The Complete Guide To Preventing Mosquito Bites When Travelling (+ Must-Read FAQ)

From rats and cockroaches to fire ants and leeches, most travellers have to deal with annoying pests at some point or another in their journey.

But perhaps no pest is as widespread or as consistently problematic for travellers as the humble mosquito.

The mosquito undoubtedly reigns supreme as the most irritating insect pest that travellers face. So irritating that you’d probably throw a banquet if all the mosquitoes were to one day suddenly vanish off the face of the Earth without a trace.

These flying vampires are hellbent on sucking all the enjoyment out of your otherwise fairy-tale trip; it seems that no matter where you go, they’re there, repeatedly attacking your ankles, feet, legs and other exposed body parts in order to dine on your lifeblood.

The sneaky buggers are also highly adept at avoiding detection, flying in under the radar and then injecting saliva containing enzymes that act as a mild painkiller, so that often you don’t even register the attack until afterwards, when the bite starts to swell up and become itchy.

And that exasperating high-pitched whining sound that mosquitoes make as they hover around your ears while you’re trying to fall asleep in your bed at night? That’s almost as irritating as being made a meal of.

But it’s important to remember that mosquitoes are not merely an irritation or nuisance.

Despite their diminutive size, these airborne pests are anything but innocuous and, in fact, the most fitting word to describe them would perhaps be insidious.

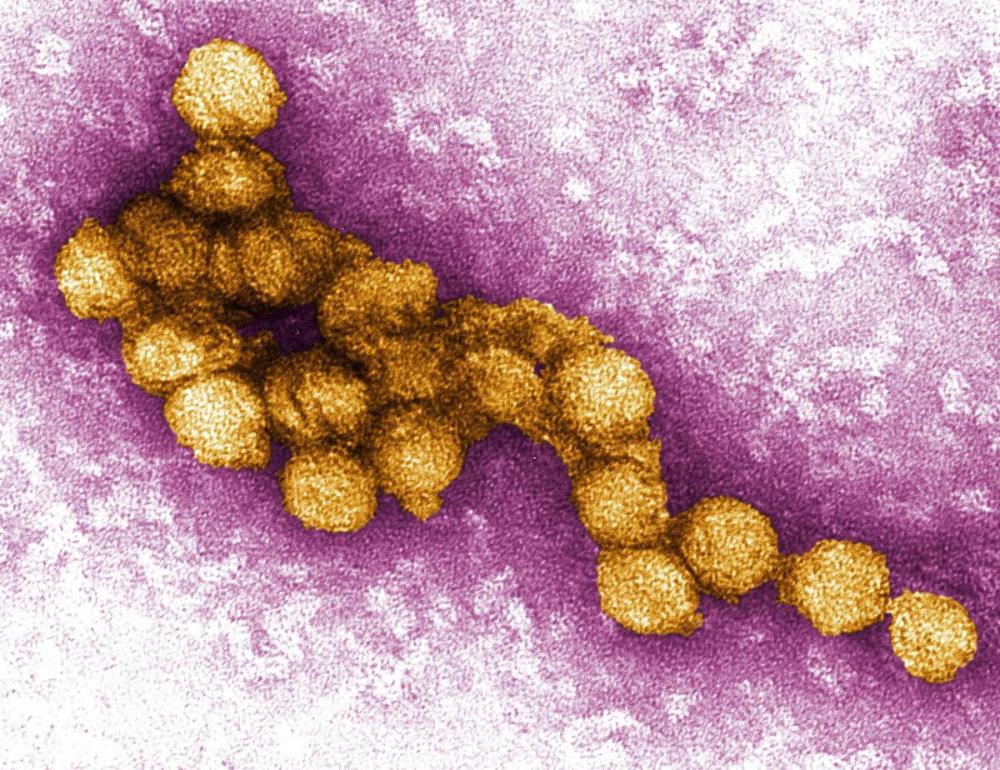

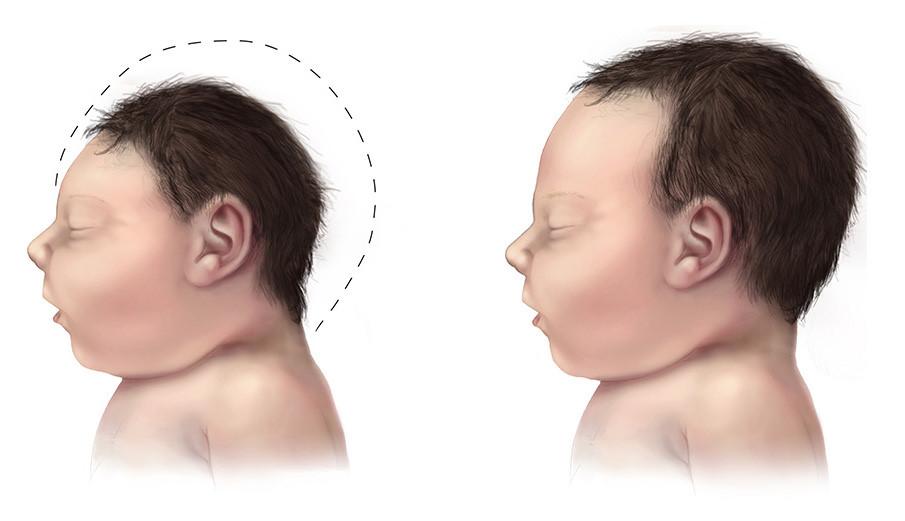

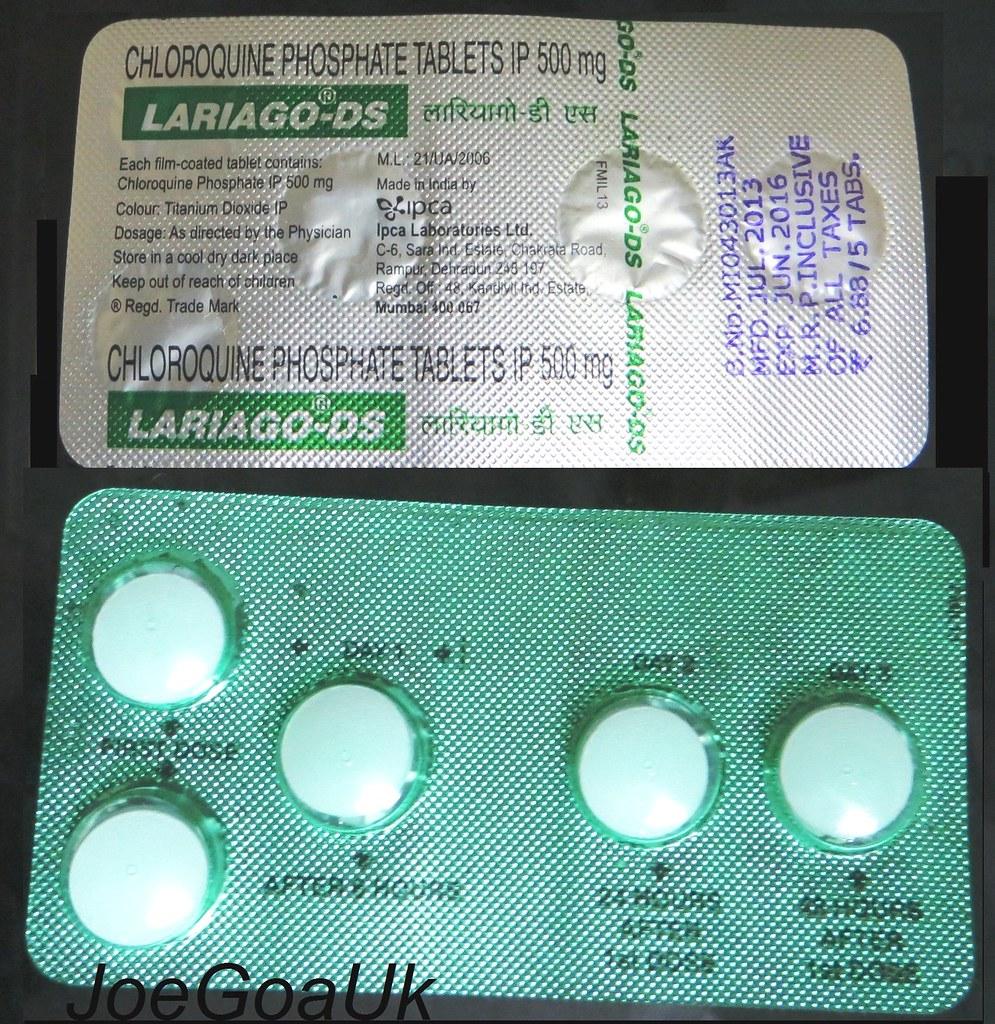

As you probably already know, mosquitoes are vectors for a multitude of dangerous diseases including malaria, dengue, West Nile Virus, Zika virus, chikungunya, yellow fever, filariasis, Japanese encephalitis and many others. Wikipedia has a longer list of them.

These diseases collectively result in approximately 2 million human deaths every year, exacting a significantly higher death toll than that of the second biggest man-killer - other humans - which by comparison only accounts for 475,0000 deaths annually.

In total since the dawn of time, it’s estimated that mosquitoes have taken the lives of some 52 billion people – more lives than have been lost in all the wars of history combined.

Mosquitoes have wiped out entire armies, contributed to the collapse of mighty empires and altered the course of the world’s fate on many occasions.

It’s even believed by some researchers that mosquitoes played a major role in the extinction of the dinosaurs.

