Summiting Fansipan Mountain: How To Climb Indochina's Highest Peak With No Guide

.jpg)

It was mid-January and we had been staying for several weeks in the mountain town of Sapa, nestled high among the ‘Tonkinese Alps’ (Hoang Lien Mountains) in the northwestern part of Vietnam.

Sapa is a town that initially delights the senses. One is first impressed by the favourable temperate climate, the man-made reservoir with swan pedal boats and the charming old stone catholic church originally built by the French.

Right in front of the church is a large amphitheatre where one can ride two-wheeled hoverboards (self-balancing scooters) or watch the locals play a game known as Jianzi or da cau (like badminton but played with the feet).

The charming Ham Rong (Dragon Jaw) mountain overlooks the town and of the colourfully dressed ethnic minority women (principally Hmong, Dao and Giay) who set up market stalls in town to sell their textiles and forest products, are initially a source of great fascination.

The novelty of the town eventually wore off however and we soon found ourselves taking motorcycle trips out to see the stunning terraced landscapes outside the town and also to visit several of the outlying ethnic minority villages, from which the colourfully dressed women in the town originate.

However, other than an assortment of domestic animals, a few unimpressive waterfalls, a number of repetitive souvenir shops and many colourfully dressed womenfolk, there really isn’t a whole lot to see in these villages and while exploring them, we never felt like we were having much of a real adventure.

We were soon yearning to do something more adventurous, more challenging; something that would test us, stretch us and push us to our limits. It was then when we first heard about a wild, forest-cloaked mountain lying just a few kilometres to the southwest of the town. The local people called it Hua Xi Pan, which means ‘giant protruding rock’, but most people know it as Fansipan.

We began to do some research online and soon discovered that this was the highest mountain in all of Indochina, rising to an impressive 3,143m above sea level.

As we continued our investigations, we began to learn that the slopes of the mountain were not the only obstacles we’d have to overcome if we wanted to set foot upon its summit.

This is a detailed, 10,000+ word travel guide that covers the ins and outs of independently summiting Mt. Fansipan without the aid of a local tour operator.

However, the DIY approach definitely isn't for everyone.

If this seems too daunting a trek to tackle on your own, why not hire a professional local operator to lead you on a 2-day trek to the peak, with accommodation provided for you at one of the mountain campsites (2,800 m elevation) at the end of the first day.

The package also includes cooked meals, water & snacks, porters to carry your equipment, an English-speaking guide and transfer from Lao Cai or Sapa to Tram ton. You can book the Mt. Fansipan trek right here.

The obstacles we faced

Fansipan mountain is unfortunately found inside the Hoang Lien National park and naturally as such is subject to all kinds of frustrating rules and regulations for independent-minded hikers and climbers.

Obstacle 1: The mandatory guide rule

The park rules state that one must obtain a permit to climb the mountain, but ever since a Vietnamese student went missing on the mountain in 2013, it supposedly has been almost impossible for independent-minded hikers to get the permit without also having a guide.

The cost of hiring a guide for the usual 2 day, 1 night climb is normally anywhere between $15-$80 per person depending on the group size (usually 2-8 people). However, not everybody wants to pay for a guide and not everybody has the money to do so either.

We personally hated the idea that we were being forced to hire a guide when we didn’t want one and when we knew we didn’t really need one either.

Blanket rules for the general public’s safety are fine, apart from when they’re applied to experienced hikers. We decided that we would be climbing Fansipan without a guide or not at all.

Obstacle 2: Corrupt park rangers & campsites

From our research, it seemed that the park rangers were exploiting the mandatory guide rule as a way to make some extra cash from those who chose to disregard it.

We had read all kinds of stories and reports online about other people attempting to climb Fansipan without a guide and having it end in failure because of the park rangers.

Many of the reports shared a very similar story; the party of hikers set out early in the morning before anybody was manning the entrance to the park and managed to reach the summit in good time.

Upon returning to the park entrance later on that day however, they were awaited by a gang of greedy park rangers who extorted heavy fines ($50-$100 each) and threatened them with guns and handcuffs to make them all comply.

The reports suggest that this may be some kind of deliberate scam, where the rangers knowingly allow hikers to enter the national park without putting up any warning signs or barriers to entry, so that they can extort money from the hikers for ‘breaking the law’ upon their return.

Other hikers had failed when they had gotten a little lost and accidentally stumbled into one of the campsites where guides or rangers were present.

They were questioned by the officials at the camp and unable to come up with a good excuse for not having a guide. They were then escorted down the mountain to the main ranger office and again extorted heavy fines.

To summit Fansipan, we would have to avoid any unexpected encounters with park rangers and avoid running into any of the campsites, especially during the daylight hours.

Obstacle 3: The cable car station below the summit

In February 2016, the world’s longest 3-rope cable car system (6,295.5m in length) was finally completed, built to transport up to 2,000 tourists per hour from the base station in the Muong Hoa valley all the way up to another cable car station just below the summit of Fansipan.

This is the same number of people that previously made it to the peak over the course of an entire year. The project cost over 200 million USD to complete and smashed two Guinness world records.

