Everything You Need To Know About Visas For Travelling (Full FAQ + iVisa review)

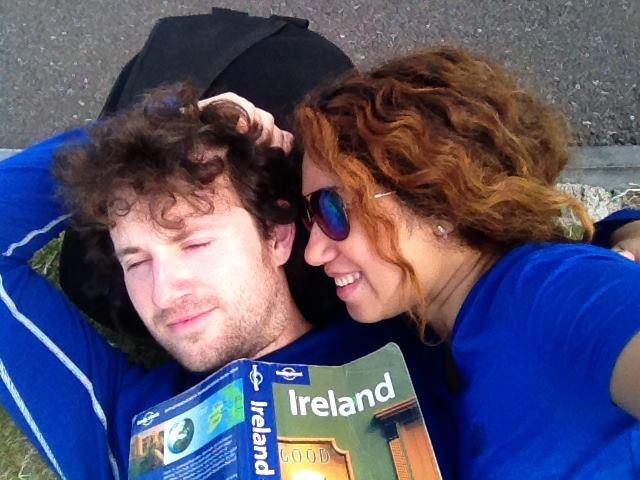

Visas, like travel insurance and data backups, have to rank high among of the least exciting aspects of travel.

We travel to have thrilling new experiences, like trekking amid snow-capped peaks of the Himalayas, watching the sunrise from the top of an active Indonesian volcano, orcavorting through magical hidden valleys filled with rare wildflowers.

Not so we can spend hours trying to decipher inscrutable visa application forms and queuing outside offices at embassies & consulates.

Visas are not only tedious; they can be a downright headache to deal with, a source of stress and confusion, and in most cases are the only major obstacle that stands in the way of you and your dream destination.

But although nobody enjoys having to apply for visas, they're a necessary evil for traveling in today's world. To be able to do the things you love in life, sometimes you have to do certain things that you hate.

Whether you're a long-term nomad that lives on the road, a tourist who travels for pleasure, or something in between, you're going to be dealing with visas a lot if you want to explore this beautiful planet, so it's important to know the nuts and bolts of how they work.

In this comprehensive 16,000+ word FAQ guide to visas, we’ll be covering everything you could possibly want to know about visas.

We'll begin by covering the basics; what visas are, why they exist, who needs a visa and the visa categories that are useful to travellers. We'll then move on to cover the more technical aspects of how visas work, before closing with how to apply for a visa and ensure

Table of Contents

- What is a visa?

- Why do visas even have to exist?

- A brief history of the passport.

- Is a visa also required to exit a country?

- What types of visas are useful to tourists and travellers?

- What is eTA (electronic travel authorization) Is that another type of visa?

- How and where are visas issued?

- For which countries do I require a visa to visit as a tourist?

- Are there any countries that won't issue me a visa?

- Can I exit and re-enter a country without having to obtain a new visa?

- What is meant exactly by the "validity period" and "expiry date" of a visa?

- Can a visa be extended beyond its original expiry date?

- If I'm granted "X" number of days to stay in a country, from which point does the clock start ticking?

- What happens if I overstay a visa?

- What are border runs and visa runs?

- What if my visa application gets rejected?

- If I possess a valid visa, could I still be denied entry to a country?

- How do I apply for a visa?