Mosquitoes are quite literally the world’s deadliest animal and despite our best efforts at ridding the world of them, we have not yet won the war.

The mosquito's resilience partly stems from its extraordinary ability to genetically mutate and develop resistance against the insecticides we invent to annihilate it.

Unfortunately, there are no reliable vaccines or preventative treatments for the majority of mosquito-borne illnesses, which is why knowing how to keep mosquitoes at bay when you travel is crucial for your health and wellbeing, as well as for your sanity and peace of mind.

In this article we’re going to list and discuss the most effective and proven methods for keeping mosquitoes away and avoiding their bites when you're on the road.

After you’ve read through the solutions, keep reading, as we’ve included a bonus FAQ section in the second part of the article to answer all your most pressing questions about mosquitoes and travel.

The FAQ includes advice on antimalarial medications, mosquito-borne illnesses, vaccinations, treatments for bites and much more!

Table of contents

- How to keep mosquitoes away when travelling

- Practical tips for avoiding mosquito bites

- Products that repel mosquitoes

- Spatial vs topical repellents

- Topical repellents

- Spatial repellents

- How to keep mosquitoes away while at your hotel

- Mosquitoes & travelling FAQ - all your questions answered

- What are mosquitoes?

- How long have mosquitoes been around?

- What is the mosquito life cycle?

- What do mosquitoes feed on?

- When and where are mosquitoes most active?

- How do mosquitoes detect your presence?

- Where do mosquitoes prefer to bite people and why?

- How exactly do mosquitoes bite you?

- How to reduce the itching and swelling caused by mosquito bites?

- Is every traveller equally susceptible to being bitten by mosquitoes?

- What diseases can travellers contract from mosquitoes?

- Are mosquito-borne illnesses vaccine-preventable?

- When should travellers take antimalarials and which drugs are best to take?

- Conclusion

There is a host of strategies that you can employ as a traveller to minimize contact with mosquitoes, hence preserving your sanity and reducing the risk of contracting a mosquito-borne illness.

We’ll cover some easy practical tips, the best products for repelling mosquitoes and lastly we’ll go over how to avoid mosquito bites at your accommodation (where you can’t simply go somewhere else).

#1 - Cover up (with the right clothing) any exposed skin during peak mosquito feeding hours

In tropical and subtropical climes where mosquitoes can be a menace, it’s natural to spend most of your time going around in a t-shirt, shorts and sandals because of the intense heat and humidity.

Such attire makes perfect sense until it’s that time of day when the mosquitoes come out to feed, at which point you suddenly find yourself wide open to attack.

The simple solution is to just cover up the exposed skin on your neck, torso, arms, legs, hands and feet during the hours when mosquitoes come out to feast.

We go into more detail about mosquito feeding hours in the FAQ section below, but basically, most species tend be at their most active at dusk and dawn.

These also conveniently happen to be the coolest hours of the day when you might be feeling a little chilly and thinking about donning a long-sleeved shirt or a pair of long pants anyway.

When covering up to prevent mosquito bites, your clothes should be loose fitting, because mosquitoes can still easily bite through a piece of fabric that’s stretched tight against your skin.

You might want to tuck your shirt into your pants and your pants into your socks too so that you have no chinks in your armour for the mosquitoes to exploit.

Make sure to ditch the sandals too and wear a reasonably thick pair of socks with a pair of shoes instead, as some species of mosquitoes love feet and ankles, and are capable of biting through thin socks.

As regards clothing colour, some sources will claim that bright colours are more attractive to mosquitoes, but the majority say that you should avoid wearing dark colours.

If it is true, it may be because dark clothing absorbs radiates more heat than light clothing, which mosquitoes are sensitive to.

The main thing is that you get into the habit of wearing your mosquito-proof outfit whenever you’re getting up at dawn or heading out in the evenings.

#2 - Avoid entering shaded, sheltered areas

During the hottest hours of the day mosquitoes will retreat to the cover of trees and other shady, sheltered areas where the sun doesn’t penetrate and where the air is relatively still.

They prefer these shaded, windless refuges to avoid death by dehydration in the heat of the sun and also because they are poor pilots in high winds, as anyone that has used an electric fan on high speed to blow them away will attest to.

On hot sunny days in the tropics many travellers will have experienced the sudden barrage of mosquito attacks the moment they stepped out of the harsh sun into the shade of trees in order to cool off.

If you must be near trees, always try to stick to the transition zones or forest edges, where there is more sunlight and the chance that a breeze might be blowing to keep the bugs away.

#3 - Ditch the floral-scented soaps, body washes, deodorants and perfumes

I get it; some travellers don’t want to smell like garbage during their trip. But mosquitoes are attracted to the strong scents of the various personal care products that many travellers apply to their bodies.

Perhaps this is because mosquitoes confuse these fragrances with those of flowers, from which they extract nectar as their primary food source.

In any case, if you want to avoid becoming a magnet for mosquitoes, lay off the smelly stuff and try to use more neutral-smelling products that don’t leave a lingering fragrance on your skin.

#4 - Take regular showers and keep your clothing clean

The logic here is pretty simple; mosquitoes are attracted to compounds in human sweat, so by showering frequently and washing your clothes regularly, you get rid of the lactic acid and other compounds found in human sweat that mosquitoes find appealing.

There will be times during a trip when you just don’t want to cover up your exposed skin, and it's virtually impossible to always avoid entering into mosquito habitats during your daily escapades.

To remain protected at all times, you need to employ some kind of a mosquito repellent - something that actively deters mosquitoes from landing on you or entering your personal space.

Mosquito repellents normally fall into one of two categories – spatial repellents and topical repellents.

Topical repellents are the various creams, balms, lotions and liquid sprays that are applied directly to the skin to discourage mosquitoes and other biting insects from landing on you.

Spatial repellents on the other hand work by creating a protective "cloud" around you that is filled with mosquito-repelling substances like smoke, volatile components of essential oils and pyrethroids. Such compounds are hazardous to mosquitoes and impel them to flee the scene.

Both types of repellents can come in portable forms and can provide protection from bugs no matter where you are, although topical repellents are generally more suitable for when you're out and about, while spatial repellents tend to be better for keeping mosquitoes out of your hotel room.

One of the downsides with topical repellents is that they gradually wear off and have to be re-applied every so often (usually every 6 hours or so). They can also make your skin oily and some products can carry a strong, unpleasant smell.

Spatial repellents can also have some issues, as we shall soon see in more detail. Some types can depend on having electricity, while others can make a room not only hostile to mosquitoes but also to their human occupants.

We'll first look more closely at topical repellents, which are based on one or more of the following active ingredients that have been demonstrated to be effective mosquito deterrents.

#1 - DEET

Chemical formula: C12H17NO

In terms of sheer mosquito-repelling efficacy, it’s pretty hard to beat DEET, which is an acronym for N, N-Diethyl-3-methylbenzamide (also N, N-Diethyl-meta-toluamide), a slightly yellowish, almost colourless liquid that endured as the undisputed champion of mosquito repellents for several decades.

DEET was originally developed for the U.S. army in 1944 by a chemist named Samuel Gertier, who was working with the USDA (United States Department of Agriculture) at the time.

The development of DEET was a reaction to the US army’s harrowing experience of jungle warfare during World War II, following which a need was recognized to better protect soldiers in mosquito-infested jungle environments.

After being initially tested as a pesticide on farms, DEET was adopted by the US military in 1946, but it wasn’t until 1957 that it became available to civilians.

The exact mechanism by which DEET repels mosquitoes is still not clearly understood and has caused much debate among scientists.

The most likely explanation is that DEET confuses the insects by changing the way that their olfactory nerves (located on the mosquito’s antennae) respond to 1-octen-3-ol, an alcohol found in human breath that alerts mosquitoes to our presence.

When DEET disrupts the normal response pattern of these olfactory nerves to 1-octen-3-ol, the mosquito can still smell something, but it isn’t quite sure what, so it leaves us alone.

An important consideration when choosing a DEET-based topical repellent is its concentration, which can range widely from 4% to 100%.

In general, the higher the DEET concentration, the more hours of protection the repellent will provide before its effects wear off, although the concentration has little impact on the repellency strength.

Many experts suggest a concentration of 25-30% DEET as optimal, which should provide around 6 hours of protection in most cases, while formulations with 100% DEET will often claim to provide up to 12 hours of protection.

If you only need 1 or 2 hours of protection, you can use a repellent with a DEET concentration below 10%. Some products also use a "slow-release" formula, which can extend the duration of their effectiveness beyond the usual number of hours.

There have been some health concerns regarding the use of DEET. You definitely don’t want to ingest, directly inhale or get the stuff in your eyes. In rare cases DEET can even cause rashes, irritation and swelling of the skin with regular use.

DEET is not recommended at all for infants that are younger than 2 months old and for infants older than 2 months only the lowest concentrations are safe to use.

DEEt should never be applied to children’s hands as they could accidentally rub the chemical into their eyes or ingest when handling food.

Studies have shown that DEET applied to the skin gets absorbed into the bloodstream, where it gets broken down by the liver and is almost completely eliminated from the body via the urine within 24 hours.

DEET has some other notable drawbacks, such as its ability to dissolve certain plastics, such as those found in sunglasses, the lenses of eyeglasses and watch crystals (the protective transparent covers that protect watch faces). Keep the stuff away from your glasses and watch!

DEET can also damage certain synthetic fabrics such as rayon and spandex, (though it has no effect on cotton, wool or nylon) and it has a distinctive odour that many people can’t stand.

The bottom line is that DEET one of the most effective and popular (some 30% of the U.S population uses it) topical repellents on the market and is used by millions of people every year.