When planning our route to the summit, we could see that the cable car ran almost parallel to the trail that we would be taking and that as we would be nearing the summit of the mountain, the trail would be passing directly underneath the cable cars, literally within a stone’s throw.

This was a concern for us as we knew that tourists in the cable cars could potentially spot us walking along the trail below and report us to staff at either of the two stations.

What we didn’t realize at that point was that the cable car station had been built in such a way that it was impossible to access the final stretch to the summit proper without first entering inside the station and proceeding from there.

The station would turn out to be one of our greatest obstacles to reaching the summit without alerting the authorities to our presence. We’ll talk more on that later.

Obstacle 4: Our fear of failure

In the summer of 2016, a very fit and strong 22 year-old athlete called Adrian Webb, from Norwich, England was found dead on the mountain at about 2,800m above sea level, just a few hundred metres below the peak.

The young man had set out to climb Fansipan on his own, taking the most difficult and treacherous of the three known routes to the summit.

We spoke to an official one day at the park entrance and he told us that Webb had gone off the actual trail (which is already very challenging) and attempted a ‘new’ route, which involved some very dangerous free climbing up a waterfall.

From what we gathered, Webb had become trapped during the climb and was unable to continue going up or climb back down. He was unable to call for assistance (his phone battery died before he got into real trouble) and so it’s most likely that he eventually died of hypothermia.

Three years prior to Webb’s death, back in 2013, a 20 year-old student from Hanoi had descended the mountain alone, while his group of four other members remained stationed at a campsite at 2,800m. He allegedly went missing in an area with high cliffs and deep crevices and apparently search parties were unable to locate the body.

Reading all of these tragic stories before our hike really discouraged us and made us fearful and doubtful about how safe an undertaking it really was. It created a mental obstacle in our minds that we had to overcome before setting out.

The story of Adrian Webb in particular was at the back of our minds, as we had planned to go by the same route that he initially took. We just had to remind ourselves that we were not going to be climbing waterfalls or doing anything crazy or risky like that. We would just stick to the ordinary trail and we would abandon the attempt if at any point the path became too hazardous to safely continue ascending.

We’ll now take a look at the three routes that lead to the summit of the mountain and explain why we chose the Sin Chai trail above all the others.

The three trails to the summit

Trail 1: Tram Ton trail

Starting at about 1,850m, this trail begins at the national park entrance near the Tram Ton Pass (heaven’s gate), which is Vietnam’s highest mountain pass. The distance to the summit is about 11km from here and the trail runs in an overall north-south direction, although it twists and turns quite a lot along the way. The total altitude gain is a little more than you’d expect because the final stretch of the trail is quite undulating.

Most guided groups use this route because it’s the easiest and the most common package is a 2 day, 1 night route, with an overnight camp at 2,800m at the end of the first day. It can be done in one day by very fit hikers however. We descended the mountain at night via this trial and we’ve described it in more detail in our account of our experience below.

Trail 2: Sin Chai trail

The Sin Chai trail is named after the small Hmong settlement that the trail begins from. It’s the wildest, steepest, shortest (distance-wise) and the most treacherous of all the three known trails. The route is so overgrown and disused in some parts that it’s inevitable that one will lose the trail a few times. The trail does not require ropes or special climbing equipment as some online sources have wrongly stated, although it is quite precarious in some places. The total length is about 9km and it runs in a roughly northeast-southwest direction. It begins from about 1,380m, so there is more ascent required here than for the Tram Ton trail.

Trail 3: Cat Cat trail

This is the longest of the three trails and begins from the Hmong settlement of Cat Cat village very near Sapa town, at about 1,300m. We don’t know much about it because we didn’t walk it and it’s difficult to find any detailed accounts of it online. It’s said to also be quite challenging and steep but it is certainly not as treacherous as the Sin Chai trail.

Which trail should you choose?

Weighing up all of our research, we concluded that there was really only one practical plan that would truly minimize the risk of getting caught and fined by park officials for being without a guide. Our thought process for deciding on the route went like this:

The only practical way of descending the mountain was via the Tram Ton trail (the Sin Chai route is too steep to safely descend and the Cat Cat route is too long) so we knew that we had to descend that way. We couldn’t descend the trail during the day however because of the risk of getting caught by rangers, so it would have to be at night.

As for the ascent, it would have to be during the day, since the descent would have to happen during the night. However, to ascend during the day undetected by rangers we would have to go by the wildest and least travelled route possible. We therefore decided on the Sin Chai trail as our best option for the ascent.

Our plan was to reach the peak around sunset when the light was fading so that we would be less likely to run into other people on the trail and even if we did, the darkness would hopefully help to make it less obvious that we were two people hiking the mountain without a guide.

How to prepare for the hike

The Sin Chai trail is no walk in the park even for a seasoned hiker and getting to the summit and back undetected by the rangers is also going to be a serious challenge. Succeeding in this endeavor will definitely rely on a large dose of luck but the part that you do have control over his how prepared you are. Here are some things you will need to consider before climbing the mountain.

Your fitness level really matters

Make sure that you’re in good physical shape before you attempt the Sin Chai route. It’s seriously tough, believe us.

