain scattered across the plains of the Xieng Khouang plateau, mostly to the southwest and northeast of Phonsavan.

The jars are not distributed haphazardly but rather found in clusters at numerous jar sites, with each site having anywhere between 1 and 400 jars. In total, about 85 different jar sites have been discovered to date.

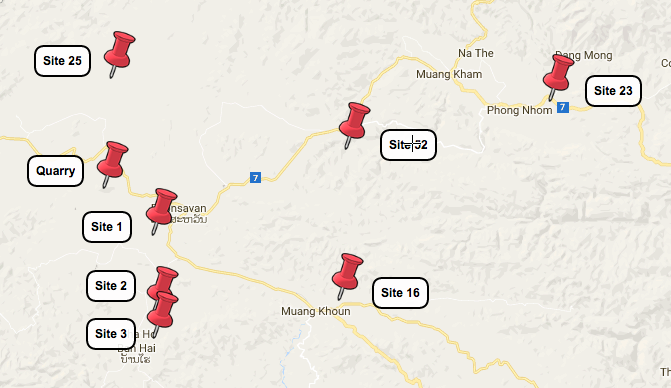

Of all the existing jar sites, only 7 sites are accessible to the public. You can only access site 1, site 2, site 3, site 16, site 23, site 25 and site 72.

The reason for this is because of dangerous unexploded ordinance (UXO) that hasn’t yet been cleared by the organization in charge, which is MAG (Mines advisory group) and they have a visitor information centre in Phonsavan.

Site 1, Site 2 and Site 3 are the three most visited sites and all are considered reasonably free of UXO. They lie almost along the same line running south from Phonsavan.

For the rest of this article, we will deal with our experience exploring these 3 sites and see what they have to teach us about the jars.

Exploring the plain of jars

During our stay in Phonsavan, we visited 3 out of the 7 accessible sites; Site 1, Site 2 and Site 3. We also visited some of the jar quarry sites on Phou Keng mountain.

Site 1 - Thong Hai Hin

.jpg)

Site 1 Layout

Site 1 is the most accessible and the most studied jar site. We found it to be the most impressive of all the sites we visited. It’s located about 9.5km from Phonsavan market.

To get there, take highway 1D south for about 5km and then take the right turn that brings you to the site after another 2.5km or so.

The site covers an area of 25 hectares and there are 334 jars in total, divided into two main areas. The ticket booth is on your left as you approach but it can be avoided if you don’t want to buy a ticket. There is a path leading off to the left and heading towards the top of a small hill, which you can take before you reach the ticket booth.

This was the path we first took and it leads up to the top of a small windswept hilltop:

From the top of this hill there are fine views of the jars below to the west and north. Even though the map claims that this hilltop is a dead end, we found a trail down to the jar sites from here. It’s also possible to skirt around the hill entirely to the south and reach the jars that way.

On the northwest side of this hill, there is a small limestone cave which you can enter and explore inside:

The cave has become a Buddhist shrine for the local people and they leave incense, cigarettes and money donations inside. Others locals sometimes enter and pocket some of the cash that’s left there.

Moving inside the cave, you’ll notice numerous miniature stupas built from local rocks by the entrance on the left hand side:

There are two man-made holes in the ceiling of this cave, although the picture on the left only shows the one directly above the main shrine.

When Madeleine Colani investigated the cave in the 1930s, she found the walls to be heavily blackened by smoke and speculated that these holes were man-made chimneys and that the cave was used as a centralized crematorium for burning the bodies of the dead.

Leaving the cave behind and heading out to see the jars, you’ll observe that there are two major groups of jars.

The first group runs in a long curving arc from north to south, starting just to the northwest of the cave entrance:

The jars are not in isolation but rather are associated with gravesites. You’ll notice several quartz stones lying around near the jars. These are believed to act as some kind of grave-markers.

You'll notice the jars here come in many different sizes and this is true for all the jar sites. The majority of the jars range between 1-2.5 metres in diameter & height and the weight of each jar ranges between 500kg and 6 tonnes.

Because the jars were extremely heavy, it’s believed that most of the boulders that the jars were carved from were sourced from adjacent quarry sites.

Many jars may even have been carved in situ, from boulders that already lay in the desired position. This would help to explain why the dimensions of the jars are so variable (i.e they didn't get to choose the size of the boulder).

Other boulders and half-finished jars were transported from further afield. In fact, many of the jars from this site are believed to have originally come from quarry sites on the slopes of Phu Keng mountain, which we’ll show you later in the article.

