The Ultimate Guide To Visiting Borobudur: Largest Buddhist Monument In The Entire World

At the time, we had been gradually traversing the island of Java, Indonesia from west to east and had reached the city of Yogyakarta, the cultural centre of Java.

While staying in Yogyakarta, we heard tales of a colossal, ancient Buddhist monument, constructed from over 2 million stone building blocks, perched upon a small hilltop and surrounded by a lush, fertile plain.

The monument had been abandoned and lost in the jungle for hundreds of years but following its rediscovery in 1814, it had been gradually restored to much of its former glory.

This sounded to us like a very mysterious and fascinating place to visit. It piqued our curiosity.

From the moment we learned of its existence, it seemed that we were inexorably destined to set foot upon this ancient monument and experience its raw energy and magnificence for ourselves.

So it was that we came to discover the wonders of Borobudur, the largest Buddhist monument in the entire world.

Borobudur's significance

Borobudur is an ancient Mayahana Buddhist monument and the largest such monument in the entire world.

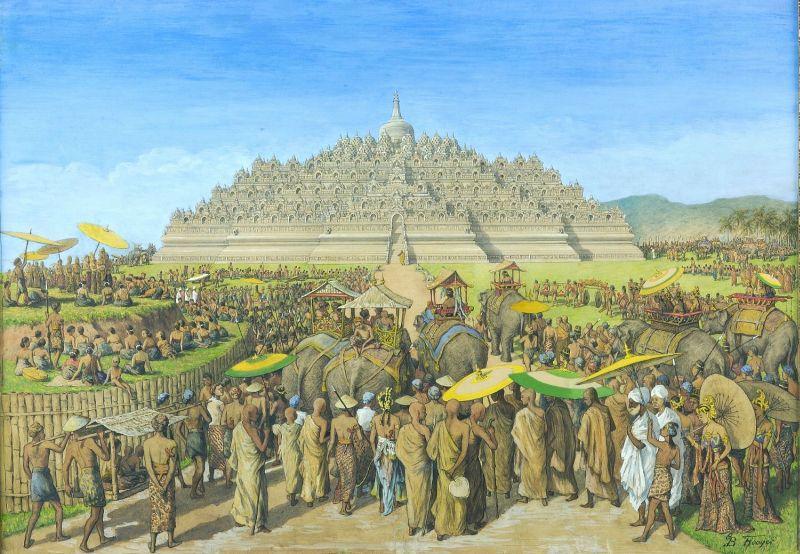

Its original purpose is not clearly known, but today it fulfills several important functions; acting as a shrine to Lord Buddha, a place of pilgrimage for devout Buddhist worshippers and as a major tourist attraction and source of revenue for the Indonesian government.

During Vesak (Buddha’s birthday), held on the night of the first full moon in May, an elaborate and colourful multi-day festival is held at Borobudur and it ends with an enchanting candlelit procession to Borobudur from another nearby closely-related ancient temple called Candi Mendut.

Regarding tourism, the monument in fact receives over 2 million visitors every year, 80% of which are domestic tourists. It's the single most visited tourist attraction in Indonesia.

With the absurdly high entrance fees for foreigners and rapid commercialization of Borobudur, the monument's cultural and spiritual significance is now rapidly becoming dwarfed by its commercial significance to the Indonesian Government and other beneficiaries.

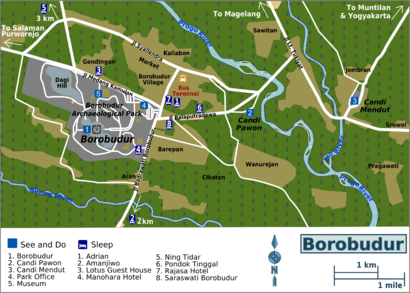

Borobudur's Location

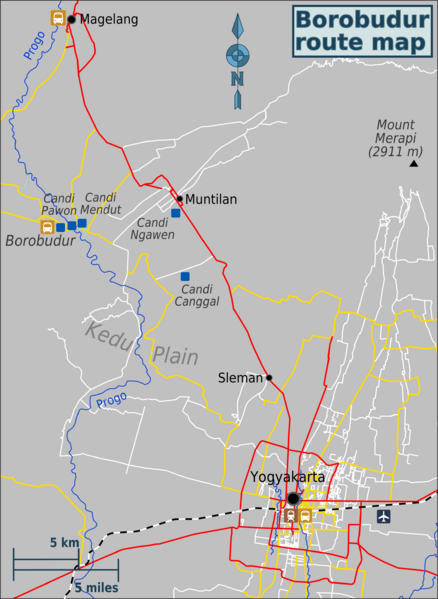

Borobudur temple is located 17.4 km from the nearest city of Magelang and about 40km to the northwest of the city of Yogyakarta, in Central Java.