We recommend that you undertake a number of challenging day hikes over several days or even weeks leading up to climbing Fansipan, but do make sure that you’re fresh and fully recovered from any previous hikes before you tackle the big mountain.

If you’ve been off climbing other similarly formidable mountains before coming to Sapa, you’ll probably be okay to tackle Fansipan without any prior training.

The weather forecast is critical

You should try to get a detailed weather forecast before you attempt to climb the mountain. Many people have been defeated by the mountain in the past due to bad weather conditions like strong winds and unabating rain, which also makes the trails extremely muddy and slippery.

Know that temperatures can often drop below zero degrees celcius in the higher reaches of the mountain and snow is sometimes a possibility, especially in the winter months. We waited for a string of days when the weather was forecasted to be relatively clear and when there was also a low chance of precipitation.

Navigation is not very straightforward

Since it’s a very wild, disused and overgrown route and the trail is often easy to lose, coupled with the fact that you will be attempting it without a real human guide that knows the route, you should employ several navigational aids to ensure you don’t get lost along the way. Getting lost is one of the biggest threats to you out here, especially if your phone dies before you can call the park rescue teams for assistance.

We had a pretty damn accurate GPS trail of the Sin Chai route on our favourite offline navigation app for travel (maps.me) We suggest you download this app because it works without an internet connection and make sure also that you have GPS tracking enabled on your phone so that you can see your current location on the map. Beware though, the GPS may not work properly at the bottom of some of the river valleys along the way.

You should also download the relevant area on google maps for offline use. The GPS will still work and display your location even though you’re offline. Google maps is also really useful for seeing the topography and you should set it to terrain mode to display the contour lines of the mountain and to allow you to determine your current altitude.

It’s a good idea to also take a few spare batteries for your phone in case it gets discharged before you get down off the mountain. We didn’t take any and thankfully didn’t need any (our iPhone 5 battery was down to about 20% after 18 hours of hiking) because we used the phone sparingly but in hindsight, we probably should have brought at least one spare battery or even a power bank (portable charger) as a backup, just to be on the safe side.

If you want to be really professional, you could arrange to have somebody constantly relay directions to you over the phone while you hike (they’d be able to see your position in relation to the GPS trail). In this case you’d want to bring several spare batteries as phone calls are obviously quite battery draining.

In addition to your phone, a compass is useful for navigation and will keep you going in the right general direction, even if you are unable to obtain a physical map of the route. We didn’t use our compass but if our phone had run out of juice we at least still had it as a backup navigational aid to help us get down off the mountain.

What we experienced was that there are various points along this trail where you will definitely get confused and be in doubt as to where to go next. Points where the trail forks into two or three paths, river crossings, rocky areas and open forest clearings are places where it can be tricky to find the continuation of the trail.

In these scenarios, trial and error is the best method to figure out the correct trail because you’ll realize soon enough if you’ve gone the wrong way if either the trail becomes totally unnavigable (i.e becomes dangerously steep or runs into impenetrable vegetation) or you start to stray unreasonably far away from the GPS track.

Check your phone regularly to spot mistakes sooner rather than later and in general, you should try to stick as closely to the GPS track as possible. However, you should also know that the GPS can sometimes be out by up to 4 metres or possibly slightly more in some cases, so don’t be afraid to stray from it slightly when the situation calls for it.

Your feet need attention

Since the terrain is very challenging and the hike very long, a good pair of reliable hiking shoes is a must. Even with good shoes however, blisters are a very real possibility and we started to develop a few pretty painful hotspots on our feet during the descent. To help prevent them and also deal with developing blisters here are a few tips:

- Wear two layers of socks or thicker socks. More breathable sock fabrics like nylon or special wicking socks are a better choice than cotton.

- Make sure your hiking shoes are a perfect fit for your feet, are well broken in and also tie up the laces reasonably tightly to minimize movement within the shoe

- Try wrapping your feet in duct tape or bandages

- Try lubricating your feet with powders or creams to reduce friction and allow sliding as opposed to rubbing

Dangerous wild animals are a possibility

One of the most memorable moments of our hike was an encounter with two feral water buffaloes. These are not at all like the domesticated kind that you find pulling ploughs in the rice fields below, being much more fearful of humans and far more aggressive.

The encounter occurred when we were on a flattish ridge section of the trail and as we rounded a bend, one of the two buffaloes came into view. The beast was looking at us intently, perched on a nice vantage point just three vertical metres or so above the trail.

As we drew close, the buffalo started blowing air and snorting out of his nostrils, which we interpreted as a sign of aggression and which brought us to an abrupt halt.

The enormous beast then made a sudden movement and we jumped backwards instinctively, thinking he was going to charge at us, but he darted off, along with his companion just nearby, crossing the trail in front of us and vanishing into a dense bamboo thicket beside the trail.

Apparantly, these feral buffaloes were more afraid of us than we were of them.

We have also read reports of people encountering wild boar along the trail, (which usually scamper away as soon as they see you), wild horses and even snakes, some of which could potentially be poisonous. Be vigilant for these animal threats when hiking the trails and never corner a wild animal; by denying the animal an escape route it will be forced to charge you.

Insect pests may be a problem

We expected to run into leeches while passing through the dense wet vegetation along the trail but didn’t encounter any. It’s still probably no harm to take some precautions against leeches though.