But how did they transport these half-finished jars from so far away and bring them up to such elevated locations? The answer may be that they exploited the strength of elephants. Thousands of years ago, Laos was the land of a million elephants.

The shape of the jars is interesting, with a wider base that tapers slightly to the top.

Most of the jars have enough internal volume to conceal a small person inside (don't ask us how we know this) although some unusual jars in Phukoot district (Site 25) have a very small internal space with extremely thick walls.

Virtually all the jars are plain and undecorated except for a select few and one of those rare decorated jars is found here at site 1 (jar no.217). It has a carved bas-relief in the form of an anthropomorphic figure; we didn’t find this unfortunately. There’s also said to be a very curious zoomorphic carving on one of the jars at site 2. There may be more carvings that have yet to be discovered.

5 types of rocks have been used to construct the jars, including sandstone, limestone breccia, conglomerate, granite and limestone but sandstone is the most common material, possibly either due to its abundance or ease of working.

Here at Site 1, two of the five rock types are found; sandstone and conglomerate. Sometimes villagers use the sandstone jars for sharpening their knives and some jars can be found with deep grooves that have formed from this activity (you can find a jar with such a groove at site 17).

There are several bomb craters scattered around Site 1. They’re mostly just large, circular grassy depressions in the ground. Some of the main ones have signs that confirm that they were created by bomb explosions during the secret war on Laos:

Some of the jars here at site 1 have been toppled, damaged or split open by bomb explosions, especially the ones found right next to the bomb craters. In fact, you can find bomb craters at several of the jar sites, often right next to clusters of jars like you see here.

Bomb explosions however are not the only forces at work here and even far away from the bomb craters you still find jars that have been split in half or had their tops broken off leaving just a stump remaining:

The other main group of jars in Site 1 is on a small hilltop just to the north of the hill that contains the cave. A pathway leads you to the top of this hill:

Up here atop the hill, you can see some much larger jars, some of them towering over 2 metres in height:

The largest jar of all is found here. It’s about 2.5 metres in diameter, 2.57 metres in height and is estimated to weigh about 6 tonnes.

This jar is known as the king’s cup or to the locals as ‘Hai Jeuam’, because it is believed to be the victory cup that the mythical King Jeuam drank from, according to one of the legends.

You may have noticed that the King’s cup has a ‘neck’ or a raised inner rim. While this rim design is found on a few other jars, the majority of the jars have the flat-topped rim that you’ve seen on the jars in the preceding images.

A few jars also have a sunken inner rim but this is a much scarcer rim type, found only at a few sites (site 27 is one site where it can be found).

But could the presence of such rims suggest that the jars were once fitted with lids? Perhaps, but no lids have ever been found in situ. It's possible that most of the original lids were made of perishable materials like wood ....or maybe there simply never were any.

What have been found are hundreds of stone discs but these are believed to be another kind of grave marker rather than lids. There's a stone disc here at Site 1 with concentric circles but we didn't get a picture of it. We'll instead later show you a picture of the stone disc we found at Site 2.

By the way, there is an excellent view from up here on the hilltop that overlooks the first group of jars:

If you go to the outskirts of the site, you might come across one or two of the trenches that were dug here when it acted as a battlefield during the war. There are more bomb craters to be found scattered around the outskirts also. However, it's not advisable to stray too far from the trails here because of the UXO risk.

Well, that's about all we have to say about site 1. Now let's take a look at site 2.

Site 2- Hai Hin Phu Salato

Site 2 Layout

Site 2 is found about 23 km south of the main market in Phonsavan.

Getting there: Take highway 1D south for about 9km and take the right turn about 2km after Ban Nam Tom. Follow this road for another 10 km and take the left turn at Ban Nakho. Now follow this road for another 1.5 km and you’ll reach the ticket booth. The jar site itself lies a few hundred metres past the ticket booth.

Site 2 is a lot smaller than site 1, with 93 sandstone jars and 14 stone discs (of which we only found one). It's divided into two different groups of jars, which lie on hill crests on either side of a central gully that acts as the access road. See the map for a better understanding.

If you want to circumvent the ticket booth there is a discrete side trail leading up to the hill crest on the west side of the gully (not marked on this map), which starts about 150m before you reach the ticket booth.

There are many pine trees scattered about this site, especially up on the ridge and along the gully. During our visit they were releasing clouds of yellow pollen when the boughs would sway in the wind.