It lies between two rivers (the Progo and the Sileng) and rather unfortunately, between two twin volcanoes (Merapi-Merbabu to the north-east & Sundoro-Sumbing to the north-west).

The monument was built on a slightly elevated area and lies at 265m above sea level. The surrounding verdant ‘Kedu Plain’ is a highly fertile agricultural area and is known as ‘the garden of Java.’

Much of the immediate area in the environs of the monument has been designated as the Borobudur archaeological park. The entire area is off-limits (in theory) to those without a valid ticket. The park also features several adminstrative buildings and two interesting museums for those who are seeking additional information and interpretation.

How To Get To Borobudur

There are a few different ways to get to Borobudur. You have to first reach Java of course. If you’re coming from Yogyakarta, the cheapest way is by public bus. The most convenient is probably by hiring a taxi.

By air:

If you’re flying into Java to see Borobudur, the nearest airports are Yogyakarta’s Adisucipto International Airport and Solo’s Adisumarmo International Airport.

These airports are well connected domestically but international connections are more limited. You can still fly in from Singapore or Kuala Lumpur.

From Yogykarta Airport it’s then possible to take a fixed-price taxi to Borobudur for 190,000.

By bus:

You can easily get to Borobudur from Yogyakarta by public bus. Few tourists actually do it this way, despite the fact that it’s fairly straightforward.

Buses depart from the Jombor Bus terminal in Yogyakarta on a fairly regular basis. The bus terminal can be reached either by taxi or by taking the Trans-Jogja buses 2A or 2B from central Yogyakarta. If you’re familiar with Malioboro St. you can easily jump on the Trans-Jogja here for a few thousand rupiah.

Once you reach Jombor terminal, you can jump on a bus for Borobudur. Ask around to find the correct bus.

The bus to Borobudur should take around 60-90 minutes depending on traffic and should cost around 25,000 rupiah. Don’t let the ticker issuer overcharge you.

When you get down at Borobudur, it’s a 5-10 minute walk to the entrance. Don’t believe any of the touts (motorcycle taxi drivers) when they tell you it’s a 2km walk from the bus stop.

By Van/Minibus

There are various private tour operators in Yogyakarta that will transport you right to the gate of Borobudur by van or minibus. Some operators combine a tour of Borobudur and Prambanan in a single day. Prices for the tours vary wildly so ask around and bargain.

Be aware that tour operators will often stop the vehicle at batik shops and silver factories along the way to try to make a commission from tourists’ purchases.

We don’t recommend this option personally as it’s more expensive and you’ve little freedom to explore the temple at your own pace. You also have no possibility of avoiding the entrance fees if you do it this way.

By train:

The nearest train station to Borobudur is the Yogyarta railway station (formerly known at Tugu), located in central Yogyakarta. This station is well connected with other cities in Java like Jakarta and Surabaya. From the station in Yogya, you can transfer to Borobudur by bus or taxi.

By motorcyle:

It’s possible to rent a motorcycle in Yogyakarta. It should cost about 50,000 or 60,000 rupiah for a full day and you may have to leave your passport as collateral since the bike won’t be insured.

We found several small rental businesses around the Malioboro St. area, catering to foreign tourists. If you have a good maps app on your phone and you’re a confident driver, you can easily bike the 40km to Borobudur by yourself.

Just be careful not to attract too much attention from the police if you don’t have some kind of license to show. Any driver’s license should work in most parts of Java; they police aren’t usually aware they should be looking for an international driver’s license like they are in Bali.

Road conditions aren’t particularly safe and can be a little chaotic in places but you get used to it after a while. If you’ve driven a bike without issues in other parts of SE Asia before you’ll be fine.

By Taxi:

If you have plenty of money to blow, you can always take a taxi from central Yogyakarta to Borobudur. The journey takes around 60-90 minutes depending on traffic. Price should be around 200,000 rupiah.

From the Yogyakarta airport, you can also take a fixed price taxi to Borobudur for 190,000 rupiah.

Once you're inside the archaeological park, there is a toy train (for a small fee) to shuttle you to the foot of the monument. The monument itself can only be explored on foot.

Where to stay

Most visitors to Borobudur stay in Yogyakarta, where there’s a range of accommodation options including budget, mid-range and high-end options. Sometimes the better rooms can be scarce however and you may prefer to book onlineinstead.

A smaller number of visitors stay in nearby Magelang, which is only 17.4 km from the monument.

If you want to really understand Borobudur, you’ll need to devote 2 or 3 days to the monument and for that it’s better to stay in the immediate area outside the park. There are several guesthouses (losmen) and basic hotels in Borobudur village, although the prices are (predictably) somewhat inflated here compared to normal Indonesian standards.