The usual measures are tucking your trousers into your socks and your sleeves into your gloves, rubbing your shoes, socks and lower pants with salt, wood ash or tobacco and rubbing citronella balm or other anti-leech ointments into your skin, especially around your ankles and feet. You can also carry a small bottle of brine or sea water to squirt on the leeches and dislodge them.

Some people wear special anti-leech socks because very small leeches can still pass through the weave of ordinary socks in some places. However, these are only necessary for terrain where these type of leeches are a real menace and probably won’t be necessary when climbing Fansipan.

Mosquitoes can reportedly be a problem at some times of the year, although when we climbed in January there were none. You should probably bring mosquito repellent and try to stay covered up if you’re climbing in the summer months.

What to wear

As you climb higher and higher, the temperatures do noticeably drop although you may not notice it much while you’re hiking due to your increased body temperature.

The temperature at the summit is about 10 degrees cooler than in Sapa and when we did the hike in mid-January, it was around -2 or -3 degrees Celcius when we reached the summit with significant added wind chill.

For your upper body, you should wear a thermal wicking base layer and two more layers on top of that, with the outermost layer being something reasonably thick and warm for the summit. Bring a warm hat and scarf also and a windshield jacket to help shield your body from the strong chilling winds just below and at the summit. Gloves aren't a bad idea either, not only to keep your hands warm near the peak but also because you'll be grabbing onto cold metal ladders, rocks, tree roots and bushes during parts of the hike.

For the lower body, take a pair of warm and sturdy hiking pants that won’t rip easily, as there are lots of thorny plants along the trail. Zip pockets are good for keeping your phone or compass handy for navigation.

A good poncho and perhaps an umbrella are also important in case it rains. Make sure the poncho is large enough to cover your backpack to afford extra protection to the contents. Do try to keep an eye on the weather forecast though and try to go on a day when there’s a very low chance of precipitation.

What to pack

It’s really critical to bring sufficient supplies of food and water for this route because it's energy-intensive and you'll dehydrate quite rapidly from all the exertion on the steep parts.

As regards water, there are a few streams and seepages along the way but not as many as we would have liked to see, since much of the time we were hiking along spurs and ridges. We easily consumed 3-4 litres per person during the hike so we would therefore advise you to bring that much and if you run out don’t worry, because you’ll find a refill point long before you get truly into the danger zone of dehydration. Do be aware however that we didn't find any places to refill during the final steep 1,000 metre ascent to the summit (part 2 in our description of the hike below).

For food, take plenty of sugary and high-energy foods because it’s a really energy-demanding hike due to the steepness and very high altitude gain. Chocolate bars, cake, honey, cookies, bananas and dried fruits are all good for a quick burst of energy when needed. You can also take other foods that release energy more slowly like pre-boiled eggs and various pre-cooked foods from the barbecue night stalls in Sapa like sweet potatoes, pork skewers, com lam (sticky rice cooked in bamboo) etc.

Since you'll be descending in the dark, a headlamp is a pretty essential item, unless you have enough spare batteries for your phone to use the in-built flashlight on that for several hours during the descent. However, a headlamp is still better because it's handsfree.

Going down the Tram Ton trail at night without a light source would be suicidal because heavy fog and cloud cover mean that you won’t always have the aid of the moonlight and even if you do, there are many stretches that pass through thick forest where you won’t be able to see a thing, even if the moon is still shining brightly. Make sure you bring a set of spare batteries for the headlamp too.

A basic first-aid kit is definitely a good idea, although we took our chances and didn't bring one. You’ll inevitably get a bit scratched up from thorny plants during the hike and you may also need to deal with blisters, sprains etc. Bee stings may also be a possibility as we did encounter one stretch along a ridge where there were lots of bees flying around. Sunburn could be on the cards if you have reasonably fair skin or if you do the hike on a really sunny day.

A good smartphone is a must for this hike, as you already learned when we discussed its importance for navigation. We recommend you buy a Vietnamese SIM card so that you can make emergency calls and communicate with somebody you know if you happen to have an accident or get into trouble.

The number to call in Vietnam for first aid or an ambulance is 115. Memorize this number before you set out. The emergency numbers like 911, 112 and 999 probably won’t work in Vietnam but you can also try dialing other 3-digit numbers starting with 11_ until you get through to something useful.

Emergency camping gear is something we highly advise you bring. If you don’t have any there are plenty of shops in Sapa that sell camping equipment and it’s also possible to hire gear in the town. Although it will make your backpack a bit heavier and make the hike slightly more challenging, it could also save your life if you can’t complete the hike and have to spend the night on the mountain.

What if you sprain an ankle, get altitude sickness or just collapse from exhaustion before completing the hike? Then what? You’ll need a way to keep warm and dry until you can either be rescued or can recuperate the strength to complete the hike. At the very least bring a sheet of plastic/tarpaulin and a means to make fire. We brought a tarpaulin (3m x 3m), a hammock, a sleeping bag, a bivvy bag and a foam sleeping pad.

Spare clothes aren’t a bad idea at all, but it’s best to just bring spare socks, t-shirts and other lightweight items and try your best to keep the heavier clothing items like pants and warm jumpers out of the rain.