Upon arriving, we first went to explore the group of jars up on the ridge to the west of the central gully. There are over a dozen jars up here, scattered here and there among the trees. We found two jars that had fallen over on their sides:

.jpg)

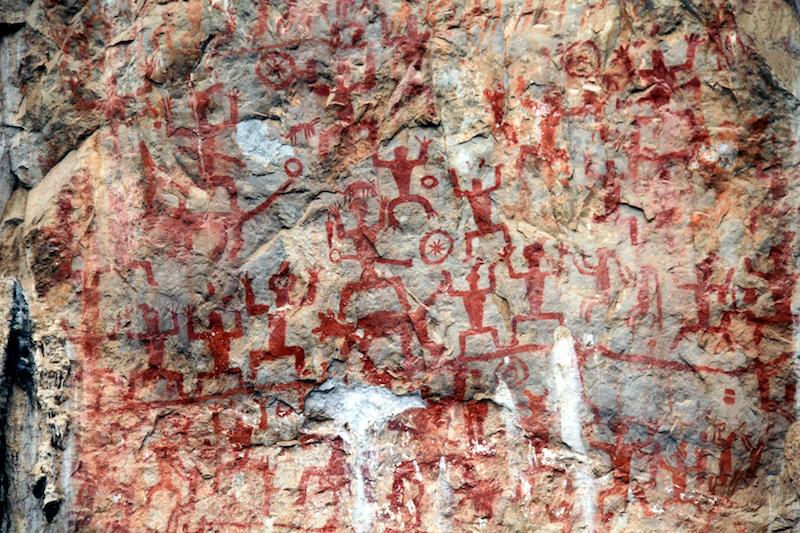

There’s a fascinating stone disc lying on the ground up here, with carvings of concentric circles and a central relief figure that looks quite human-like.

The stone disc at site 1 (which we didn't get a picture of) has the same concentric circles pattern but lacks the central figure.

Some archaeologists have drawn parallels between these figures and the squatting figures with arms raised in the air that are found at the Huashan rock paintings site along the Zuojiang River in Guangxi of Southern China.

There's allegedly a strange animal-like carving on one of the jars up here, which depicts two eye sockets in an oval-shaped face, topped by a feathered headdress. It closely resembles a carving found on the foot of an ancient bronze bowl that was excavated at Nhan Nghia, Quang Ngai Province, central Vietnam. Good luck in finding it!

Another good reason to head up onto the ridge here is the views. It’s important to take a moment to soak it all up:

From up here you get a sense of just how deforested the landscape around Phonsavan truly is.

However, in this case this it’s not due to the rampant logging that’s happening in Laos but has more to do with the consequences of the chemical spraying by the Americans during the Vietnam war.

Because this area receives less rainfall than other parts of Laos, the agent-orange that the area was sprayed with has been slow to leach out of the soils and trees remain unable to regenerate.

After exploring the ridge up here for a while, we headed back down into the gully and then back up the slope to the other part of site 2 where jars are found.

The jars here on the east side of the gully are found within a pleasant grove of trees where dappled light falls upon the woodland floor and the focal point is this very old and charismatic tree that the jars are scattered around:

It's interesting to ponder the fact that the jars must have been here long before this tree germinated from a seed. Nevertheless, when the tree began to grow and exert its influence, some of the jars inevitably got in the way and the tree had the final call.

On the other side of this big tree, there is a long, slender jar that has toppled over; most likely it was pushed over by the tree's growing and rapidly expanding surface roots.

Nearby, you'll find other trees that have incorporated jars into their trunks or roots as they grew.

With other trees, the roots must have somehow forced their way through cracks or faults in the jars and split them apart into two halves.

Nature it seems, always wins the battle against man.

It's actually possible to walk to jar site 3 from here if you feel up to it. According to the map, the hike will take about 1 hour and you have to cross fences and walk through fields near the end.

Site 3- Hai Hin Lat Khai

Site 3 Layout

Site 3 is located about 25km from the main market in Phonsavan, a few kilometres further south of site 2.

To get there, head out the same road for site 2 but go straight through Ban Nakho (instead of turning left for site 2) and continue for about 4km towards Cha Ho village. Take the left fork before reaching Cha Ho and continue for about 1.5 km to Ban Xieng Di village. There’s a right turn in the village leading you to the ticket office at the entrance to site 3. Beyond the ticket office, there’s a short walk through some rice fields to actually reach the area with the jars.

We didn’t find any easy way around buying a ticket here but you may be able to gain a free entry if you’re friendly to the ticket issuer and have a good excuse for not being able to buy a ticket.

Here at site 3, there are 247 jars made from sandstone and 45 stone discs.

The main group of about 150 jars is found within a peaceful grove of trees and there are a few stone discs lying around here too.