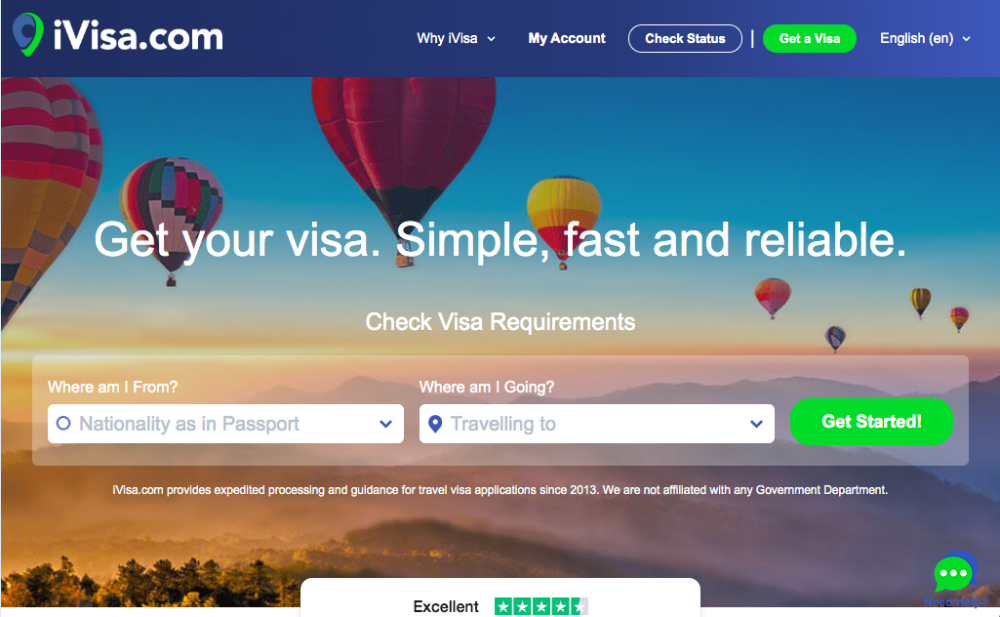

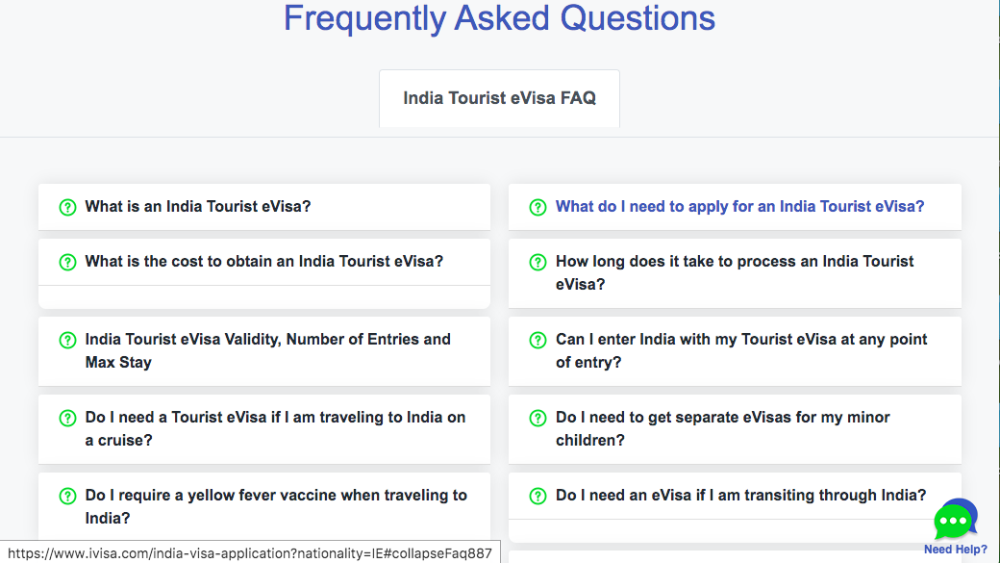

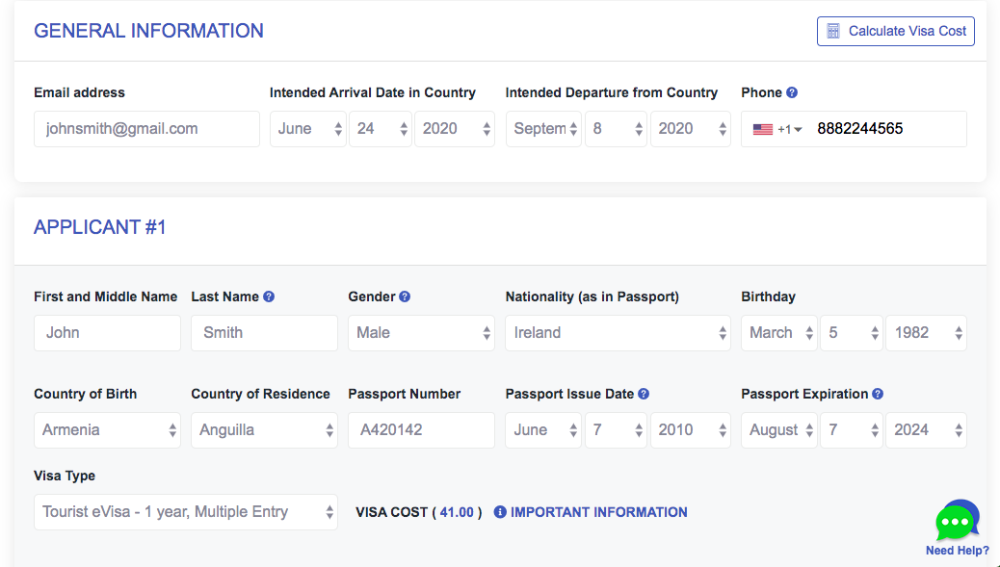

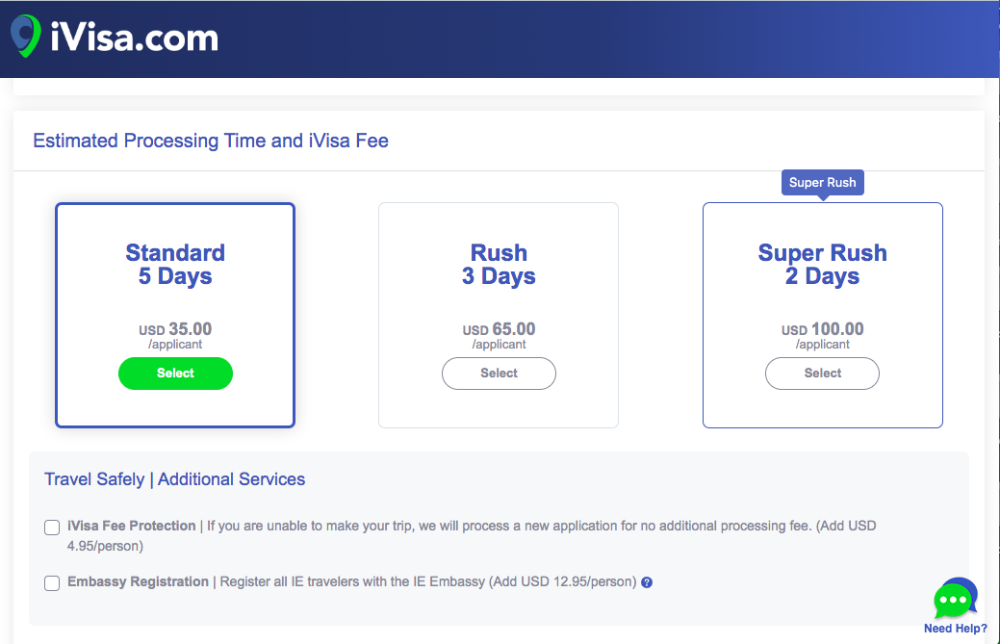

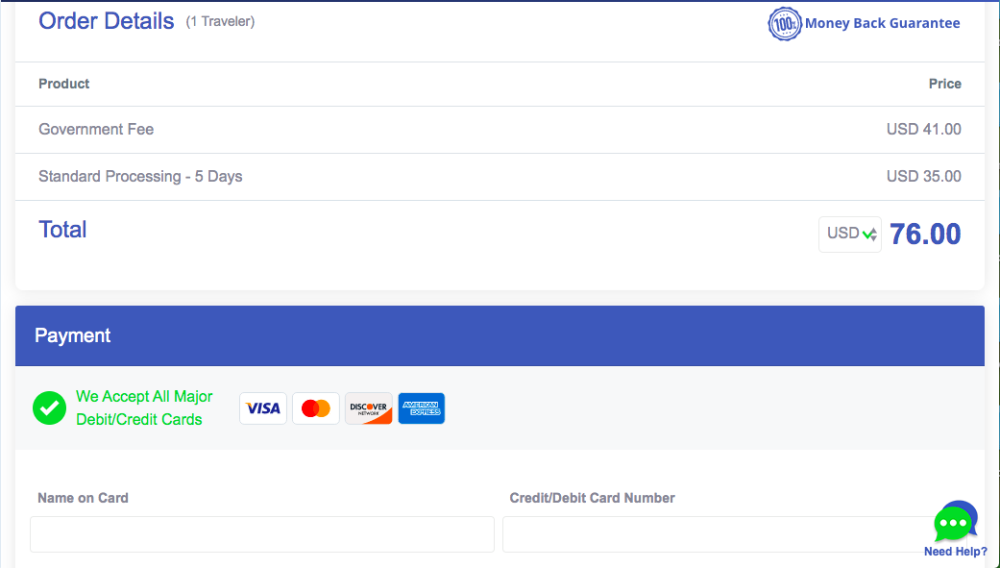

- How iVisa can help you get your visa

- Conclusion

.jpg)

The word “visa” derives from the latin charta visa, meaning “paper that has been seen.”

A visa is typically a sticker or stamp in your passport (also a record in a computer) that informs the gatekeeper of a foreign country that your documents have already been inspected and that you’ve been authorizedby the relevant Government department to enter the country for a specified period and purpose.

Possessing a visa does not guarantee entry to a foreign territory, as the final decision to admit or refuse entry to a visa-holder lies with the immigration officer at passport control, whether at an airport, seaport or land border checkpoint.

Nevertheless, being in possession of a valid visa means that you have an exceedingly high chance of being let in to a country, while trying to enter with no visa at all is a surefire recipe for being rebuffed (unless you’re visiting a country that your nationality has visa-free access to) at the immigration desk.

Whether or not you'll require a visa to travel to a foreign country will depend on a slew of different factors, including the country you're visiting, your nationality, your intended port of entry and the purpose and duration of your visit.

The visas we're familiar with in passports today have been devised by authorities for the following three main reasons:

1) So that authorities can make fully informed decisions regarding whom to admit or deny entry.