Finally, make sure the contents of your backpack are all protected from rain in the case of any downpours. You can place vulnerable items like sleeping bags, spare clothes, electronics and anything else you’ll need to keep dry inside plastic bags or ziplocks. Make sure also that you have a raincover for your backpack and as we’ve already mentioned, your poncho can also help cover the bag if it rains.

A summary of the Sin Chai route and our experience climbing Fansipan

Finding the beginning of the Sin Chai trail may be a little tricky for some of you so we will provide detailed instructions for how to find the trailhead.

The trail starts from Sin Chai village (Ban Xin Chai on google maps) and the best way to get to there is to hire a motorbike taxi from near the church in Sapa. Walking there will only waste energy before the long hike and hiring a motorcycle to reach the village is logistically impractical, because you won't be descending the mountain via the Sin Chai trail. By motorbike taxi we paid a total of 40,000 dong for the 4.6 km ride.

When you reach Sin Chai village, you will come to a junction where there is a small school just to the left hand side, while the main path continues heading on down to the right.

Ignore the left turn to the school and continue along the main path for a little while until you see a left turn after a wooden house.

Take this left turn down a winding path through rice terraces until it brings you to a long iron bridge crossing a river.

After the bridge take a left and you’ll see a building with two large concrete pools ahead. Go past this and continue past some more buildings and along a narrow laneway until you come out to an open area with some man-made weirs and pebble-filled streams.

You could easily get confused here but keep going in the same direction you were walking as you entered and pick up the trail directly across from you on the other side of the river.

You will see the 'Chris Tresize' waterfall to your right (according to the maps.me app) as you cross this part. The ascent begins steeply from here and you just have to follow the GPS trail as best you can from this point onwards.

Part one - A pleasant hike

We managed to keep to our GPS track for a little while here at the beginning but at some point not far beyond the trailhead it became apparent that we had lost the trail. After departing from the trail, we soon found ourselves climbing up extremely steep ground and having to battle our way through thick vegetation just to keep moving forwards.

We were beginning to grow worried but luckily enough, we soon emerged onto a very welcoming and very wide dirt trail (it felt like a highway in comparison to where we came from) and followed this straight up the mountain for a while. We made a small mistake at the end of this stretch by taking a left turn going along the flat when we should have taken the right turn going uphill but the mistake was quickly realized and corrected.

This right turn uphill continues for some time, mostly through thickets of young bamboo, and eventually brings you up out of the claustrophobic forest to a refreshing view of the higher peaks far in the distance and the valley below. Just ahead, you’ll walk up onto a beautiful ridge lined with young bamboo and continue along this for quite some time.

The vegetation is thinner up here and good views are possible from many points, so long as the mists have lifted. The ridge walk is mostly pretty flat apart or undulating except for the end where it descends down into the forest again. It was here that we had the encounter with the feral buffalo that we described earlier in the article.

The ridge walk was probably our favourite part of the hike in terms of scenic beauty although there was one thing about it that made us feel uneasy; the ridge ran very close to the cable car, and as we walked along it, we often felt very exposed and visible to the tourists inside the cars, especially at points where we lost our bamboo cover.

What if one of the tourists reported that they saw people hiking on mountain or if there was a ranger in one of the cars? We did our best to avoid being seen although we were very visible at some points along the ridge where the vegetation was non-existent.

We made our second wrong turn along this ridge walk section by going left instead of right at one point. We went down a long wooden ladder and then passed into a beautiful native forest (not secondary bamboo growth this time), but we quickly realized our mistake and backtracked to where we made the error. We almost immediately found the correct trail and proceeded on.

.jpg)

The ridge walk eventually ended by descending down into the forest, where we made a third error at a place where a very large tree had fallen across a gully. We had guessed that the trail might continue across the fallen tree but as we walked across the tree we quickly realized that the trail actually continued down along the gully.

We continued down from here through the forest and eventually reached the bottom of the slope, where the terrain became much flatter and we began to run into a few small streams, where we finally had a chance to refill our empty water bottles.

Not long after this we came to a sort of open clearing with low vegetation and were a little confused about which way to go. We followed the GPS track as best we could and it took us up through a wet gully that was thickly vegetated. When we emerged at the top of the gully, we soon found ourselves standing at a very large and charismatic tree, which must have been hundreds of years old.

We could hear human voices from a campsite just off to our right and we had in fact reached a junction marked on our GPS trail. It was not a junction with the main Tram Ton trail but rather with a side trail that branches off the main Tram Ton trail.

We stopped for lunch at this old tree, using its thick roots as a backrest and it was just near here that we also spotted an interesting tree that bad been labeled. “Huodendron Tibeticum’’ the sign read. This evergreen tree had an unusual kind of smooth bark and there were a few of them scattered around this area.

Moving on from here we began to fear that we might run into people, having heard the voices nearby, but our fears soon proved to be unfounded as the trail remained as wild and as deserted as ever. We descended a little and contoured along a steep valley until the trail brought us down to a creek strewn with hundreds of rocks and boulders.