When to visit Borobudur

Borobudur is at its most atmospheric during sunrise or sunset. However, busloads of tourists like to arrive at sunset for their selfie snaps so the best way to beat the crowds is to arrive before dawn.

The Manohara Hotel can arrange pre-dawn entry into the monument for you and it offers greatly discounted rates to those who stay at the hotel.

Entrance Fees

Unfortunately, the entrance fee to Borobudur for foreign tourists is distastefully high, as is the case with many high-profile UNESCO world heritage sites. Native Indonesians, holders of Indonesian work permits and even foreign students don’t have it so bad but for everyone else, it’s a tough pill to swallow.

Adult Foreigners: 280,000 Rp (USD $22)

Adult Indonesians & Holders of Indonesian Work Permit: 30,000 Rp (USD $2)

Non-Indonesian Registered Students: 110,000 Rp (USD $8)

So what if you're a broke backpacker and you really want to see Borobudur but can't because the entrance fee will threaten you with bankruptcy? Well, it is possible to avoid the entrance fee if you follow our directions.

By the way, it may be best not to attempt this if you're unfamiliar with sneaking into UNESCO world heritage sites. The method that follows requires a little bit of luck to pull off but we know it works:

Once you’re at the main entrance to the monument, start heading south along Jl. Bandrawati. You should see a green spiked fence running along the edge of the compound on your right hand side.

As soon as the green fence ends, there should be a very discrete, narrow little laneway and a little stream on your right hand side. Head down this laneway to the west and you’ll find yourself walking through some paddy fields.

Keep heading west through this field for some time and keep looking at the fence on your right hand side for openings. After a few hundred metres, there is a concrete culvert that you can crawl through to get under the fence and into the compound.

Once inside the compound, there is a road with some occasional traffic in front of you. Try to wait for a quiet period and then dash across the road (casually) towards the monument, which will be straight ahead to the North.

You’ll then reach a gate (probably locked), with steps leading up to the hilltop the monument sits on. Climb over the gate and carefully ascend the steps, watching out for guards on patrol above. Usually they’re pretty lax and they won’t get suspicious if they see you down on the steps and you pretend you’re just taking photographs.

Congratulations, you’re in. We didn’t notice that anybody was checking tickets at the monument so you should be fine if you’ve made it this far without raising any eyebrows.

Hiring Guides

The main reason you’d hire a guide at Borobudur is to have him explain the bas-reliefs, which read like some kind of encrypted message without a guide’s expert knowledge.

Most good guides will charge 75,000 -100,000 Rp per hour for their expertise. Not the cheapest but if you’re really interested in understanding the reliefs then it’d probably be worth it.

You can just turn up and find a guide at the park on any busy day or you can organize one beforehand. Guides may in fact approach you if you turn up without one. Ask your guesthouse or any of the local tour agencies about arranging guides in advance.

A brief history of Borobudur

The history of Borobudur can be summarized by four main stages; the construction, the abandonment, the rediscovery, the restoration. We'll also mention some important recent events in its history.

The construction

The construction of Borobudur began around the year 750AD, during the peak period of the Sailendra Dynasty's rule over the Mataram Kingdom, which was heavily under the influence of the Srivijayan empire.

Nobody can be sure exactly who commissioned the construction of Borobudur and why. Its origin is shrouded in mystery. What is known is that Hinduism and Buddhism seemed to co-exist peacefully during that time period (the Hindu temples of Prambanan were built around the same time).

The construction is estimated to have taken approximately 75 years and to have been finally completed around 825 CE. Undoubtedly, a large number of men, both skilled and unskilled were involved in the project.

A lot of heavy physical labour was required to source and transport the heavy stone blocks from nearby riverbeds to the top of the hill that Borobudur was built on. Detailed bas-relief carvings and other stone sculptures required skilled craftsmen.

The abandonment

Borobudur was at some point abandoned to the jungle but nobody knows exactly when or why this happened. Various theories have of course been suggested to explain the abandonment.

One of the most likely explanations is that the abandonment was caused by a series of volcanic eruptions that forced the then capital of the Medang Kingdom to relocate to East Java.

Another popular explanation is that it was abandoned when the local people converted to Islam in the 15th century.

Although abandoned, the temple wasn’t completely forgotten and folk stories soon began to associate the temple with bad luck and superstition, after ill fate had befallen many people who had had dealings with the temple site.

The rediscovery

From 1811-1816, Java was under British administration. In 1814, the then appointed governor was Lieutentant Governor General Sir Thomas James Stamford Raffles.

An avid collector of Javanese antiques, Raffles had heard tales of an ancient ‘lost’ monument, hidden deep in the jungle, which piqued his curiosity. He soon sent a Dutch engineer called H.C Cornelius and a team of 200 men to investigate.