One of the most popular DEET-based repellents on the market is Repel® Insect Repellent Sportsmen Max Formula.

This is a 40% DEET formula in a pump spray bottle that was developed for outdoor enthusiasts and sportspeople who become bug magnets when they start perspiring. The relatively high concentration (40%) of DEET in this formula ensures long-lasting protection from mosquitoes and other bugs.

However, being the potent man-made chemical that it is, DEET doesn’t sit well with everyone. This has led to some people steering clear of DEET-based repellents and opting to use alternatives like the ones we discuss below.

#2 - Picaridin

Chemical formula: C12H23NO3

For over 50 years since it was first developed, DEET enjoyed its reign as the matchless top dog of mosquito repellents.

That was, until a synthetic compound called picaridin was developed by the German pharmaceutical giant Bayer AG in the 1980s. By 1998 it had entered the European and Australian consumer markets by 2005 it had reached the U.S.

Picaridin (also known as icaridin, Bayrepel and KBR 3023) is an odourless, colourless liquid that is based on a natural compound called piperine, which was first isolated in 1819 by Hans Christen Orsted from Piper nigrum, the fruits of which plant become the black and white peppercorns that we use for seasoning our food.

Like DEET, picaridin works as an effective mosquito and general insect repellent, also providing protection against black flies and especially midges (no-see-ums), though DEET is believed to be more effective at deterring ticks.

Unlike DEET, picaridin has no distinctive odour, its preparations don’t leave the skin feeling oily and it won’t dissolve plastics and other synthetic materials.

As with DEET, concentration influences the length of time that picaradin-based repellents will remain effective for. Although concentrations can range from 4% to 100% with DEET, with picaridin they generally range from 7% to 20%.

A low 7% picaridin concentration is roughly equivalent to 10% DEET, while a high 20% provides the same 4-5 hours of mosquito protection as the equivalent concentration of DEET.

As regards health consequences, not a great deal is known about the long-term effects of picaridin as it has only been on the consumer market since 1998.

A small amount of picaridin (less than 6%) is absorbed through the skin when applied and it is broken down and then excreted by the body like DEET after this occurs.

Another consequence of being a relative newcomer to the market is that Picaridin is still only used in a limited number of insect repellent products, although that is slowly changing.

For a Picaridin-based repellent, try Ranger Ready Repellent. This orange-and-bergamot-scented 20% picaridin formulation(orange scented) comes in a small mist spray bottle and can be applied directly to skin, clothing and gear for 8-12 hours of protection against mosquitoes, fleas, midges (no see ums), ticks etc.

#3 - IR3535 (3-[N-butyl-N-acetyl]-aminopropionic acid)

Another potent synthetic bug repellent and one of the big four (DEET, picaridin, IR3535 and oil of lemon eucalyptus), IR3535 or EBAAP was developed in the early 1970’s from a natural amino acid called β-alanine, by the American pharmaceutical giant Merck & Co Inc. Its full chemical name is a mouthful – ethyl butylacetylaminopropionate.

Although it has been marketed in Europe since the mid 70’s, IR3535 was only introduced into the U.S market in 1999, so it’s a latecomer to the new world. It’s commonly used in sunscreens and mosquito repellents, and is currently found in about 150 products worldwide.

Depending on the species of mosquito in question, IR3535 has been shown to be equally or slightly less effective at repelling mosquitoes when compared with DEET and picaridin.

A few studies have shown the chemical to be very effective against ticks. One study found IR3535 to be twice as potent as DEET at repelling nymphal deer ticks (Ixodes scapularis).

The recommended formulation for combatting ticks and mosquitoes is generally 10 to 30 percent IR3535.

As regards safety, IR3535 has a pretty spotless record and European authorities have received few if any complaints about adverse effects caused by the chemical, although it can be irritating to the eyes, and it may also damage or dissolve plastics.

Overall, this is a mosquito repellent to be reckoned with, and will be especially advantageous in situations where dangerous lyme-disease-transmitting ticks are also on the cards.

#4 - Oil of lemon eucalyptus

Crude lemon eucalyptus essential oil is obtained by steam distilling the dried leaves and twigs of Corymbia citriodora, the Australian lemon eucalyptus tree.

Unfortunately this essential oil’s life as a repellent is fleeting (approximately 1 hour) due to the volatile nature of its mosquito-repelling constituents.

However, one component present in the unrefined oil in small quantities is PMD (p-menthane 3,8 diol), which is a very effective and long lasting mosquito repellent.

By increasing the amount of PMD from 1 to 65 percent while also reducing the citronellal content of lemon eucalyptus essential oil, you get a refined product known as oil of lemon eucalyptus (OLE), which is a much longer lasting and more effective mosquito repellent than the unprocessed oil.

In fact, OLE is the only mosquito repellent derived from a natural essential oil that’s registered with the EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) and that’s endorsed as safe and effective by the CDC (Centres for Disease Control and Prevention). It's one of the "big four" that we mentioned earlier.

OLE ranks right up there with conventional synthetic repellents like DEET and Picaradin, and with other highly rated “biopesticide repellents” like IR3535 and 2-undecanone.

#5 - Natural topical repellents

Many people prefer to use organic mosquito repellents to avoid the potentially adverse effects that synthetic repellents may have on their health, their children’s health and on the environment.

The good news is that repellents based on natural essential oils can be very effective against mosquitoes, some even more so than their synthetic counterparts.

The bad news is that compared to synthetic repellents, the effectiveness of essential oils tends to be short-lived because the constituents in them that deter mosquitoes are quick to evaporate from the skin.

But if you’re happy to keep re-applying the essential oil every 1-2 hours (more frequent applications are required if you're sweating or going in the water) then you can maintain pretty decent protection against mosquitoes and other bugs.

It’s very important to note that many essential oils are only effective as mosquito repellents when undiluted or weakly diluted.

Rather problematically though, some essential oils can cause skin irritation and dermatitis in certain people, especially when used at high concentrations.

Some undiluted or weakly diluted essential oils will also give off a very overpowering fragrance that certain people may be unable to tolerate.

For these reasons it’s usually best to use essential oils with a carrier oil (also known as a base oil) and you might also want to do a patch test on a small area of skin to see if you’re sensitive to a particular oil before applying it over a larger area of your body.

For oils that must be used at high concentrations to achieve good repellency, it may be a good idea to wash them off the skin soon after use.

Another thing to watch out for with essential oils is photosensitization, which is where the applied oil causes your skin to become more susceptible to UV rays and hence sunburn.

Photosensitizing agents are typically present in citrus oils like bitter orange, lemon, lime, tangerine, grapefruit and bergamot oils, although the effect can be somewhat negated by diluting the oil.

Essential oils can be bought online in their pure form and diluted with water or a carrier oil as desired. These homemade mosquito repellents can be applied topically or used in a spray bottle as a room spray.

Essential oils can also be blended with other essential oils to improve repellency. Commercial mosquito repellents are also available that are based on one or a combination of different essential oils.

What follows is a brief summary of the essential oils that have shown the most promise as mosquito repellents. It’s not an exhaustive list and there is still much more experimentation to be done in this field by scientists.

You should also experiment yourself and test other essential oils to see what works best for you. There are approximately 150 commercially important essential oils to begin experimenting with and in total there are over 3,000 essential oils known to mankind.

Eucalyptus oil

Considered to be one of the most effective natural mosquito repellents, eucalyptus oil is obtained by steam distillation of the leaves of certain species of eucalyptus.

Most of the world’s eucalyptus oil is produced from the Australian species, Eucalyptus globulus (Southern Blue Gum).

Even just heating Eucalyptus leaves will release certain volatile compounds into the air that will discourage mosquitoes from entering the space.

Try Artizen Eucalyptus Essential Oil (100% pure and undiluted).

Citronella oil

Citronella oil is extracted by steam distillation of the leaves and stems of a number of species in the Cymbopogon (lemongrass) genus, which is widespread throughout the tropics and sub-tropics.

Most of the world’s citronella oil is produced in China and Indonesia, though several other countries also contribute to global production.

There are two chemotypes of citronella oil; the Java type, (obtained from Cymbopogon winteranius) and the Ceylon type (from Cymbobogon nardus).

This essental oil has over 80 constituents, though the 3 most important ones are citronellal, geranial and limonene. Some studies have found it to be the most effective essential oil for repelling mosquitoes.

Try Organic Citronella Essential Oil (100% pure and undiluted) by Healing Solutions.

Similar to citronella oil is lemongrass oil, which comes from Cymbobogon citrata and has similar insect-repelling properties.

Confused about the difference between lemongrass and citronella?

One major difference between the two plants is that lemongrass is often used as a flavour-imparting herb in Asian cooking or in herbal teas, whereas citronella is not considered fit for human consumption.

Catnip (nepetalactone) oil

Nepetalactone oil is obtained by steam distillation of the leaves, stems and flowers of the European native herb Nepeta cataria (commonly known as catnip or catmint), which is a member of the mint family.

In a study carried out by Iowa State University research group researchers came to the conclusion that nepetalactone oil was ten times more effective than DEET at repelling mosquitoes.

Try Catnip Essential Oil (100% pure and undiluted) by Plant Therapy.

Peppermint oil

Peppermint oil is distilled from the leaves and flowers of the hybrid peppermint plant Mentha x piperata, a native of Europe and the Middle East that is a cross between Mentha aquatic (water mint) and Mentha spicata (spearmint).