An uninformed, snap decision to admit entry to a foreigner who shows up at immigration without prior warning could be disastrous if that foreigner was a terrorist or serial killer.

The visa application process allows authorities ample time to thoroughly evaluate every foreigner who wants to set foot in their country beforehand, so that more of the right people get in and more of the wrong people stay out.

2) So that authorities can impose limits and controls on foreign visitors who are permitted to enter.

Visas permit entry, but also impose boundaries and limits on foreign visitors. They specify how long a foreign can stay in a country for, what activities he can partake in, where he can go within the country and so on.

3) To generate revenue.

The visa system undoubtedly generates a lot of revenue for Governments and is often profitable. Some visas appear to exist more for the sake of generating revenue than for any other reason. This is probably true for any visa that involves a lax application process, where no more information is required from you beyond what's found in your passport.

Other visas however, might require you to undergo an inquisition of sorts, where you have to answer 101 questions of a deeply personal nature and submit a skyscraper-high pile of supporting documents.

When issuing such visas the authorities definitely do care about who you are and what you intend to do in their country.

To understand how the visa and passport situation we see in the world today came about, it may be illuminating to briefly review the history of the passport.

They weren't always called passports, but the concept has probably existed in some form or another for as long as lords, kings and emperors have held sway over people and land.

The first passports were not, like the passports of today, identifying documents that determined which foreign territories an individual could or couldn't enter, and with how much ease or difficulty.

In pre-medieval times of serfdom, landlords and rulers usually (except during wartime) allocated most of their resources towards preventing their own serfs and subjects from fleeing from the farm or workplace, so they probably lacked the power to control who was entering their domain from outside.

In any case, they wouldn't have been too concerned about influxes of migrants, since the situation was the same everywhere; serfs in neighbouring lands would have also been confined to their respective pens by their own overlords, so movement was highly restricted.

And besides, newcomers were treated as assets rather than liabilities in those days, since rulers didn't feel responsible for their welfare and they could be taxed and used as soldiers in local armies.

For all of these reasons, efforts of sovereigns were mostly focused on regulating the internal movements of their own citizens, and a document that regulated the movements of outsiders would have made little sense.

Additionally, the current post-colonial paradigm of a world that's comprised of nation states with clearly defined territorial borders, where an individual's identity is defined by the nation state to which he or she belongs, didn't even exist back then.

A document that determined an individual's degree of mobility according to their nationality would have been meaningless in the distant past, in a world where the very concept of nationality was non-existent or politically meaningless.

So what did the first passports look like and what was their function?

Well, the earliest passports were simply letters of safe conduct or sauf conduit issued by sovereigns, either to their own subjects or to the subjects of another ruler.

These letters mainly served to ensure the protection and safe passage of the bearer while travelling outside of their motherland.

It's interesting to note that passports still serve the purpose of safe conduct today; on the inside cover of the modern UK passport it reads:

"Her Britannic Majesty's Secretary of State Requests and requires in the Name of Her Majesty all those whom it may concern to allow the bearer to pass freely without let or hindrance, and to afford the bearer such protection and assistance as may be necessary."

The earliest known mention of one of these letters of safe conduct comes from verse 2:7 in the book of Nehemiah (the last book in the old testament), where the prophet Nehemiah, who is the cup-bearer of King Artaxerxes I of Persia, is granted letters from the king instructing the governors of the province beyond the Euphrates River to ensure his safe passage through their territories on his way to Judah.

The earliest surviving reference in Britain to one of these safe conduct letters appeared in a 1414 Act of Parliament during the reign of King Henry V.

The act made it high treason for anyone to harm, kill or rob the bearer of the letter, which was a folded piece of paper with writing in Latin and English.

The king could issue these letters to both foreign nationals and to his own English subjects, so that both parties could be assured of their safety when conducting trade outside their respective homelands.

In the early middle ages letters of conduct were issued by Muslim rulers to Christian pilgrims so that they could safely traverse the Islamic-controlled lands to reach Jerusalem.

In more recent times, passes of safe conduct have been issued by governments to an alien or enemy, often to encourage defection.

American forces air-dropped more than 50 billion propaganda leaflets over Vietnam during the war, many of which were safe conduct passes designed to encourage defection of the enemy forces.

In 1917, Germany, who was at war with Russia at the time, granted Lenin and his fellow exiles safe passage through Germany en route from Switzerland to Sweden, in a sealed railway car.

Some letters in times past were issued not to ensure the safe passage of the bearer through an alien land, but to grant the bearer permission to leave his home territory for a defined period (something akin to a modern-day exit visa).

(We mentioned earlier how rulers in earlier times were usually more concerned with keeping people in than out).