With much toil and hard work over a period of 2 months, they hacked at the thick jungle undergrowth and dug away much of the Earth and volcanic ash covering the monument.

The Dutch continued the task of unearthing the monument and in 1835 it was finally fully unearthed. Detailed studies were then made of the monument and reports were published during the late 1800s.

Unfortunately, appreciation of the monument was slow to develop and many valuable Buddha images and other treasures were looted from the monument in the years following its rediscovery. Some important figures were even permitted by the colonial government to take as many items as they pleased from the monument. Some of these artifacts have now ended up in the National Museum in Bangkok.

Also, because the protection of the jungle had been removed, the monument was now exposed to the elements and it began to face problems caused by poor drainage. A restoration effort was badly needed.

The restoration

The first restoration project took place under the leadership of Van Erp, over a five-year period from 1907-1912. However, the project only addressed the less important issues like reuniting buddha heads with their statues and cleaning the sculptures. Despite the efforts, unsolved drainage problem began to threaten the monument with collapse. From 1975 to 1982, the Indonesian government collaborated with UNESCO in the biggest restoration project yet seen.

During the 7-year period, all the terraced levels of the monument were disassembled block by block. The blocks were all then specially cleaned and treated and the drainage problems afflicting the monument were finally addressed before the blocks were meticulously put back together like a jigsaw puzzle. The effort involved a team of 600 people and a total cost of about $6,900.

In 1991, Borobudur was finally declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site and since then, its popularity with international tourists has increased dramatically, with all the attendant upsides and downsides of mass tourism.

Recent events

The two most significant recent events that affected the monument were the 2010 eruption of the explosive Mount Merapi and the Muslim bombings in 1985. An earthquake in 2006 did not affect Borobudur.

The 2010 eruption of Mount Merapi

In late 2010, Indonesia’s most active volcano erupted, blasting ash into the air to reign down upon Borobudur. Mount Merapi is only 28km north-west of Borobudur and it erupts every 5-10 years.

The layer of ash that coated the monument was over 1 inch thick and it also found its way into cracks between the blocks and clogged the drainage system. Experts feared the acidity of the ash would damage the andesite stonework.

The surrounding vegetation was also killed or damaged by the heavy ash fall, which destabilized the local climate.

UNESCO came to the rescue with a $3 million donation to help remove the volcanic ash from the monument and start a tree-planting scheme to restore the vegetation to the area. Blocks had to first be disassembled and later put back together to remove the ash that had penetrated deep into the monument.

The Muslim bombings

In January 1985, radical Muslims sneaked into the monument and hid 11 bombs inside several of the perforated stupas on the upper levels of the monument. 9 of the bombs exploded, scattering the stone blocks everywhere and damaging many of them. Since then, security has been tightened with 14 monitored CCTV cameras now operating round the clock.

The basic design of Borobudur

Borobudur’s overall design is that of a step pyramid, measuring 123m x 123m along the base of the monument. The steps or platforms are not shaped as perfect squares due to the numerous indentations at each of the four corners.

The monument attains a maximum height of 35m, measured from the ground to the top of the central stupa on the uppermost tier.

What’s really interesting is the pattern the monument creates when viewed from above:

The pattern is that of a Mandala, a symbolic representation of the cosmos used by Tantric (Tibetan) Buddhists. Indeed, Borobudur is often referred to as the Mandala in stone.

The four sides of the monument face the cardinal directions and there are 4 stairways leading to the top of monument, one in the centre of each side of the monument. Each stairway passes through several ornate archways on the way to the upper levels of the monument.

The main entrance is on the Eastern side of the monument and this is the entrance virtually all the tourist visitors enter through. To reach the entrance, you have to first ascend the main staircase from the plains below to reach the top of the small hill that Borobudur sits on.

The Levels

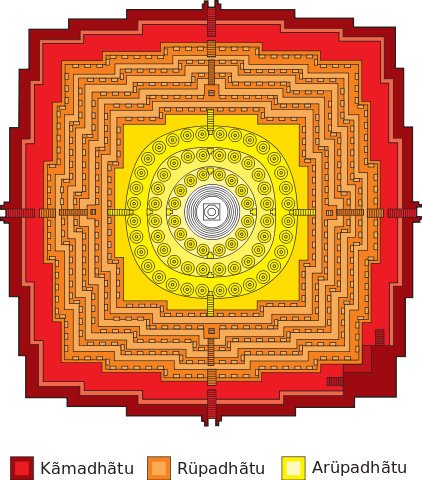

.png)

The monument is divided into 9 distinct platforms, of which the first 6 platforms are square and the upper 3 are circular in shape.