This essential oil is a general insecticide and one study demonstrated that 100% of Culex quinquefasciatus mosquito larvae had died within 24 hours of being placed in water that a few mililitres of peppermint oil had been added to.

Try Cliganic Organic Peppermint Oil (100% pure and undiluted), which is certified by the USDA.

Cinnamon oil

The aromatic spice that most of us call cinnamon is simply the dried inner bark of various evergreen tree species in the genus Cinnamomum, which is found in Southeast Asia, China, Australia and even in Africa.

To prepare the spice, the larger sheets of cinnamon bark are dried and ground into cinnamon powder while bark peeled from the smaller twigs and shoots is kept whole, curling as it dries to become the familiar rolled sticks or quills of cinnamon.

Cinnamomum verum (Ceylon cinnamon) is the “true” cinnamon and most of it comes from trees grown in Sri Lanka.

C. verum is of a higher quality than Cinnamomum cassia (Chinese cinnamon), which is the cheaper, more strongly flavoured, most commonly consumed variety that dominates the supermarkets.

The majority of the world’s Cinnamomum cassia supply comes from Sumatra’s Kerinci valley, with the rest coming from China, Vietnam and Burma.

Cinnamon essential oil is usually extracted by cold-pressing or steam distillation of the bark and leaves of cinnamon trees, with the oil extracted from the bark usually being slightly costlier due to the greater difficulty involved in extraction.

One study conducted at the National Taiwan University found four compounds in cinnamon essential oil to be effective at killing the emerging larvae of the yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti, although the oil was not tested on adult mosquitoes.

Try Organic Cassia Cinnamon Essential Oil (100% pure and undiluted) by Healing Solutions.

Clove oil

Clove oil is steam distilled from cloves, which are the dried, aromatic, unopened flower buds of Syzgium aromaticum, an evergreen tree in the Myrtle family that is native to the Maluku islands of Indonesia but which is now widely cultivated throughout the tropics.

Indonesia is the world’s largest producer of cloves and clove oil by far, with Madagascar and Tanzania trailing far behind.

In one study, clove oil was found to provide 100% protection against three species of mosquito for longer than the 38 other essential oils that were tested.

Try Artizen Clove Essential Oil (100% pure and undiluted).

Thyme oil

Another potent mosquito repellent, thyme oil is steam distilled from the leaves and flowers of Thymus vulgaris (common thyme) or Thymus zygis, two herbs that belong to the mint family and are native to Southern Europe.

The thyme oil produced in Spain or Turkey comes from T.zygis whereas that produced in France and other countries is derived from T.vulgaris.

One study that compared 5 different essential oils found thyme oil (along with clove oil) to be the most effective at repelling mosquitoes, providing 1.5 to 3.5 hours of protection depending on the concentration.

Try Thyme Essential Oil by Healing Solutions (100% pure and undiluted), which is thyme oil extracted from T.zygis. It comes in a Euro-dropper bottle for convenience.

Patchouli Oil

This essential oil is steam distilled from the dried leaves of Pogostemon cablin, a herb (belonging to the mint family) whose origin is shrouded in mystery, but is now cultivated widely throughout the tropics.

Although many countries produce patchouli oil, Indonesia is by far the world's greatest supplier, accounting for over 90% of global production.

In the previously mentioned study that compared the mosquito repellency of 38 essential oils, patchouli was one of the three oils that were deemed to be the most effective out of all 38 that were tested.

Try Artizen Patchouli Essential Oil (100% pure and undiluted).

Neem oil

Neem essential oil is extracted from the fruits and seed kernels of Azadirachta indica (neem tree), which is endemic to the Indian subcontinent but has since been introduced to other parts of the tropics.

Indian people have long known about the tree’s anti-fungal, anti-bacterial, anti-inflammatory and anti-aging properties.

The leaves of neem have been burned to ward off insects and the seed kernels contain an extremely potent growth-inhibiting compound called azadirachtin, which disrupts the feeding, growth and reproductive processes in many types of insects that are exposed to it.

Unfortunately, there’s a paucity of reliable studies on Neem essential oil as a mosquito repellent and experiments have shown mixed results.

However, one recent studythat was carried out in an Ethiopian village found Neem oil to provide 70% protection for 3 hours against the Anopheles arabiensis mosquito, the principal malaria vector in Ethiopia.

During the same study, DEET and MyggA (another commercially available repellent) were observed to have provided over 96% protection for an average time of 8 hours.

Try Milania Neem Oil. It’s organic, cold-pressed and 100% pure and undiluted.

#6 - Permethrin

Chemical formula: C21H20Cl2O3

Permethrin is a synthetic contact insecticide (belonging to the pyrethroid family) that was invented in 1972 by a British chemist named Michael Elliot.

Permethrin is a pyrethroid - pyrethroids are synthetic analogues of pyrethrins, a class of naturally occurring insecticidal organic compounds that are normally derived from the flowers of the Chrysanthemum plant, Chrysanthemum cinerariifolium.

Permethrin was one of the world’s first agriculturally viable insecticides and is still used in many countries to that end today, although it was banned for agricultural use in the EU in 2003. India is currently one of the world’s largest producers and exporters of the chemical.

Permethrin has a long history of use in the military and is still used to treat the uniforms and bed nets of soldiers of the British and US armies to give protection against mosquitoes, ticks, ants, mites and other biting insects. It is only since 2003 however that permethrin-treated clothing has been available to civilians.

Although permethrin can be used topically at high concentrations to treat scabies and head lice (usually sold over the counter under the names Nix and Elimite for this purpose), as a mosquito repellent it is never applied directly to the skin and is only used to treat clothing and other equipment.

Clothing (outerwear only, not underwear), shoes, backpacks, hats, mosquito head nets, bed nets, camping gear (tents, tarps, bivvy bags etc.) and other such items can all be impregnated with permethrin to make them repel mosquitoes and other insects.

In fact, clothing and gear that has been impregnated with permethrin will not only repel mosquitoes but may also kill or incapacitate them on contact, the latter effect being known as a “knock-down”.

Once properly treated with permethrin, clothing, gear and nets will retain their repellency even after going through the wash several times (you should hand wash or use a gentle cycle in the washing machine to help preserve effectiveness for longer).

So how does a traveller get his hands on this stuff?

Well, you can actually just go out and buy special outdoor clothing that has already been pre-treated with permethrin if you don’t want to do the treatment yourself.

This option has the advantage that the treatment will usually remain effective for much longer than the DIY method. For example, some companies claim that their permethrin-treated clothing can endure 70 washes before losing effectiveness.

Clothing and gear that you treat yourself on the other hand will probably need to be re-treated after about 6 washes, and once a month or so even if you don’t wash it at all.

The DIY method however means that you don't have to go out and buy a whole new set of permethrin-infused clothes, and you can just treat your regular travel wardrobe with a spray can.

Procedure for treating clothing with permethrin

If you want to impregnate your clothing and other gear with permethrin in the DIY fashion, the first step is to hang up your clothing and any other gear to be treated on hangers outdoors (never do this indoors), so that you minimize inhalation of the fumes from the spray.

It’s best to use permethrin that is approved for treating clothing, as this is formulated with certain ingredients that help it to adhere to fabrics. You can try Repel Permethrin Aerosol Spray, which is specially designed for treating clothing and gear.

The stuff that’s used as an agricultural insecticide might not stick to the fabric as well and you might also end up with the wrong concentration after diluting it if you don't know what you're doing, so it's better to stick to the dedicated aerosol spray.

Many people make the mistake of spraying everything too lightly – you need to be a bit heavy-handed, spraying the clothing and gear until it turns noticeably darker in colour and is thoroughly dampened (although it shouldn’t be dripping wet).

Once the process is complete, the treated clothing and gear should not be worn or used until it has fully dried.

It’s important to be aware that permethrin-treated clothing and gear alone will not provide adequate protection against mosquitoes and other insect pests.

Remember that permethrin is only applied to clothing, gear and nets, so it won’t protect any exposed skin that you may have on display.

For this reason, you should always use permethrin treatment in conjunction with a topical mosquito repellent that you apply directly. to your skin.

As regards the health implications of exposure to permethrin, it’s generally considered reasonably safe for humans when used in the correct fashion. However, you shouldn’t apply it to your bare skin, as it could cause irritation or even burning.

For fish and cats, permethrin is an entirely different story, as both animals are extremely susceptible to the stuff and can die when exposed to low levels of it, so don’t let it get anywhere near your fish bowl, aquarium and cats.

#7 - Clip-on mosquito repellents

Clip-on mosquito repellents are a type of spatial repellent that are designed to create a zone around your body that mosquitoes are discouraged from entering.

These gadgets are usually comprised of a compact, portable unit that incorporates a miniature fan and a replaceable cartridge that contains the active repellent ingredient, which is often metofluthrin or some other pyrethroid compound.

You can clip these gizmos onto your belt or pocket while you go about your business and the little battery-powered fan will blow and disperse the repellent into the space surrounding your body.

Manufacturers claim that their products can provide 8-12 hours of full-body protection from biting mosquitoes, but many consumers have reported receiving multiple bites while relying on these clip-on devices for protection.

Check out this video, which reports on an informal experiment that was carried out by Consumer Reports to test the efficacy of one of these clip-on repellents.

During the experiment, test subjects were kitted out from head to toe in protective gear (think beekeeper-type suit) and exposed to hundreds of bloodthirsty mosquitoes inside a screened enclosure.

The test subjects were monitored closely to see how many mosquitoes landed on their bodies and they were also asked to expose a portion of bare skin on their arms to see how many bites they received.