What is believed to be the oldest surviving passport is a good example of one of these letters of permission. It dates back to 1636, belongs to a man called Sir Thomas Littleton and was signed by King Charles I of England.

On the single sheet of paper the king grants Littleton (who was accompanied by four servants) permission to "passe out of this our realme into the part beyond the Seas, there to remayne the space of three yeres".

Early passports have taken forms other than letters too.

In the medieval Islamic Caliphate, people's tax receipts functioned a bit like a modern-day passport, as only those that had paid their taxes were permitted to travel. (Even today, if you owe the IRS a large amount of tax, you may be unable to apply for a new US passport or renew an existing one).

To travel throughout the Roman empire you only needed to possess a "verbal" passport to be guaranteed safe passage; as long as you were able to utter the latin words "civis romanus sum" ("I am a Roman citizen") you would usually be fine.

At some point along the line, these letters and safe conduct passes started being referred to as "passports", the same term in use today.

The term was already in use in England by the year 1540, when King Henry VIII's Privy Council (which was in charge of advising the monarch) took charge of the task of issuing travel papers.

As for word's origin, it most certainly comes from the Middle French term "passporte", although it's still not fully settled whether this term originally referred to a document that authorized the bearer to pass through a gate in a city wall ("porte" is a french word that means "door" or "gate") or to pass through a maritime port to enter or exit a country.

Passport controls were abolished in the aftermath of the French Revolution in 1792 (such controls ran counter to the ideals of liberty), but were then quickly re-established due to growing fears of invasion by the émigrés that had fled France to other countries in the years that followed.

For a period of about 30 years prior to the onset of World War I, passport controls were widely relaxed across Europe (as well as in North America) at a time when there were powerful governmental and commercial interests that lobbied for a free flow of goods, money and people to spur on the industrial revolution.

Another reason for the easing of controls was that the numbers of people travelling had surged due to the development of modern railway networks and steam boats, as well as a rising middle class of tourists with disposable income.

The administrative systems of countries were unequipped to handle such unprecedented volumes of tourists, so they simply abolished controls altogether. By 1914 passports were virtually eliminated across Europe, but then World War I arrived and messed up everything.

At the onset of World War I passport controls were rapidly re-instated across Europe once more due to rising fears of foreign spies and also as part of efforts to prevent skilled workers from emigrating.

The Berlin wall, which was erected to prevent skilled professionals from fleeing communist East Germany for the democratic state of West Germany, is a prime example of the latter.

In 1920 after World War I had ended, the League of Nations held a conference in Paris, where it was decided that the world would adopt a uniform passport standard, which gave birth to the passport in the format we use today.

In the conferences that followed over the next few decades there were discussions about abolishing the passport and restoring the pre-war regime, but it was concluded each time that global conditions had changed too much for this to happen.

Britain got its first modern passport in 1915, although the document was only a single page that folded out and was sandwiched between cardboard covers. In 1921, blue passports in the form of a 32-page book were introduced and were written in French.

Security features in passports, like watermarks, barcodes and laminated photos, only first began to appear around the 1970's.

Malaysia was the first country in the world to issue biometric passports fitted with RFID chips in March 1998. Other countries soon followed suit by launching biometric passports, although many African countries and others have yet to implement them.

In the last two decades we've seen other important developments in many countries like automated border control systems (e-Passport gates) and the ability to renew passports online.

In the not-so-distant future, the world may do away with passports altogether and identify travellers solely by their individual biometric data, although that would be a brave new world indeed.

This timeline summarizes the history of the UK passport quite nicely.

So, we can see by looking back at the history of the passport that people did not always live under a hierarchical system of international movement controls as they do today.

Even the rise of the nation state following the French Revolution, there was a glorious interval prior to World War I when restrictions were lifted across Europe and freedom of movement prevailed.

But fear and distrust quickly took hold again during World War I and this time, they abided.

Governments had discovered a new source of revenue by issuing passports and visas and did not want to relinquish their new-found powers of population control. It's seemingly easier to erect fences than to knock them down.

As long as the zeitgeist is that of fear and distrust, concerns for security will continue to trump those for liberty and the walls will stay up.

So it seems that passports and visas are here to stay for a while, at least until the day when the nations of this world can learn to trust each other once more and are ready to take down their walls.

When you think of visas, you generally think of a permit that is required to enter a country and conduct specified activities within it. You don’t normally think of a visa as something that’s required to leave a country.

But although rarely heard of, there actually is such a thing as an exit visa.

For example, expats that have been living and working in Saudi Arabia and who now wish to permanently leave Saudi Arabia or leave their current employer and come back on a new visa, must first apply for and be granted a Final Exit Visa.

One of the mandatory documents for this visa is an NOL (non-objection letter) from the worker's employer/sponsor, which means that employees must get their sponsor’s consent for them to be permitted to exit Saudi Arabia.