The monument is also conceptually split into 3 broader levels, which correspond to the three ‘realms’ in Buddhist cosmology. The foundation or base level (level 1) represents kamadhatu (the world of desires). Levels 2-6 of the monument represent rupadhatu (the world of forms). The upper 3 levels 7-9 represent arupadhatu (the formless world).

Each level of the monument represents one stage of enlightenment. As pilgrims circumambulate the monument and ascend through the levels, they are supposed to decipher and contemplate the life lessons and teachings found in the wall sculptures (bas-reliefs), guiding them on a symbolic journey through the stages of enlightenment.

Level 1: The base encasement (Kamadhatu)

The first level or base level actually consists of two distinct levels. The lower base level is only a few feet wide. The upper base level is a wider platform about 7 metres in width, which allows you to walk around the monument.

The entire base level actually encases the original ‘foot’ of the monument, hiding it from view (see diagram above).The encasing base seems to have been added after the monument was built, but the reason for its addition is still a mystery.

The hidden foot is only known about because it was discovered by accident in 1885. It was found to contain over 160 relief panels and also some inscriptions with instructions for the sculptors. Today, only the south-east corner of the hidden foot is revealed to visitors.

The base level conceptually represents the world of desire or the lowest level of existence and the world that men are born into. This world is associated with suffering and egoic traits like greed, dishonesty and envy.

Levels 2-6: The world of forms (Rupadhatu)

The next five levels consist of 5 square platforms of diminishing size and height as you go upwards.

The first 4 of these 5 levels confine you to narrow 'galleries' or terraces, which run around the entire perimeter of the monument on all 4 levels. The galleries are only about 6 or 7 feet in width and due to the indented square shape of the monument, each gallery segment is quite short, so that you can never see too far ahead.

The galleries were designed to be walked in a clockwise direction. If you were to walk around all of the galleries on all 4 levels, you would have walked a total distance of 1.2 km. The galleries are not all of equal length however, due to the pyramidal shape of the monument. The breakdown of the gallery lengths is as follows:

Level 2: 360m

Level 3: 320m

Level 4: 288m

Level 5: 256m

Balustrades line the perimeters of each of the 5 rupadhatu levels, which include the 4 terraced levels plus the 6th level. When walking along the terraces, the balustrades are high enough that they block the view of the surrounding landscape, leaving you with a sense of confinement.

The outward faces of the balustrades display seated Buddha images inside niches. Many of the niches are badly damaged, leaving some of the statues exposed.

On the inner and outer facing sides of the balustrades and on the platform facades, you’ll see rows of bas-relief panels; artistic wall carvings that were created by skilled sculptors. There are over 2,400 bas-reliefs panels distributed throughout the various levels of the monument.

These 5 middle levels represent the world of forms, an elevated level of consciousness where beings are more detached from the world and no longer governed by desires or subject to extremes of pleasure or pain.

Levels 7-9: The formless world (Arupadhatu)

The upper 3 levels feature 72 small stupas, arranged in concentric circles around the central large stupa.

The lowest circular platform has the greatest diameter and has 32 stupas. The next platform up has 24 stupas and the top platform has only 16 stupas.

Of all 72 stupas that should be present, one or two are badly damaged, exposing the Buddha images that were originally inside and incidentally, making for some amazing photo opportunities.

All the other stupas are in good condition and are perforated with decorative holes. The holes in the stupas on the lower and middle circular levels are diamond shaped while those in the stupas on the highest level are square-shaped:

The Indonesian people are very superstitious and they believe that if one reaches inside one of the stupas and touches the Buddha image inside, good fortune will come one’s way.

The principal central stupa sits on the 9th and highest platform of the monument and is about 16 metres in diameter. The present-day stupa is missing its pinnacle, the form of which is unknown.

During the first restoration led by Van Erp, the pinnacle was reconstructed as a three-tiered stone umbrella called the chattra but was later dismantled since there weren't enough original stones used in reconstructing it. The chattra is now displayed in the Karmawibhannga museum near the monument.

The stupa is said to have two unconnected hollow chambers inside of it. During restoration work, teams opened up the stupa and supposedly found an unfinished buddha image inside it, in the bhumiparsa mudra (earth touching gesture), which corresponds to the east cardinal point.

As you emerge onto the upper levels, everything opens up and views of the environs are revealed, in contrast with the narrow, claustrophic galleries below. All the clutter and details of the terraces disappear and a very simple geometric pattern is revealed.

.jpg)

This dramatic change symbolizes a freeing of the mind as one transitions from the rupadhatu level into the arupadhatu level of enlightenment.

The curious ratio

An interesting physical ratio exists between the dimensions of the 3 ‘realms’. If you imagine the base level as the ‘foot’, the 5 middle levels as the ‘body’ and the 3 upper levels as the ‘head’, then the ratio of width of foot: width of head: width of body and also height of foot: height of head: height of body seems to be 4:6:9.