.jpg)

This was to be the largest creek we would encounter on the hike at maybe 8-10 metres across and we had read an account online of this being another easy place for getting lost.

You have to make sure to turn right when you hit the water's edge and follow it upstream, hopping along rocks for a little while until you come to a point where you must make a left turn crossing the creek and head into some dense vegetation on the other side (the trail is totally overgrown here). You have to just really trust the GPS trail here to get onto the right path.

The trail now ascends a little and then starts to descend again, bringing you down into another valley with a much smaller river at the base of this one. You will notice two small wooden structures down below and will probably see a blue sheet of plastic draped across them.

We went right down to the river here and started following it downstream a little but realized quickly that we were making a mistake. We then looked across to the other side of the river at the towering slope that was almost impossibly steep to climb up and we figured it couldn’t possibly be the point of continuation of the trail.

We were puzzled for several minutes trying to figure out which way the trail had gone, until we re-read an online account of the route that we had saved to our phone and it told us we had to walk upstream along this stream for a while and turn left to cross it at some point. Aha!

You don’t therefore want to actually continue all the way down to the stream but instead you have to try to find a right turn before you reach it, which will lead you upstream for a few minutes, going parallel to the river.

The trail here going upstream is really overgrown and feels like it hasn’t been walked in years, but when you’ve gone far enough, there will be a place where you need to turn left off the trail and cross the stream by stepping over some boulders. This is what we consider to be the end of part one, the easy part of the hike.

Part 2 - Hell begins

You’re now at about 2,000 metres above sea level (give or take) and the real hike is now beginning on the other side of this stream. This final part is the most exhilarating and steepest stretch of the entire trek, and continues upwards for about 1,000 vertical metres to the cable car station.

The trail is quite overgrown in many parts and it’s still possible to lose it here (we lost it once). You’ll have to climb dubious wooden vertical ladders (some have large gaps due to broken rungs) and even one or two horizontal ladders.

You’ll also need to make your way up steep gullies and steep ridges, clinging onto tree roots, clutching at vegetation and working your leg muscles really hard to keep making progress. You'll probably want to put your good camera away at this point as we did and just take a few pictures with your phone instead because this section of the trail demands full concentration.

There are some very exposed ledges with sheer drops and unstable ground so be really careful during the climb and always try to keep as far back from the edge as possible. Never place too much faith in any one tree root, foothold or anchor point either.

After you’ve ascended this very arduous trail for about one hour or perhaps even longer, you’ll eventually reach a point where the trail passes directly underneath the cable car. The cars come so close here to the trail that you can literally see how many passengers are in each car. In our case the number was very few because it was getting late in the day.

We stalled here for a while, pondering whether we should chance getting spotted or wait until the light had faded more and possibly until the cable car stopped running for the day. However, from this point it was still another 1.5-2 hours to the summit and still very steep climbing. It would be dangerous to attempt the final push in the dark so we were leaning towards continuing on and chancing getting spotted.

It was then as we sat contemplating our next move, that we suddenly spotted a fellow hiker ascending quickly up the trail below us, completely in his own world with headphones in his ears.

We were really surprised, amazed even, to see another person hiking the disused Sin Chai trail like us and on the same day too. This was surely a rare event, if not a miracle. Had there been some kind of divine intervention in this to help us make the right decision?

We called out to him as he approached and started a conversation with him. ‘’Where are you from?’’ we first shouted down the trail to him. It turned out his name was Artz and he was from Lithuania. He wasn’t too concerned about the whole corrupt ranger issue and apparently hadn’t even heard about it. He encouraged us to press on because we still had a long way to go to the summit and it would soon be dark. A third opinion was all we needed and we decided to just go for it and forget about the cable car.

We then walked very cautiously past a seemingly empty prefab for construction workers and continued the steep ascent to the cable car station. At points along here we were just literally directly underneath the cable car but we pressed on regardless, not caring at this point. A mist was also coming in that was helping to obscure our view of the cars and their view of us.

Although fatigue was really starting to set in now, we were still doing pretty well at this point, steadily ascending the fairly steep slope, until the trail suddenly got a lot steeper and more treacherous, just as we were about to reach the cable car station.

We had come to the crux of the entire hike; an almost vertical rock face blocking our path, which we could only skirt around via a precariously thin ledge jutting out from the face of the rock. The only problem was in getting up onto this thin ledge, which was extremely exposed and doing so required a very risky and tricky manouevre.

Because there were three of us, we managed to figure out a strategy to safely get all of us and our backpacks up onto the ledge and back onto the trail beyond the slab of rock but in all honesty, it was the most intense and scariest point of the entire hike and had there been only two of us and had we never met the Lithuanian guy, we may well have failed to reach the summit.

Just a little way beyond this, we ran directly into the cable car station. It was dark at this point and visibility was really poor in the thick fog but the station was well lit and we could see that it was absolutely enormous; a monstrosity of a construction that completely obstructed the original Sin Chai route to the summit.

Strong, bone-chilling winds were buffeting us here at the station and at this point really needed all the warm clothes we had. We entered a little paved garden area in front of the station and turned left, trying to find a way around the station but we immediately came to a dead end. We then turned back, walking the other direction and made almost a full circle around the station but the trail to the summit was nowhere to be found. We soon realized that we were going to have to enter inside the station and head to the summit via the same artificially constructed stairway that the tourists taking the cable car were using.