Qatar is another country where expatriate workers require an exit permit to leave, although here some recent changes in legislation have made it possible for most migrant workers to now apply for their own exit permit, where previously they were at the mercy of their employers or sponsors to apply on their behalf.

Exit visas may also be required to depart some countries in the event of overstaying a visa.

For example, if you overstay your Russian visa, instead of simply being thrown out as would happen in most countries, you have to apply for an exit visa to be allowed to leave, and this is normally done at a local OVIR (office of visas and registration) office and can take up to five days.

But provided that you play by the rules, exit visas are something that you’ll almost never have to think about as a typical tourist or traveller in today’s world.

Somewhat related to the exit visa, you may also very seldomly come across the mandatory departure tax.

When leaving Bangladesh for example, anyone not exempted has to pay a compulsory departure tax, which can range from 500 BDT ($5.94) to 2,500 BDT ($29.70), depending on the traveller's destination and the means of exiting the country. Until you’ve paid this tax and presented the payment receipt you simply won’t be entertained at the immigration desk.

Visas are always issued for a particular purpose. Since people travel to countries for multifarious reasons, there is a multitude of visa types or categories offered by Governments.

Some people travel abroad for leisure, some for business, some to visit friends and relatives, some as pilgrims to visit sacred religious sites, some to proselytize, some to get cheaper dental care, and so on. There are visas for all these purposes.

The exact visa category that you need to apply for will depend on the main purpose of your visit, what you plan to do while you’re in the country and how long you plan to stay there for.

What follows is a list of the visas that will be of most interest to travellers looking to get a flavour of a country by visiting for a brief period.

The most commonly obtained visas from the ones listed below are undoubtedly tourist visas and business visas, but for the sake of completion we have listed all the visa types that may be of interest to short-term travellers.

Note that there are other visa types, including immigration visas, pensioner visas and spouse visas that we will not be discussing here, as those will be more relevant to expats or those looking to settle in a country than general tourists or travellers.

Transit visa

A transit visa grants you permission to transit through a country or airport (known as an airside transit visa) on the way to another destination.

This type of visa is usually valid for a short period ranging from a few hours to several days; just enough time to allow you to successfully complete the transit.

Transit visas are commonly issued to pilots, airhostesses, truck drivers, train drivers, bus drivers, ship captains and crewmembers of seagoing vessels for the purpose of fulfilling their duties while present in a foreign country.

As a traveller you may require one if you need to change airports to catch a connecting flight during a multi-leg journey, or even to catch a connecting flight from a different terminal of the same airport.

Tourist visa

A tourist visa is typically a short-term visa that grants an alien permission to travel in a country for leisure or to visit friends and relatives that reside there.

Business activities and remunerated work are normally not allowed on a tourist visa. Working online with a tourist visa, however, is a grey area and many travellers do it with impunity, even though it technically might be considered working.

Many countries will permit volunteering activities on a tourist visa, although there is often a stipulation that there most no gain or reward.

The maximum allowed duration of stay in a country for the holder of a tourist visa typically ranges from 15 days to an entire year.

India now even issues a 5-year, multiple-entry eVisa, but requires that you exit the country either every 180 days or every 90 days (depending on your nationality) during the validity period of the visa.

If you’re wondering which other countries offer tourist visas with generous maximum stay durations, refer to this list of countries with long visitor visas for travellers.

Note that some countries, such as Libya, do not issue tourist visas at all, although there are loopholes in these cases. Even Saudi Arabia only recently started issuing tourist visas on the 27th September 2019, for the first time ever. Along similar lines, you might also be interested in reading this article about the world’s most difficult countries to visit.

Although tourist visas are not designed for people wishing to reside in a country long-term, many expats have used loopholes like border runs and visa runs to live in countries like Cambodia and Thailand for years on end. We discuss more about border and visa runs further below.

Business Visa

If you are a travelling mainly for business, a business visa will grant you permission to engage in business-related activities in a country.

These activities could include establishing new business contacts, exploring opportunities to establish a new business venture, attending meetings, events and conferences, recruiting staff, negotiating and signing contracts, attending in-house training with a company, conducting trade, attending interviews and more.

A business visa does not however normally permit you to work or to seek gainful employment in a country. For that you would normally need a work permit or employment visa (see below).

Different countries have different rules for what you can and can’t do on a business visa so always verify your entitlements on a case-by-case basis to avoid crossing onto the wrong side of the law.

A business visa is usually more expensive than a tourist visa and is typically harder to obtain, since it will normally require you to have received a letter of invitation from a foreign business partner or professional organization.

Digital nomad visa

With the digital nomad lifestyle becoming increasingly common, many countries are beginning to recognize the demand for a special visa that will permit travellers to travel or live in a country while freelancing online or working remotely.