This ratio is thought to have some calendrical and astronomical significance.

The building blocks

.jpeg)

Over two million andesite blocks were cut and transported from a nearby riverbed to build Borobudur. The heavy rectangular blocks, many weighing as much as 100kg, had to be hauled laboriously up the hill that Borobudur rests on.

The block material, andesite, is an extrusive igneous rock that's usually some shade of gray in colour. The Indonesians simply know it as 'temple stone'.

The interlocking blocks were fitted together with various indentations, nobs and dovetail joints. No mortar was used in the construction. After the blocks were in position, the bas-reliefs were carved in situ by skilled sculptors.

Back when Borobudur was first built, the blocks would not have been visible as they are today. Evidence suggests that the entire monument was originally covered in a layer of white plaster and then painted, making Borobudur a colourful beacon that glinted in the sun and that could be seen from the plains below.

The bas-reliefs

Borobudur is renowned for its incredible bas-reliefs (wall carvings), which in total number 2,670 panels. Of the 2,670 panels, 1460 are narrative and the 1,210 are decorative.

Many of the bas-reliefs depict scenes of daily life from 8th century Java and have been used by historians to learn more about the architecture, weaponry, fashion, transportation methods and other aspects of life during that time period.

All the different social classes of that time are depicted in the bas-reliefs, from the commoners and forest hermits to the noble classes. Many of the reliefs also depict mythical guardian deities from Buddhist mythology.

All the reliefs are distributed amongst levels 1-5. Most of the reliefs on the kamadhatu level are hidden to the public (except at the south-east corner). The remaining reliefs are distributed amongst the walls and balustrades of the four gallery levels.

The narrative reliefs are grouped into 11 series which encircle the monument with a total length of 3,000 metres. The first series, numbering 160 panels, is found on the hidden foot of the monument. The other 10 series are found on the 4 gallery levels.

Since the monument is supposed to be encircled in a clockwise direction (a ritual called pradaksina ), the reliefs on the facades are read from the right to left, while those on the balustrades are read from left to right.

.jpg)

There are four main narratives found in the relief panels and they are:

The Birth and Life of the Buddha:

120 panels on the wall of the first gallery depict the biography of the Buddha. The story starts with the descent of the Buddha from Tushita Heaven and ends with his first sermon in Deer Park near Benares.

The main story is preceded by 27 panels which show the preparation for the birth of the future Buddha as Prince Siddartha.

His mother Queen Maya, the wife of King Suddhodana had dreamed that a white elephant with six tusks entered her right side, which was interpreted to mean that she would conceive a child who would become a future ruler or Buddha.

When the baby was due, she went to the Lumbini park outside the Kapilavastu city (in Nepal) and gave birth to the prince under a plaksa tree.

After depicting the birth, the panels continue to show the events that occur right up until the time that the prince becomes the Buddha.

The Law of Karma:

The 160 hidden panels depicting the law of Karma are mostly located on the hidden foot of the monument. You can only view a few of these panels where a portion of the hidden foot is revealed at the south-eastern corner of the monument. You can however view many of the previously photographed hidden panels at the Karmawibhangga museum.

The reliefs narrate stories illustrating the nature of karma and also depict examples of praiseworthy (charity, alms giving etc.) and blameworthy (lying, cheating, stealing etc.) behavior.

The reliefs aim to demonstrate the cause and effect relationships between the different kinds of behaviours so that people can be guided towards the proper conduct.

The Jatakas and Avadanas:

The Jatakas depict stories of previous incarnations of the Buddha before his birth as Prince Siddhartha. The Avadanas are similar but the main characters of the stories are not Bodhisattvas (enlightened beings).

The stories aim to demonstrate the effect that noble deeds in former lives will have on the next life.

In the 1st gallery (level 2), there are over 500 reliefs depicting the Jatakas and the Avadanas and you'll also find about 100 panels of this narrative on the balustrades of the 2nd gallery (level 3).

The journeys of Sudhana searching for ultimate truth:

This is the story of Gandavyuha, told in the last chapter of the Avatamsaka Sutra. The story is about Sudhana, the son of an extremely rich merchant and his tireless wandering in search of the perfect wisdom.

In the story, he visits and meets with several personages in search of truth, including bankers, monks, a physician, a king, a queen and other important characters. The meetings are shown in the 3rd gallery.

There are 128 panels depicting the story of Sudhana on the inner wall of the 2nd gallery and the story continues on the 3rd and 4th galleries with 176 and 156 relief panels respectively.

If you want to fully understand the bas-reliefs of Borobudur, you will definitely need a guide. They are perhaps the most inscrutable aspect of the entire monument.