This was the part where we were sure it was all over. As we stood outside, we could hear voices and clanging noises from construction workers inside the building. We weren’t completely sure if the cable car had fully stopped operating although it was already dark and we were assuming that everything had shut down for the night. Still, there was every chance that we’d run into the wrong person and get ourselves caught if we ventured inside. Nevertheless, we simply had to take our chances or we would never reach the summit.

We then just went for it and boldly entered the building, at first finding ourselves inside a large, empty unfurnished room. We then found a staircase and climbed up it, entering into the large main lobby area, which luckily for us, turned out to be completely devoid of people. The lights were still turned on here however so we quickly walked through the lobby, passing by the tourist turnstiles on our left and trying to find the doorway that would lead us to the base of the steps that led to the summit. We quickly found the correct door but feared it would be alarmed or locked. We took our chances and it was open. No alarm thankfully.

We quickly exited the building and climbed the first flight of steps onto a large flat platform area. Up here we found a map on a signboard, which showed we still had a little more to ascend to reach the peak and that we would be passing up concrete steps through an elaborate complex of ornate gateways, pagodas and Buddha images.

We started climbing the steps, passed through a large gateway and soon after we passed through some ticket checkpoints that were unmanned due to the late hour. The last few hundred concrete steps to the summit would have been trivially easy if we had been fresh but they were torturous for us, partly because of the thinning air and partly because we were also just totally exhausted from all the previous exertion. We had ascended almost 2,000 metres at this point! We read signs on the way up that warned tourists to take regular rest stops on their short climb to the top due to the low oxygen levels, which did seem a little bit of an over-exaggeration to us.

There was a small building just below the summit that we had to pass by very stealthily, as we could hear men’s voices coming from inside. We staggered up the final few steps and at first we didn’t even realize that we had reached the top until we saw that suddenly, it was not possible to go any higher! Here we were on the flat wooden summit deck and there it was, the rocky tip of the summit rising a few feet above the deck and the metal triangle-shaped summit marker that said ‘Fansipan 3134m’’.

We had made it at last. After the most arduous, dangerous and exhausting hike of our entire lives, we had finally reached the summit of Mt. Fansipan, the roof of Indochina. At that point in time, we were higher than any other person in Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, Laos, Myanmar, Singapore and peninsular Malaysia, both literally and figuratively. We were the happiest people in the world at that moment and so relieved that the ordeal was finally over.

.jpg)

We took a few photos in the dim light to capture the rare moment, although there was a heavy fog, which made it difficult to take a good picture even with the camera flash. The wind was also chilling us to the bone so we didn’t want to delay too long. As we began to descend the steps back to the cable car station, we were reminded that it was not over yet. Little did we realize that we would almost be defeated again on the way back down.

Part 3: The descent

Our first concern when coming back down was that the door to the cable car station would be locked and we would be trapped on this tourist runway to the summit, possibly having to spend the night in one of the vacant buildings we passed along the way.

That fear quickly proved to be unfounded however as one of the two doors was wide open. The main lobby area was again empty so we quickly walked through it, passing by a small room which had a man sitting inside, reading a newspaper. The door to the room had a narrow glass window built into it, meaning that the man inside could have seen us had he looked up from his paper!

We rushed past the door, hoping the man inside didn’t look up and turned left at what we thought was the stairs we came up but no! We had taken the wrong staircase by mistake and had to come back up, pass by that dangerous door again and this time we found the correct staircase that we came up by.

We then got the hell out of the station as quickly as possible and started heading back down the mountain via the same trail we came up. We had another concern at this point and that was that we had not been able to find the beginning of the Tram Ton Trail on our way up and so we were a little worried that our GPS was wrong about the location of the junction.

We switched on our headlamps and again tried faithfully following the GPS, carefully walking a little way back down the trail we came up and this time we were successful in finding the beginning of the Tram ton Trail. We then began the long and arduous descent in the darkness, using just our headlamps and sometimes our phones for light.

It was during this beginning part of the descent that we were almost again defeated by the mountain because the trail was undulating like a snake for several hundred metres, with many steep and challenging ascents, which we simply did not have the energy for. It was frustrating that we were still not finished with ascending, even though this was the way down!

We somehow managed to persevere by summoning all the willpower we had and finally we got past this torturous undulating section and from here it was pretty much all downhill with just a few insignificant uphill stretches now and again.

The Tram Ton trail is generally much wider, less treacherous and harder to lose than the Sin Chai trail but we were descending it at night so we still had to be really careful. There were two or three instances where we got a little confused and had to guess the continuation of the trail, but generally it was easy enough to follow.

The trail was also paved with steps and flat stones along many stretches, making it much easier to walk along and figure out the correct trail. There were metal handrails going down alongside many of the stairway sections and sturdy metal ladders at the really steep parts, as opposed to the dodgy wooden ladders on the Sin Chai trail.