The purpose of the experiment was to verify one manufacturer’s claim that its product is effective for 8 hours but unfortunately, the experiment had to be curtailed after just 2 hours due to the test subject’s being repeatedly bitten by the hungry mosquitoes.

Consumer Reports ended up including clip-on repellents in an article entitled "5 Types of Insect Repellent to Skip".

In spite of the alleged outcome of the Consumer Reports experiment, some people do swear by clip-on repellents, so there probably are certain conditions under which they can be effective.

It’s likely that in situations where only a moderate level of protection is required, these gadgets could help to prevent biting. It’s logical that they would be most effective in windless conditions and when the user is remaining stationary.

If using the clip-on repellent while walking for example, the repellent would tend to trail behind you instead of forming a protective barrier around you.

Topical repellents are generally considered to be much more effective for outdoor use, but if you’ve experienced adverse side-effects or have had other issues with topical repellents in the past and you’re looking for alternatives, I would say there is no harm in giving these clip-on repellents a try.

You can check out Off! Clip-On Mosquito Repellent, which comes with included AAA batteries for the fan and one repellent refill. Additional refill packs can be bought separately. Each repellent disc is supposed to provide up to 12 hours of head-to-toe protection.

#6 - Mosquito repellent bracelets

Mosquito repellent bracelets are another kind of spatial repellent that have always been an enticing solution for the irresistibly attractive (to mosquitoes) traveller.

The notion that one can simply slip a stylish-looking bracelet over one’s wrist and suddenly have full immunity in all situations from mosquito bites has undeniable appeal; it recalls the magic talisman or amulet that many people wear for good luck and protection from evil powers.

Made from silicone and often adjustable to fit all sizes of wrists and ankles, mosquito repellent bracelets or wristbands are typically impregnated with natural essential oils like lavender oil or citronella oil, causing them to give off an odour that mosquitoes can’t stand.

If stored after each use in the original sealable pouch they come with, these fragrant bracelets can supposedly remain effective for up to 240 hours. They normally come in a wide selection colours and are even safe for infants to wear.

Some people will swear by the efficacy of mosquito repellent bracelets, whereas most experts will probably tell you that they are a total sham or that they only offer localized protection from bites in the wrist area where they are worn.

I personally would never trust them with my life if I was going into the jungle or trekking in other mosquito-plagued environments. But if your life is not at stake, then sure, there would be absolutely no harm in trying them out to see if they work for you.

A popular choice are the Mosquitno Waterproof Mosquito Repellent Wristbands, which are infused with natural citronella oil and are supposed to provide up to 5 days or 120 hours of protection.

The bands are lightweight, comfortable to wear and come in a range of colours (our favourites are the camo and tie-dye). After use they store in a resealable pouch to preserve their effectiveness.

#7 - Mosquito repellent patches

Mosquito repellent patches are fragrant, adhesive patches or stickers that are designed to be stuck to clothing, tables, bedsides, prams (if you have an infant) and so on, in order to ward off mosquitoes.

They are primarily marketed at children and families, as could be guessed from the cartoonish images that are displayed on the patches of many brands.

Mosquito repellent patches are usually impregnated with one or more 100% natural essential oils and are supposed to act as spatial repellents, creating an invisible mosquito net around you. Some products will claim to offer up to 72 hours of protection.

It's doubtful that these patches have a very strong effect on mosquitoes, but they are probably better than nothing. You can try these DEET-free Repellent Patches/Stickersby Mosquito Guard.

Keep reading to learn about more types of spatial repellents like camphor tablets, mosquito repellent candles and plug-in vaporizers, which we cover in the section below on how to keep mosquitoes away while at your hotel.

When you’re travelling, your accommodation is the one place that needs to be a refuge from mosquitoes and other biting insects.

You should be able to relax completely and not have to worry about contracting dangerous illnesses like malaria, dengue and chikungunya.

Unfortunately however, unless you’re willing to shut yourself inside an airtight, hermetically sealed box with no windows, gaps or air vents, a few mosquitoes will probably find their way into your room if your locality has a reasonably large population of them.

Insect mesh screens installed over the windows in some rooms can definitely help, but still can’t be relied on to keep the bugs out entirely.

Beach huts, stilt houses, humble rural cottages and other types of cheap accommodation can be especially prone to mosquitoes due to the rooms being less well sealed in general.

When mosquitoes do manage to infiltrate your private space, that presents a real problem, as they can seriously disrupt your sleep and your ability to relax, and you can’t simply walk away from the problem like you can often do in the outdoors.

Below we’ve outlined the best solutions for ensuring that the bugs stay out of your hotel room.

#1 - Stay in an eyrie

The word “eyrie” or “aerie” most commonly refers to an eagle’s nest built high in a tree, on a cliff ledge or in some other inaccessible location.

But the term can also refer more generally to any relatively high or inaccessible place from which one can observe everything below them.

In this context, we’re referring to a hotel room that’s situated high up in a tall building. By elevating yourself to lofty heights, you remain far removed from the insect-related problems and concerns that afflict the ground dwellers below.

This works because mosquitoes generally don’t like to stray more than 50-100 metres, either horizontally or vertically, from their breeding grounds.

In the case of really tall buildings there will also be a noticeable drop in air temperature and an increase in wind velocity as you go higher, both of which discourage mosquitoes.

This doesn’t mean that you won’t ever find mosquitoes flying near the tops of tall buildings (you will) but it means that the probability of encountering them decreases as you ascend higher.

How high do you need to go to see a difference? It’s generally recommended that you choose a room on the 4th floor or higher.

Rooms that are really high up are often associated with luxury hotels but occasionally you can snag eyries at budget prices.

In a past trip to Manila, Philippines, we stayed in a Zen Rooms Space Taft budget room on the 27th floor of a skyscraper.

The room had free Wi-Fi, AC, ensuite bathroom, hot water, a fridge, a microwave, a large kitchen sink, free towels and a stunning view of the city below from the window, all for less than $10 a night. Needless to say, we had no problems with mosquitoes in that room.

#2 - Turn up the fan speed

It almost sounds like too simple a measure to be effective, but if you’re staying in a room with a ceiling, pedestal, table or wall-mounted fan, the air current it blows across your body can sometimes be all that’s required to keep hungry mosquitoes at bay.

But what if it’s cold and you don’t want to turn on the fan? Luckily, mosquitoes will mostly only be a nuisance when its warm, which is when you’d be turning on the fan to keep cool anyway.

A fan helps to keep mosquitoes away because:

(a) mosquitoes are unskilled pilots in high winds

(b) a fan helps to disperse the carbon dioxide, body odours and other chemical cues that allow mosquitoes to detect your presence and determine your exact location

While the really desperate or hungry mosquitoes will still try (sometimes successfully) to land on your alluring body in spite of the gale force winds, a fan running on its medium or high speed setting definitely helps to hold them off.

#3 - Turn on the AC

Just like with a fan, the air current generated by an AC unit makes it more difficult for mosquitoes to fly and also helps to disperse the odours that allow mosquitoes to pinpoint your location.

But the primary reason that air-conditioning can be so effective in banishing mosquitoes is because it lowers the room temperature and relative humidity to a level that mosquitoes don’t like. They hence become inactive and stop feeding.

Having the AC turned on will also mean that you cool down, which will cause you to emit less body heat and body odours (by perspiring less), which makes you less “visible” to mosquitoes.

Another thing to consider is that rooms that have AC installed tend to be more airtight, since the owner of the property will want to minimize his electricity bill. A more airtight room means fewer ways for mosquitoes to enter in the first place.

#4 - Exterminate the existing intruders, then prevent any new ones from re-entering

Want to completely purge your room of mosquitoes and then make sure that no new ones enter?

Mosquitoes aren’t that difficult to dispatch, especially if there are only a few of them lurking inside the room.

One tactic that can work well is to lie motionless on the bed for a few minutes with the fan turned off, waiting patiently for any mosquitoes to land on you.

Then when a mosquito makes contact with your skin, decides the coast is clear and begins to feed on your blood, you can then suddenly, with a lightning-fast motion of the hand, splat it against your body.

Mosquitoes are also easy to spot and splat when they’re perched motionless on the wall (although this does often leave behind a bloody mess), especially if the wall is painted a light colour like white or cream.

For airborne mosquitoes, you can crush them or capture them by making a tight fist around them with a rapid thrust of the hand.

Another popular means of dealing death is to clap both your hands together at just the right moment so that the airborne mosquito gets mashed in between them.

If for some reason the act of killing mosquitoes makes you feel guilty, you can also try to trap the mosquito in a glass or mug when it's sitting on a wall, table or other surface. You can then slide a piece of card or paper under the mug and transfer the mosquito to the outdoors.

Mosquitoes often like to skulk among potted plants, curtains, towels, hanging clothes and in other shady areas so make sure you inspect all these potential hiding places before concluding that you’ve eradicated them all.

Once you think you’ve exterminated all the mosquitoes in the room, you should then try to block off any gaps and openings from where they could potentially re-enter.

Close any open windows (you can leave them open if they have hole-free insect mesh screens), maybe try stuffing a towel underneath the door and try to block up any other obvious gaps that you can see.

Unfortunately, some rooms will have large ventilation openings (which may be fitted with metal security bars) at the top of the walls and these can be difficult to block up. If you ever find yourself in that situation, you should look at some of the other solutions.