The Buddha statues

The monument theoretically features 504 buddha statues in total, although 43 have gone missing and over 300 are mutilated (mostly beheaded).

72 of the images are found inside the perforated stupas on the 3 circular upper levels (arupadhatu) with the remaining 432 images distributed amongst the 5 square levels (rupadhatu).

The Buddha images in the rupadhatu level were all originally tucked away inside niches on the outward facing sides of the balustrades but today, many of the niche arches are now badly damaged, leaving some of the images more exposed to the elements.

The 432 Buddha images are not distributed equally throughout the 5 levels of rupadhatu. The breakdown is as follows:

1st level: 104 images

2ndLevel: 104 images

3rd Level: 88 images

4thlevel: 72 images

5thlevel: 64 images

The individual statues would have all been each carved from a single stone block and each statue can weigh as much as 200kg.

Much of the beheading of the images probably occurred during the period after Borobudur’s rediscovery when the monument was poorly guarded and thieves and looters had free rein to steal the sacred Buddha heads and sell them on the black market for profit.

Heads from these statues have also ended up in western museums like the British museum in London and the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam.

The mudras (Buddha gestures)

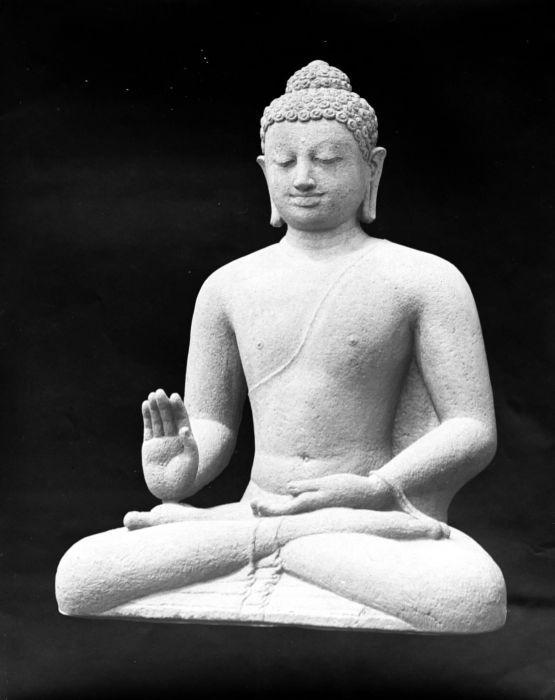

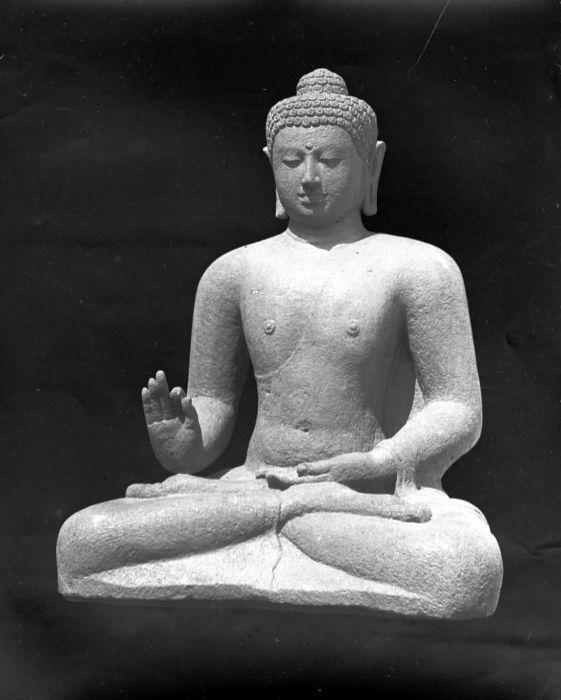

.jpeg)

All the Buddha images face outwards in the cross-legged lotus position, looking at the surrounding countryside.

They are all deceptively similar but there are subtle differences between many of the statues. The differences lie in the variety of different mudras or hand gestures exhibited by the images.

There are 6 different mudras in all to be found in Borobudur.

5 of the mudras are found on the five levels of Rupadhatu and these five mudras represent the five meditating Dhyani Buddhas of Vajrayana (Tantric) Buddhism. The sixth, much rarer mudra is depicted by the Buddha images inside the perforated stupas on the arupadhatu level.

What’s fascinating about the mudras is that they correspond to the five cardinal directions of Mayahana Buddhism (North, South, East, West, Zenith).

4 of the mudras are found on the first 4 terraced levels of Rupadhatu. Every face of the monument (north, south, east, west) has its own corresponding mudra.

On the 5th level however, there is only one mudra found on all four faces of the monument; the zenith mudra.

The six mudras of Borobudur are:

%20(1).jpeg)

Bhumiparsa Mudra: This is the Earth touching Mudra or 'subduing mara' gesture. The right palm rests on the right leg and faces downwards, at the Earth.