However, even in 2020 there is no specific digital nomad visa, although Estonia seems to have plans in the pipeline to launch such a visa in the near future.

Medical visa

A medical visa is issued to people who are travelling to a foreign country to receive medical treatment or to undergo testing or diagnosis.

Often, people will travel to foreign hospitals, dental clinics and other medical facilities to undergo surgery, get important dental work done (dental tourism) or to get fertility treatment (fertility tourism) when such procedures overseas are cheaper or better, or both.

Citizens of underdeveloped countries travelling to affluent countries for medical treatment usually do so to avail of the superior facilities and medical care, whereas citizens of affluent countries travelling to underdeveloped countries for treatment are primarily looking to save money.

Missionary visa

A missionary visa is normally issued to people that are visiting a country for religious reasons or for the purpose of carrying out missionary work through an organization within a country.

Usually a missionary visa would be issued to Christian missionaries (since missionary work is most associated with Christianity), though Islam and Buddhism are also usually classified as missionary religions (as opposed to non-missionary religions).

Note that missionary visas may not be issued by non-secular states with an official religion that’s different to the one being promulgated by the missionary or by states that don’t tolerate freedom of religion.

Some countries may require a letter of invitation from the host religious organization that states their relationship to you and your reasons for visiting the country.

In practice some Christian missionaries may visit countries while holding tourist visas instead of applying for a proper missionary visa, as has been happening in India for example.

Pilgrimage visa

This type of visa is issued to people who are planning to visit specific religious destinations in a country as a pilgrim.

Saudi Arabia for example, issues the Hajj (specific dates) and Umrah (more flexible dates) pilgrimage visas to Muslims that wish to make a pilgrimage to Mecca.

Pakistan also issues pilgrim visas for Sikhs that have permanent residence in a country other than India and for foreign nationals of Indian origin of 175 eligible countries.

India also issues a pilgrim visa to large groups of (10+) pilgrims wishing to visit holy places in India. With this visa you are only permitted to travel as part of the group and are not allowed to leave the group and travel on your own.

Private visa

A private visa is most frequently encountered with regards to a private Russian visa. This type of visa allows you to visit friends or relatives that are Russian citizens or foreign citizens with legal residence in Russia.

One of the requirements when applying for this visa is a private invitation letter from your Russian friend or relative, or foreign friend or relative legally residing in Russia that wishes for you to visit them.

This article covers the full details of this visa.

Bhutan issues a similar visa called a personal guest visa, which seems to be one of the few glimmers of hope for travellers wanting to circumvent the exorbitant and mandatory (for most nationalities) $200+ daily tourist tariff to visit the country.

Unfortunately this visa is not so easy to obtain, as among other stipulations, you need to have a Bhutanese contact that can apply for the visa on your behalf, and they must have been acquainted with you outside Bhutan for a period not less than 6 months.

I do however have a German friend who became acquainted with a Bhutanese girl during his travels in India and who was able to successfully obtain a personal guest visa through her.

Working holiday visa

This type of visa is designed to give young people (normally aged below 35 or 30) the opportunity to travel in a country for 1-2 years while also undertaking some short-term paid employment in the country in order to top up their travel fund. Working holiday visas often operate on a reciprocal basis.

The Australian Working Holiday Visa is probably the best-known WHV and is very popular with young backpackers aged 18-30, who can use the visa to travel and work in Australia for up 1 year.

With this visa you can work with any single employer for up to 6 months at a stretch and if you undertake 3 months of specified work during your 1st WHV you can even apply for a second WHV visa, thus extending your trip by another 12 months.

Citizens of some countries including the US can’t apply for the Australian Working Holiday Visa but can instead apply for the Australian Work And Holiday Visa, which is similar in many ways to the former type of visa.

Apart from Australia, working holiday visas are issued by a long list of about 40 other countries.

An eTA is not really a type of visa at all.

The acronym stands for electronic travel authorization and it’s a kind of online pre-screening that visa-exempt travellers have to go through when they are travelling to a country or transiting through it, usually by air.

eTAs generally make the screening process much quicker and easier than applying for a visa.

In Canada, for example, an eTA is required if entering or transiting by air. It costs just $7 CAD and all that’s required to apply is a valid passport, a valid debit or credit card and an e-mail address.

If approved (which typically happens in a matter of minutes but can take longer) the eTA is valid for 5 years (or until your passport expires, whichever comes first) and you can visit Canada as often as you want during that period for stays of no longer than 180 days at a time.

Other countries that have an eTA system in place for visa-exempt nationals include the US (ESTA or Electronic System for Travel Authorization), Australia, Argentina and Sri Lanka.

Visas can be issued by various methods. The ones that are available to you will depend on the country issuing the visa, your nationality and the type of visa you are applying for.