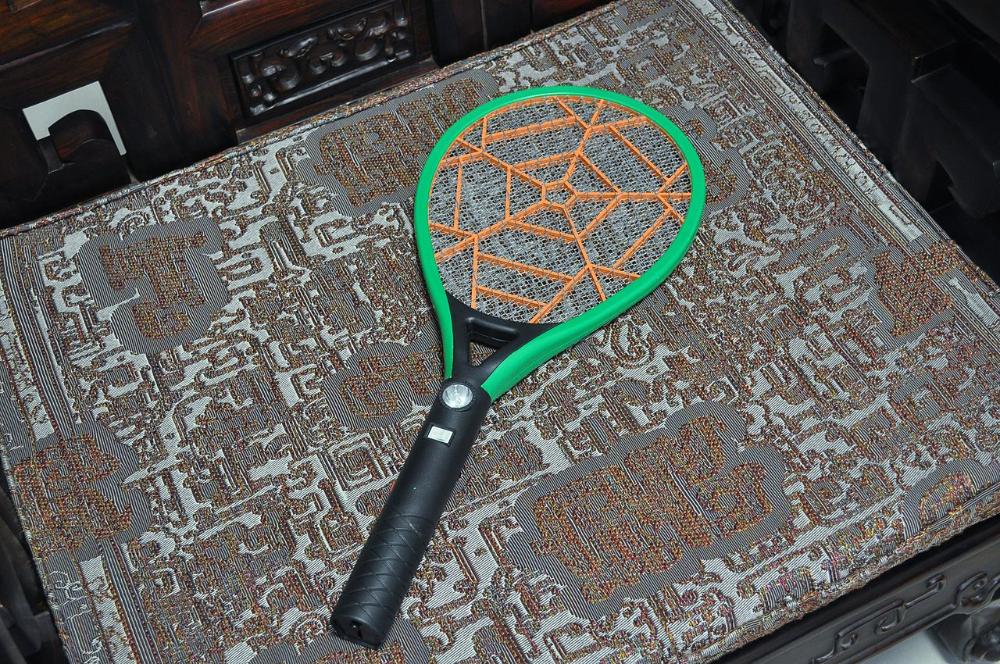

#5 - Use an electric fly swatter to zap the mosquitoes

Electric fly swatters, also known as mosquito bats or racket zappers, are way too big and heavy to carry with you when travelling, but the owner of your hotel or guest house might let you borrow one to zap all the mosquitoes in your room.

These tennis-racquet-resembling contraptions run on rechargeable or disposable batteries and can generate very high voltages (usually 500 – 2,750 V) when a button on the handle is pressed.

Any mosquitoes (or other flying insects) that are unfortunate enough to fly into the metal grid of the racquet will die a spectacular death by electrocution, generating sparks, smoke and sounds like those of firecrackers going off in the process.

Many electric fly swatters possess a three-layer grid, which is comprised of an inner wire mesh layer sandwiched between two outer layers of parallel metal rods.

The inner mesh layer and outer rods are oppositely charged, so that when a mosquito touches against both simultaneously, a short circuit develops and a spark passes through the insect, stunning or killing it on the spot.

Another electric fly swatter design uses just a single-layer of parallel rods, with adjacent rods carrying opposite charges.

Regardless of the method of electrocution used, these contraptions are very effective at killing mosquitoes and other flies because their relatively open grid means that insects aren’t forewarned of their imminent death by a whoosh of air, as with traditional fly swatters.

Their other advantage is that they don’t require mosquitoes to be crushed against a wall, table or other flat surface, which usually leaves a terrible mess, especially when the mosquito is already filled with blood from a previous feeding session.

#6 - Camphor tablets

Chemical formula: C10H17O

Camphor is an age-old, natural mosquito repellent that people have used for generations to keep their living spaces mosquito free.

This white, volatile, aromatic, waxy, crystalline substance (a terpenoid ketone) used to be primarily made by distilling the bark and wood of the camphor laurel tree (Cinnamomum camphora), a native of China, Japan, Taiwan and other east Asian countries. Nowadays however, camphor is mostly synthesized from turpentine.

Camphor was used to make mothballs in the past, though these days mothballs are normally made from either naphthalene (a white solid derived from coal tar) or pdichlorobenzene.

The latter is probably best known for its use in those deodorizer cakes found in men’s urinals and it represents less of a fire hazard than naphthalene.

Camphor has also been used in toolboxes as the vapour it emits inhibits rust and you will find it as an ingredient in some cough medicines and in Vicks Inhaler nasal sticks too, as it works as a cough suppressant and decongestant. It also has anti-bacterial, anti-fungal and anti-inflammatory properties.

When you’re travelling you may come across shops that sell packets of small white camphor tablets or cubes.

If you want to expel mosquitoes from your room in a hurry, you can place one of these camphor pieces in a metal bowl or other non-flammable container and set it alight with a match or lighter.

Camphor tablets are highly combustible and when burned will fill the room with an acrid smoke that will drive any mosquitoes out, although there is always the risk when doing this that the fumes might drive you out of the room too.

A more gentle, slow-release approach is to just leave a few camphor tablets in the corners of the room and take advantage of the fact that camphor sublimes (turns directly from a solid into a gas without becoming a liquid) at room temperature. Within the day or so the tablets will have vanished.

Another common method is to place a few camphor tablets in a shallow ceramic or metal bowl that is suspended over a burning tealight.

The heat from the burning candle helps to vaporize the camphor more quickly, thus helping to ward off stubborn mosquitoes. The tablets could also be placed on other warm surfaces to achieve a similar effect.

Although camphor is highly toxic when ingested (just 5 g can be lethal to an adult human), the relatively modest amounts of vapour released into the room when using the gentler methods described above shouldn’t do you any harm when inhaled.

#7 - Mosquito repellent candles

Many people pack a small candle or a few tea lights when they travel to serve a variety of purposes including:

- Emergency lighting backup during unexpected power outages

- Relaxation or meditation at the end of a tiring day of sightseeing

- To create a romantic or homely ambience in the bedroom or bathroom

- To deodorize a fetid bedroom or bathroom

- To help create a bug and mosquito free environment.

For the lattermost purpose, ordinary candles won’t cut it - you’ll get far better results by burning a specially made mosquito repellent candle.

Mosquito repellent candles can vary in size from small tealights to much bigger candles and most are infused with or more plant-derived essential oils such as rosemary, peppermint, mint, tea tree, citronella, cedarwood, lemongrass and so on.

Most of these candles will produce a very pleasant aroma when burned due to the natural oils they contain.

It’s important to understand that mosquito repellent candles are not very potent deterrents and should not be relied on in travel situations where you might be liable to experience a severe mosquito onslaught.

Nevertheless, they can make a lot of sense when you’re planning to bring candles on a trip anyway, or if you aren’t expecting to have too much trouble with mosquitoes.

One of the upsides of mosquito repellent candles is that the vapours they give off are safer to breathe in than those of synthetic chemical repellents. The only significant risk with using these candles seems to be that certain people can be allergic to citronella.

I feel that the tealight-sized mosquito repellent candles are the most suitable for travel due to their compactness and portability.

Having a dozen or so tealight candles also allows you to light a ring of them around you so that you are encapsulated inside an invisible mosquito net. Tealights are usually designed to burn for 2-3 hours, which should be long enough to drive out the bugs.

You can try these fragrant Mosquito Repellent Tea Lights by Mosquito Guard, which come in a 16-pack. They're made with all-natural essential oils like citronella, peppermint, lemongrass, rosemary and cedarwood.

#8 - Use a mosquito net over your bed

Mosquito bed nets come in a variety of colours, sizes and shapes, including cones, pyramids, cylinders, domes and most commonly, boxes.

Whatever the design though, all serve the same purpose - to create a bug-free zone over your bed so that you can sleep without being tormented by mosquitoes.

As long as you remain inside this tranquil haven, mosquitoes can only buzz around outside the net in futility, being too big to pass through the fine mesh of the net to reach you. You'll still often hear the annoying high-pitched whine, but at least they won't be able to get you.

The only two caveats for the net to work properly are that the mosquito net shouldn't have any holes in it and your body shouldn't make contact with any part of the net while you sleep, as mosquitoes can then bite you through the net.

If everything is set up correctly, the mosquito bed net is an effective way to achieve a night of restful sleep in a room that’s teeming with famished mosquitoes.

The advantage of a bed net over some other methods (see below) is that you’re not inhaling smoke from incense or mosquito coils, nor are you breathing in potentially harmful chemical vapours from plug-in repellents.

However, bed nets also have a few drawbacks and some people don’t like sleeping under them for those reasons.

Firstly, they won't always be set up when you need them to be and the task of setting them up can be a bit of a pain if you're not familiar with the net design and the procedure. You might need to seek some assistance from a member of staff or the owner of your accommodation.

Secondly, bed nets make it a little inconvenient to get in and out of the bed during the night, like when you get up to go to the bathroom.

Each time you want to get out of bed the net will need to be untucked from underneath the mattress to allow you to exit, and will need to be re-tucked when you get back into bed.

Bed nets can also engender a sense of confinement, making you feel as if you’ve walled yourself inside a prison in order to keep the mosquitoes out.

If it's a warm night and you’re relying on a fan to stay cool, another issue with bed nets is that they can significantly hamper the airflow reaching you from the fan.

Sometimes you can compensate for this effect by just maxing out the fan speed, but what about those really warm nights when you need the full, unimpeded flow of air from the fan on the highest speed setting just to stay cool?

Another problem that can crop up, as we already alluded to, is that the mosquito box nets that you are provided with may be pockmarked with hole and tears (some of which may have been made by the red hot ends of cigarettes and joints that were carelessly smoked too close to the net by previous guests).