This Mudra is found on the balustrades of the east face of the monument on the first 4 square levels of rupadhatu. It symbolizes 'right conduct.'

%20(1).jpeg)

Vara Mudra: This gesture symbolizes the need for charity or benevolence. Similar to bhumiparsa mudra, except the palm of the right hand is held facing upwards, symbolizing the act of giving.

This mudra is found on the balustrades of the south face of the monument on the first 4 square levels of rupadhatu.

.jpeg)

Dhyana Mudra: This gesture symbolizes the importance of meditation. Both hands face upwards and the thumbs touch.

This mudra is found on the balustrade of the western face of the monument, on the first four square levels of rupadhatu.

Abhaya Mudra: This gesture symbolizes 'courage' or 'fearlessness'. The right hand is raised in a vertical position with the palm facing outwards.

This mudra is found on the balustrade of the northern face of the monument on the first 4 square levels of rupadhatu.

Vitarka Mudra - Similar to Abhaya Mudra, this gesture symbolizes 'deliberation'. The right palm faces outwards and the forefinger touches the thumb.

This mudra can be found on the balustrades of the 5th level of rupadhatu, on all 4 sides.

Dharmachakra mudra: This mudra symbolizes the setting in motion of the teachings of the Buddha or the 'turning of the Dharma wheel.' The fingers interlock in a complicated manner.

This mudra is found in the the 72 perforated stupas on the 3 circular levels of Arupadhatu.

The stairways and lion statues

As we mentioned before, Borobudur has four stairways facing the four cardinal directions. In theory, there should be 5 arched gates on each stairway which link levels 1-6 together but in practice some of the arches are damaged or missing.

The arched gates have a kala motif above them, which is a kind of jawless monster from hindu mythology:

The gateways and stairways are also guarded by lion statues, which are distributed amongst several levels of the monument and at the four entrances. They are the guardians of Borobudur. There are 32 lion statues in total.

The Ancient Drainage System

Borobudur is equipped with a very interesting drainage system to channel stormwater down through the levels and prevent flooding.

A system of 100 stone waterspouts, each carved in the form of a makara (mythical sea creature in Hindu culture ) or a monstrous looking gargoyle.

The makara water spouts are associated with the lower levels of the monument and are supported by tiny dwarf figures which squat below them.

Many of the waterspouts are built into the indented corners of the structure but there are others emerging from the mainwalls of the terraces.

The system of waterspouts efficiently transports water down to the base of the monument, carrying it from one level down to the next, until it reaches the base.

The Karmawibhangga Museum

After exploring Borobudur, you have the option to the visit the Karmawibhangga museum, located just a few hundred metres to the north of the monument. The entrance fee is the included within the ticket to Borobudur archaeological park.

The museum displays several interesting exhibits including photographs of the bas-reliefs on the hidden foot of the monument, the unfinished buddha statue found inside the central stupa, over 4,000 original stone blocks that could not be used in the restored version of the monument and the reconstructed 3-tiered chattra (parasol) built by Van Erp during the 1907-1911 restoration project.

The Samudra Raksa Museum

The other museum in the archaeological park is the Samudra Raksa museum. It's found just to the west of the Karmawibhangga museum and the entrance is also covered by the archaeological park ticket.

This museum houses a replica of the Borobudur ship, an ancient double-outrigger seafaring vessel, depicted on many of the bas-relief panels of the monument.

The building of the replica was inspired by a British sailor called Philip Beale, who wanted to prove that long distance trade had occured at the time. He sailed the ship from Indonesia to Ghana and Madagascar in Africa in 2003 to prove his point.

The museum also features some historical information relating to the ancient maritime history of the Indonesian people.

Watch video:

We recorded a few clips of Borobudur in our Yogyakarta video. If you don't want to watch the whole video, just skip to 2:55 where the section on Borobudur starts.

Recommended Guidebook: Lonely Planet Indonesia

If you have any questions about visiting Borobudur that this guide hasn't answered, don't hesitate to leave us a comment below!

JOIN OUR LIST

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

ABOUT US

Our names are Eoghan and Jili and we hail from Ireland and India respectively.

We are two ardent shoestring budget adventure travellers and have been travelling throughout Asia continuously for the past few years.

Having accrued such a wealth of stories and knowledge from our extraordinary and transformative journey, our mission is now to share everything we've experienced and all of the lessons we've learned with our readers.

Do make sure to subscribe above in order to receive our free e-mail updates and exclusive travel tips & hints. If you would like to learn more about our story, philosophy and mission, please visit our about page.

Never stop travelling!

FOLLOW US ON FACEBOOK

FOLLOW US ON PINTEREST

-lw-scaled.png.png)