Within the grove of trees you become immersed in the serenity and tranquility of the place as you walk among the ancient stone jars. At sunset, beautiful golden light filters through the leaves of the trees and bathes the jars in its golden warmth:

While wandering about the site, we came across this very plain, undecorated stone disc. Or could it, in this case, be a lid for one of the jars?

Walking paths lead out from this main group to 3 other smaller sites to the south and east, call them sites A, B and C (see the map).

Site C only has one solitary jar. There are bomb craters near the path on the way to sites A and B also.

By the time we had finished exploring this main group of 150 jars, it was already becoming too dark for further exploration so we missed these 3 smaller sites.

Exploring Phu Keng Mountain

Several unfinished jars or ‘preforms were found on the hill slopes of this mountain, which reaches an elevation of 1,400 metres and is found 14km west of Phonsavan.

There are many boulders of suitable size here on the hill slopes for creating the jars. Archaeologists believe that this mountain may have been a quarry site for some of the jars at site 1.

Getting there: To get to Phu Keng, take highway 7 west for about 7-8 km until you see a left turn with a signboard saying it’s another 7km to the mountain. Follow this long and very scenic road all the way until you reach the foot of the mountain.

You may have to pay a small entrance fee when you arrive here. We didn’t but we did arrive quite late in the afternoon.

A concrete pathway begins by ascending gradually through a pine forest, until steps begin to appear. The steps are gentle and gradual to begin with but become quite steep as you continue climbing the mountain. The steps bring you higher and higher and seem to go on and on endlessly. In fact, in order to reach the summit you’ll have to climb over 1,000 of them. Bring water and make sure you’re in decent shape if you’re going to attempt this.

When you’ve climbed high enough, you’ll start encountering jar quarry sites. These are labeled ‘Jar Quarry Site 1’ or ‘Jar Quarry Site 2’ etc. There are several of them and they’re basically just steeply sloping shallow gullies off to the side of the trail with many scattered boulders.

If you poke around these quarry sites a bit, you’ll see there are several unfinished jars lying around that were seemingly abandoned. A word of warning though: watch your step. There is UXO around this area and unexploded bombs can be found among the unfinished jars so it’s best to try to stay on the path.

Some of the unfinished jars have just been roughly shaped on the outside and only partially hollowed out. Some even have trees using them as plant pots. You can see evidence of tool marks on some of the jars and archaeologists have assumed from these marks that the jars were sculpted with iron and bronze chisels. They may have been transported from here to site 1 by elephants.

Moving further up the mountain and approaching near the summit, there is a secret tunnel that was used as a bomb shelter by North Vietnamese soldiers during the war.

_1.jpg)

The concrete tunnel is about 70 metres long and begins as a narrow corridor about 1.6 metres high and later widens to about 5-6 feet. It might be blocked off now at the far end although in the past it was possible to emerge at the other end for a panorama of the Phoukoud valley. You’ll also find small rooms and sleeping chambers just off the main tunnel so bring a headlamp or flashlight because it’s pitch black inside without one.

There's also a small cave near the summit that you can locate if you have the time or motivation but we didn't explore this.

If for nothing else, it’s worth climbing up here for the panoramic views from the summit:

_1.jpg)

On the descent we half-ran down the mountain as it's more exciting that way. Driving back on the motorcyle from Phu Keng, we witnessed a breathtaking view of the Xieng Khouang plateau from the road leading up to Phu Keng mountain:

We were treated to a spectacular sunset that evening, which was the perfect conclusion to both our day and to our short-lived but extraordinary foray into the beautiful and mysterious land of the plain of jars.

Watch video:

This video covers not only the plain of jars but also scenes from the town of Phonsavan and other sites around the town. If you just want to see the plain of jars skip to 0:54 in the video.

Recommended Guidebook: Lonely Planet Laos

Have you ever visited the plain of jars in Laos? Please tell us about your experience in the comment section below.

JOIN OUR LIST

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

ABOUT US

Our names are Eoghan and Jili and we hail from Ireland and India respectively.

We are two ardent shoestring budget adventure travellers and have been travelling throughout Asia continuously for the past few years.

Having accrued such a wealth of stories and knowledge from our extraordinary and transformative journey, our mission is now to share everything we've experienced and all of the lessons we've learned with our readers.

Do make sure to subscribe above in order to receive our free e-mail updates and exclusive travel tips & hints. If you would like to learn more about our story, philosophy and mission, please visit our about page.

Never stop travelling!

FOLLOW US ON FACEBOOK

FOLLOW US ON PINTEREST

-lw-scaled.png.png)