We have managed to patch up small holes in mosquito box nets in the past using electrical tape, which is why we usually carry a small roll with us whenever we’re on the road.

So, should you carry a mosquito bed net with you when travelling to countries where mosquitoes are rife?

Actually, I wouldn’t recommend carrying one for a couple of reasons.

The first reason is that in some rooms you may not be able to find viable attachment points that would allow you to suspend the net over the bed. In that very common situation your net becomes redundant.

The second reason is that in accommodation where mosquitoes are a major problem, the management will most likely be able to provide you with a bed net or will have some other solution for dealing with the mosquitoes.

#9 - Plug-in vaporizer mosquito repellents

Another solution for combatting mosquitoes in your room is an electrical device known as a plug-in vaporizer, which diffuses chemical vapours that are hazardous to mosquitoes (and relatively harmless to humans) throughout the room.

Plug-in vaporizers fall under the category of spatial repellents, as opposed to topical repellents that you would apply directly to your skin.

(There is another plug-in device that uses ultrasonic waves to ward off mosquitoes, but we are not recommending these here, as they have been largely dismissed as being ineffective by the scientific community.

If you're still interested you can check out the Neatmaster Ultrasonic Pest Repeller, which claims to be effective against a whole host of pests including bed bugs, mosquitoes, spiders, ants, flies, cockroaches, fleas, mice and more. The device lets you choose between three different modes, depending on the severity of the infestation. Surprisingly, the product has a lot of glowing reviews on Amazon.)

I am not sure if plug-in repellents are used in all the world’s mosquito-plagued countries, but I do know that in India they are quite commonly used in households, with Good Knight, All Out and Mortein being among the best-known brands there.

The “Good Knight” brand of plug-in vaporizer that I’m familiar with resembles a bulky adapter. It consists of an electric heating element enclosed within a hard plastic casing. Into the unit screws a small, replaceable, 45 ml PET bottle that is filled with a colourless, volatile liquid mixture.

Assuming typical daily use (7-8 hours), a single one of these replaceable bottles will usually last for about 3 weeks and, in India at least, they cost about €1 or Rs. 80/- each to replace. That works out at about €0.04 for a full night of mosquito protection.

The active ingredient in the liquid mixture is usually some kind of pyrethroid insecticide like allethrin, prallethrin, transfluthrin etc. at a low concentration of 1.6% w/w.

As we mentioned previously, pyrethroids are synthetic compounds that mimic pyrethrum, a natural insecticide found in Chrysanthemum flowers.

They are a popular choice in mosquito repellents because at low concentrations they are highly toxic to insects but relatively harmless to mammals (including us humans).

The other crucial component in this technology is the porous clay carbon wicking rod that passes through a hole in the top of the bottle so that the bottom of the rod is immersed in the liquid and the top sticks out of the bottle.

When the device is plugged into a working power outlet, a small indicator light will come on to indicate that it’s now active. A switch on the unit allows you to toggle between “Activ+” and “Normal” modes, depending on how pesky the mosquitoes are.

When switched on, the liquid inside the bottle is continuously being wicked up to the exposed top part of the clay carbon rod via capillary action, where it gets vaporized by the heat from the electrical heater.

The vapours immediately begin to diffuse through the room and start to work their intoxicating magic on the mosquitoes. After about 9 minutes it should supposedly start having an effect, but in my experience it can sometimes take a bit longer than that for the biting to abate.

The active ingredient in the vapour disrupts the nervous system of the mosquitoes, causing them to lose control of their bodily movements (ataxia). They soon become flightless (an effect known as KD or knock-down) and paralyzed.

Any mosquitoes outside the room are also deterred from entering while the vaporizer is plugged in, as they essentially see it as a hostile environment.

One of the primary advantages of plug-in vaporizers is their ease of use. The only preparation required is to ensure that all windows and doors are closed and then it’s really just a matter of plug and play.

As long as you don’t have any protracted power outages during the night, any mosquitoes that were in the room should remain knocked out until the morning.

Keeping a fan running in the room while the vaporizer is switched on is not a problem and will help to disperse the active ingredient throughout the space more rapidly.

Plug-in vaporizers are preferable to mosquito coils (see below), which can require fiddling around with matches for several minutes to get them lit, can require relighting during the night and which fill the room with noxious smoke, which is definitely not good to be breathing in!

It’s worth noting however that not all mosquitoes are equally affected by pyrethroid vapours, with differences observed between species and also individuals. Some strains have even become resistant to certain pyrethroids.

Bear in mind also that these plug-in vaporizers are designed to be used in smaller rooms and will become less effective in very commodious rooms, as the poisonous vapours will become too dispersed.

In general though, these plug-in vaporizer repellents are effective and they get the job done.

As regards safety for humans, although many people can leave a vaporizer plugged in all night without suffering any ill effects, some people do report headaches and people with asthma can be particularly sensitive.

Cats are also particularly vulnerable to pyrethroids (due to an inability to metabolize them efficiently), so if you travel with a pet cat, this is not the right mosquito-repellent solution for you.

To minimize your exposure to the vapour, it’s recommended that vaporizers be plugged into the power outlet that’s furthest away from where you’re sitting or sleeping in the room.

So, should you carry a plug-in vaporizer with you on the road?

Plug-in vaporizers are lightweight and fairly compact, and you can’t always count on your hotel or guesthouse to be able to provide one, which is why some people carry one at all times during their travels.

If you’re on the move with a vaporizer, always remember to unscrew the bottle from the main unit and replace the original screw cap that came with the bottle to prevent spillage of any liquid.

Some people have suggested that both the liquid bottles and the electrical units should be placed in checked luggage, as some travellers trying to bring them in hand luggage have had them confiscated by airport security.

Also, it's worth noting that good quality heaters are usually serviceable for 3-4 years before needing replacement, whereas it’s recommended that you replace lower quality heaters every year.

In countries where the replaceable liquid bottles can be bought, you’ll normally find them for sale in convenience stores, mini-marts, general stores and the like.

#10 - Mosquito coils

Mosquito coils are spiral-shaped strips of self-combusting material that slowly burn like a fuse once lit, releasing a steady stream of smoke and mosquito-repelling vapour into the air.

Coils are widely used for mosquito protection throughout Asia, Africa and South America, but Europeans and North Americans will be less familiar with them, as they never became fashionable on these two continents for some reason.

The mosquito coil was invented in the late 1800s by a Japanese mandarin exporter named Eiichiro Ueyama, who was trying to create insect-repelling incense sticks from a starch base mixed with dried, powdered Chrysanthemum flowers, which contain the natural insecticide pyrethrum.

Ueyam's wife suggested that he could make the sticks burn for longer by making them longer and coiling them into a spiral, thus giving birth to the first mosquito coil. The coils proved to be a hit and were hand-rolled until the process was mechanized in 1957.

Nowadays mosquito coils come in a variety of different colours and sizes, and are designed for both indoor and outdoor use.

The active ingredient in the coils of today is usually some kind of pyrethroid (synthetic insecticide) like prallethrin, d-trans allethrin, or some type of natural essential oil.

The combustible base material is normally made from biomass and is infused with a very small amount of the active ingredient (typically 0.04% - 0.1% w/w).

Mosquito coils usually come with a small upright metal stand, which has a sharp point that can be pushed into the centre of the coil so that it is supported a few inches above the ground and doesn’t leave scorch marks on the floor as it burns.

Once lit a typical mosquito coil will burn continuously for around 6-8 hours, although I have also come across larger coils that will burn for 12 hours.

Occasionally, burning coils can get extinguished for no apparent reason and have to be relit again. If there is a lot of air circulation from say, a breeze or a fan, coils will burn faster and won’t last as long, although they are less likely to go out prematurely.

Mosquito coils are usually comparable in cost or even slightly cheaper than plug-in repellents. In India for example, a box of 10 standard size coils costs just Rs. 26/-, which works out at about €0.03 per coil providing 6-8 hours of protection.

Coils (and bed nets) are commonly used in low-income households in tropical and sub-tropical countries, since they are cost-effective and also not reliant on electricity like the plug-in repellents.

Personally, I’m not a big fan of burning mosquito coils in confined, indoor spaces because the smoke from them irritates my eyes, causing a burning sensation accompanied by profuse waterworks.

For some people, the smoke can also irritate the lungs and throat. It’s plausible that long-term exposure to the particulate matter from burning mosquito coils could lead to lung problems, though infrequent use is probably not too hazardous.

It is possible to reduce the amount of smoke you’re exposed to when burning mosquito coils by placing the burning coil further away from where you’re sitting or sleeping, by keeping windows and doors open and also by only burning coils in large, airy rooms.

Another option to reduce inhalation of smoke is to “fumigate” the room by vacating it for a few minutes while the burning coil fills the room with smoke and drives out all the mosquitoes and other bugs.

You can then extinguish the coil and wait for the smoke to be mostly cleared before returning to the room and then blocking off any gaps that mosquitoes might re-enter from.

If you're travelling to a place where you might not be able to buy mosquito coils locally, you can also buy them online before your trip. Try these S C Johnson Off! Mosquito Coils, which come in packs of 6 and burn for 4 hours each with a country fresh scent.

#11 - Incense

When you hear the word “incense”, it probably conjures up images of combustible cones or coated sticks that are burned to suffuse a room with a pleasant fragrance or to help with meditation or relaxation.

Incense has been used in various parts of the world since antiquity as an aid in ritual, meditation and healing. It has also been used as a simple air freshener and as an insectifuge (insect repellent), which is the use we’re most interested in here.