A major concern while descending was the campsites. The Tram Ton trail has one campsite at 2,800m and another at 2,200m. As we approached the first camp at 2,800m, we could see the light from the camp glowing in the darkness just a few metres off to the right-hand side of the trail. We turned off our bright headlamps and tried to just use the dim light from our phones to illuminate the trail in front of us. It was a little risky to do this because the trail was quite steep and unpredictable but it was also risky to walk with bright headlamps and possibly get caught by rangers.

Just after this first campsite, our new Lithuanian friend was getting anxious to press on ahead because his girlfriend was becoming worried about him and he wanted to get back to Sapa as soon as possible. We said goodbye to him and let him go on ahead as we were taking our time anyway.

Further on, we arrived at the lower campsite and the fog had cleared at this point in time, meaning that we were able to use the light of the moon instead of our phones to help us see the trail. This campsite at 2,200m consisted of several large buildings, which had steeply-angled tin roofs and tin-walls.

The cabins glinted spookily in the pale moonlight and they lay on either side of the trail, meaning that we would have to walk right between them. We hesitated as we saw one of the buildings had an open door. Was there anybody inside? It didn’t seem like it so we just walked right through, treading as softly as we could. We soon had left the campsite far behind us, relieved not to have run into anybody.

At this point, we were clear of all the campsites and we just had to keep going on and on. Our feet started to ache at this point and we began to develop painful hotspots on our feet, which really slowed us down.

The way back really seemed never-ending and there were many more steep sections that we had to descend. At some point, we stopped descending and the trail became much flatter. We knew at this point that there wasn’t too much more ground to cover until we were back at the main road.

The trail continued like this for a long time and near the end, we walked through a beautiful wooded area alongside a stream and just kept going and going until finally at long last, we reached the national park entrance.

This was it. The final hurdle. Was there somebody here on night-duty, waiting to catch people like us coming off the mountain at night without a guide? We would soon find out.

As we walked out into the main parking area, we were greeted not by a person but by several dogs, which were lying on the ground outside the large building to our left. The dogs noticed us and began barking loudly enough to wake up a night watchman, had there been one sleeping there. One of the dogs was particularly bothered and came very close to us, barking at us constantly and very aggressively until we had exited the compound and walked out onto the main road.

We hobbled away down the road, disappearing into the fog with the dog barking behind us all the while and very soon managed to hitch a free ride with a night bus that was going to Sapa. Ironically enough, we drove past our Lithuanian friend who was seemingly attempting to walk the 14km all the way back to Sapa in the dark instead of hitching a ride like we did. So much for his intent to get back to the town quickly!

We were the happiest people in the world as the bus sped along the winding road through the fog towards Sapa. We had actually made it all the way to the summit and back without getting caught by rangers, without getting lost, without falling down a ravine to our deaths and without collapsing from sheer exhaustion.

We had accomplished something that should have been impossible but here we were, living proof that it was possible and that we had really done it. The reality of what we had just accomplished wouldn’t truly sink in for a few days.

For now, all we really cared about was getting to bed and sleeping for at least the next 14 hours. We awoke late the next day and almost every muscle in our bodies was aching and in particular we could feel the tenderness in our quadriceps and calves.

We could hardly walk down or up steps without wincing in agony for the next two days but we didn’t care. It was worth the punishment. We had climbed Fansipan for free, without a guide, by the hardest possible route and had miraculously avoided being caught by the corrupt park officials. It was an extraordinary victory for both of us and it was a memory that we would treasure forever.

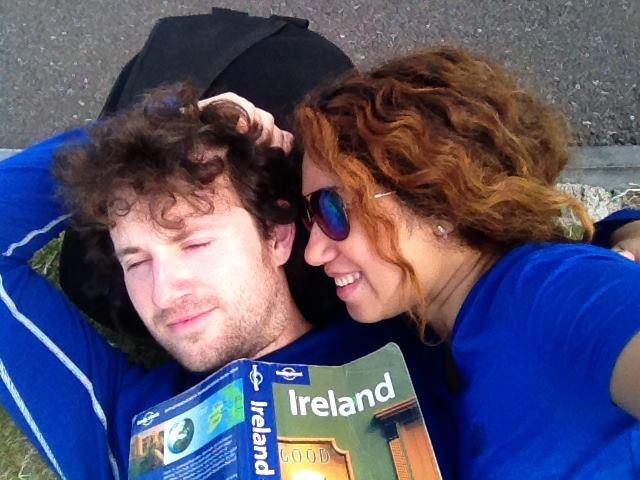

Recommended Guidebook: Lonely Planet Vietnam

Have you ever done something crazy like this? Tell us your story in the comment section below!

JOIN OUR LIST

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

ABOUT US

Our names are Eoghan and Jili and we hail from Ireland and India respectively.

We are two ardent shoestring budget adventure travellers and have been travelling throughout Asia continuously for the past few years.

Having accrued such a wealth of stories and knowledge from our extraordinary and transformative journey, our mission is now to share everything we've experienced and all of the lessons we've learned with our readers.

Do make sure to subscribe above in order to receive our free e-mail updates and exclusive travel tips & hints. If you would like to learn more about our story, philosophy and mission, please visit our about page.

Never stop travelling!

FOLLOW US ON FACEBOOK

FOLLOW US ON PINTEREST

-lw-scaled.png.png)