When incense is burned it produces a continuous stream of smoke that slowly diffuses through the surroundings, thus helping to drive away mosquitoes and other insects.

Regular incense sticks usually burn for 20-30 minutes, while other forms of incense can burn for much longer.

Today much of the world’s incense is produced in India, where around 200,000 local women work part-time in hand-rolling raw, unscented incense sticks at home.

The incense sticks are produced by adding water to a blend of dry, powdered ingredients to form a moldable paste or dough, which is rolled onto a thin stick and then left to dry over a period of several days to form the semi-finished product.

The rolled sticks are then passed on to any of the country’s (roughly) 5,000 incense companies, which apply their own unique brand of perfume and then package the incense sticks for sale.

The price per stick can vary depending the brand and ingredients used, but I’ve seen boxes of 90 incense sticks sell for just 29 rupees in India, which pegs the price per stick at less than half a (US) cents, making incense a pretty cost-effective mosquito repellent.

But is incense actually an effective mosquito repellent? Will it keep mosquitoes out of your room? It’s probably true that burning incense is in most cases not as effective as burning say, a mosquito coil.

Regular incense sticks produce a smaller quantity of smoke than a coil and their primary function is to fill the room with a pleasant fragrance, not to fill it with smoke and drive out mosquitoes. Incense cones however produce a greater quantity of smoke than the sticks and should be more effective.

I would say that if you’re staying in a relatively small room and mosquitoes are not bothering you that much, burning two or three incense sticks might be all that’s needed to keep them at bay.

I often burn incense myself when I’m getting the occasional mosquito bite and I do find that it makes a difference.

When you’re travelling and mosquitoes strike, we recommend buying a pack of the self-combusting, masala-style Indian incense sticks, which are known in India as agarbatti. Once ignited, you can just leave them alone to slowly fill the room with their smoke and fragrance.

There are other kinds of incense that are not self-combusting and instead require an external heat source such as a burning piece of charcoal or an electric incense heater, but when travelling it’s best to stick with the self-combusting forms, since these are the simplest.

Because incense-making is a highly unregulated industry, we also advise that you try to stick to natural incense made from all-natural powdered ingredients like roots, stems, leaves, flowers, fruits, wood, gums, resins, essential oils and so on.

Some of the common natural ingredients used in making incense include sandalwood, cedar wood, star anise, patchouli, turmeric, clove and ginger.

The type of incense to avoid is synthetic incense (also known as dipped incense), which is made by dipping blanks, which have been shaped into sticks or cones, into fragrant synthetic oils to scent them.

The problem is that many of these fragrant oils, while perfectly safe when used as intended, are not meant to be burned, and doing so may release harmful fumes into the air.

Some manufacturers will also add extenders like dipropylene glycol (DPG) to these fragrant oils in order to dilute them and increase profits. The problem with DPG is that it releases poisonous gas into the air when burned!

Even the blanks that are used in synthetic incense can be problematic, as they are sometimes made with sawdust from plywood, which contains toxic glues that can release formaldehyde when burned.

With synthetic incense, there’s just no way to know what you’re really burning, which is why it’s best avoided.

The word “mosquito” actually derives from the Spanish mosca (fly) and the suffix ito (small), so it literally means “little fly”.

Mosquitoes are small, flying, six-legged insects belonging to the family Culicidae, which is within the order Diptera (the true, two-winged flies).

They have a pair of compound eyes, a pair of antennae (which are noticeably bushier in males compared to females), a pair of wings, a slender segmented body, three pairs of legs and very sophisticated mouthparts for siphoning blood from their victims.

Some interesting facts about mosquitoes are that they can beat their wings between 450 and 600 times per second and their abdomens can hold three times their own weight in blood.

Mosquitoes have existed in one form or another for at least 90 million years, as is evidenced by the find of a partially preserved adult female mosquito (Burmaculex antiquus) in Burmese amber that has been dated at 90-100 million years old. The mosquito belongs to Chaoboridae or the Jurassic fossils, a sister group of Culicidae.

A one-of-a-kind rock fossil of a 46-million year old, blood-engorged mosquito was even discovered by amateur fossil hunters in Montana over three decades ago.

There are 112 genera and over 3,500 species of mosquitoes in the world at present and the bloodsucking nuisances are found on every major landmass except for Antarctica.

With that said, there is one island that is believed to be completely mosquito-free and that is Iceland.

The absence of mosquitoes in Iceland is an intriguing mystery and it’s still not clearly understood why this small European island amid the North Atlantic doesn’t support them.

Temperatures in Iceland are high enough for mosquitoes to thrive (as they do in Iceland’s neighbours like Norway, Greenland and Scotland) and there are plenty of ponds and lakes for them to happily breed.

Exceptions aside though, in most parts of the world mosquitoes are an ever-present menace that most of us have had to learn how to live with.

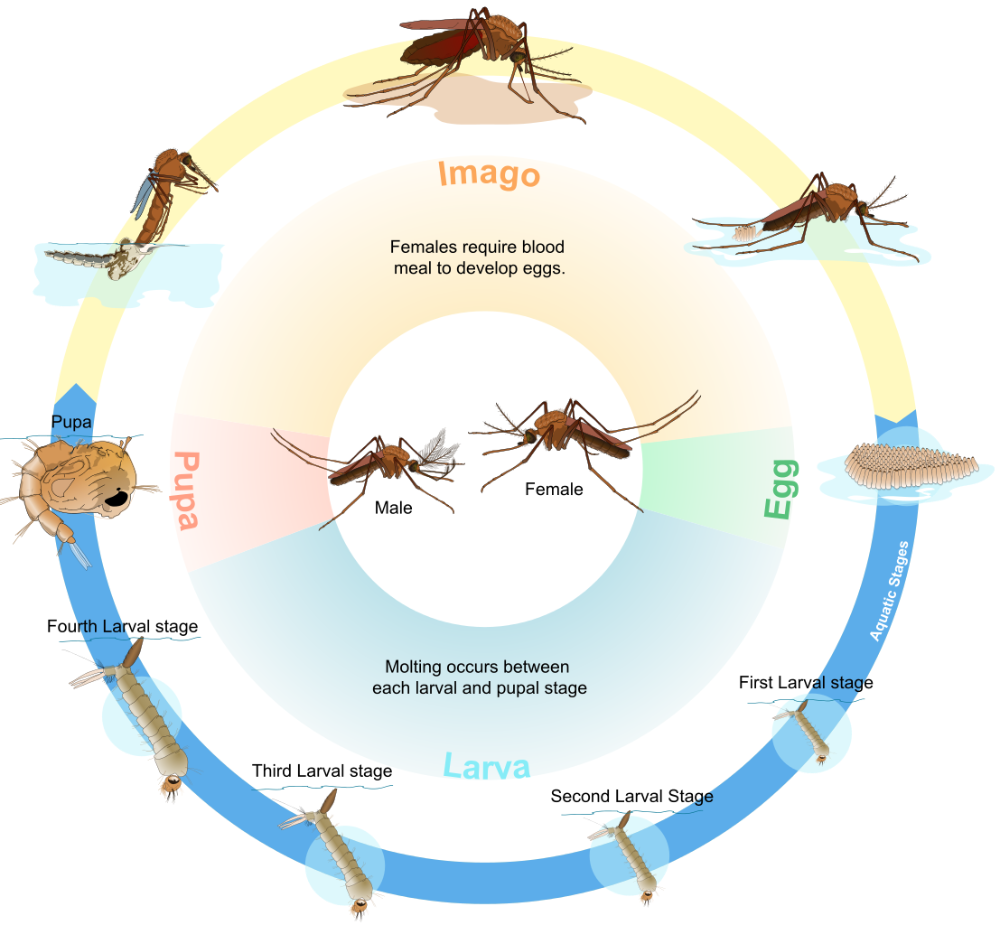

Mosquitoes have a four-stage life cycle, changing from egg to larva to pupa to adult (imago).

The cycle begins when a female adult mosquito lays a clutch of 100-200 eggs after mating and feeding on animal blood.

Depending on the species, the eggs might be laid directly on the water surface, in damp mud near the waterline or may be attached to the underside of water lily pads. Some species deliberately lay their eggs on the water surface in cohesive floating layers called rafts.

Note that mosquitoes don’t require a large water body like a pond or lake to deposit their eggs; even a miniscule puddle of water will suffice for many species. Some types of mosquito will lay their eggs in pitcher plants, hollowed out trees or cupped leaves that hold water.

In man-made environments, mosquitoes will lay their eggs where water has collected or where water might soon collect in a flower pot, old tyre, bird bath, blocked gutter, wheelbarrow, water butt, garbage can, children’s toy, pet water bowl hollow tree stump in the garden etc.

If the eggs survive desiccation, they will usually hatch within 1-3 days after being covered with water, although it could potentially take months for this to happen if the eggs are laid during the dry season or during a cold winter.

When the eggs hatch, the mosquito larvae emerge. They are capable of swimming and are often called “wigglers” or “wrigglers” due to the way that they move in the water.

The larvae develop by feeding at the water surface on algae, microbes and other organic material that they ingest via their mouth brushes.

Over a period of 7-10 days, each larva progresses through four stages of development known as instars, molting at the end of each stage, before it metamorphoses into a pupa.

The pupa is normally comma-shaped and it doesn’t feed but rather spends most of its time near the water surface so that it can breathe through its respiratory trumpets.

If the pupa senses danger, it can swim downwards to escape from the threat. The pupa is often called a “tumbler” because of the way it swims by flipping its abdomen. The pupa develops for 1-3 days until its casing splits and the adult mosquito emerges.