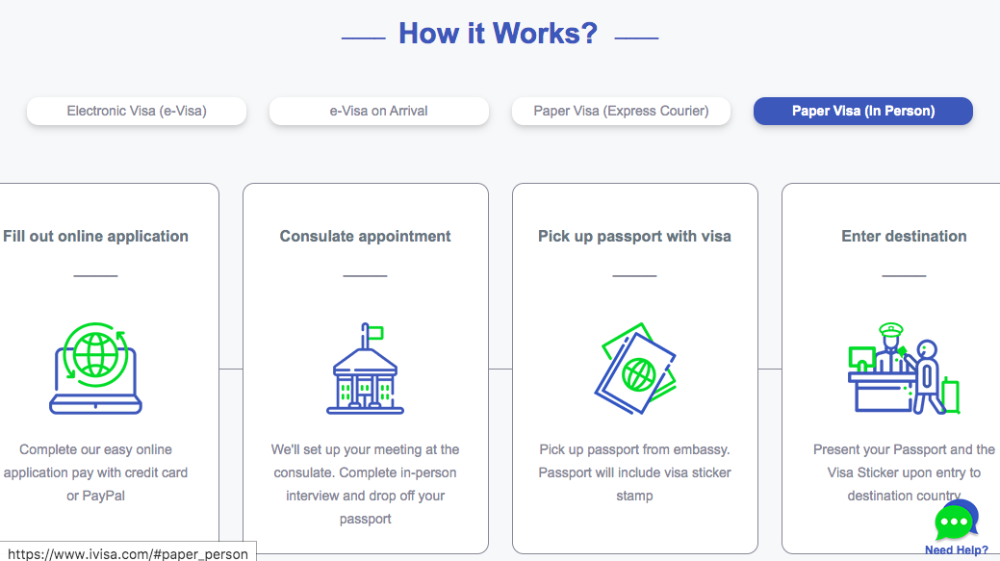

Embassy or consulate

Virtually every Government will issue "paper visas" through their embassies or consulates and these have always been the default channels for submitting visa applications.

In some cases, you will only be able to apply for a paper visa through an embassy/consulate located in your country of citizenship or country of residence.

Nonetheless, there are many visas that can be applied for in a country other than your home country. This is known as applying as a "third country national."

Whether you can do this or not will depend on whether the embassy entertains "third country national" applications by citizens of your country.

I have successfully applied for many visas at embassies outside my home country, such as the 59-day Philippines Tourist Visa that I obtained at the Embassy of the Philippines in Bangkok, Thailand, and the 1-year, multiple-entry Indian Tourist Visa that I obtained from the Embassy of India in Vientiane, Laos.

If you are from a very disadvantaged country with a weak passport, it’s likely that the vast majority of visas will only be issued to you through embassies and consulates, and the visa issuing methods listed below will seldomly be available to you.

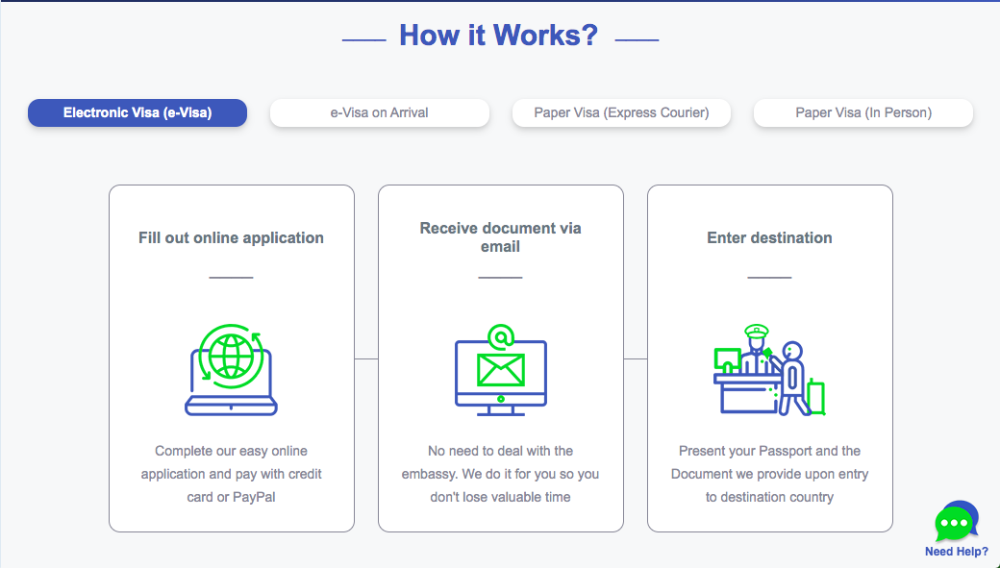

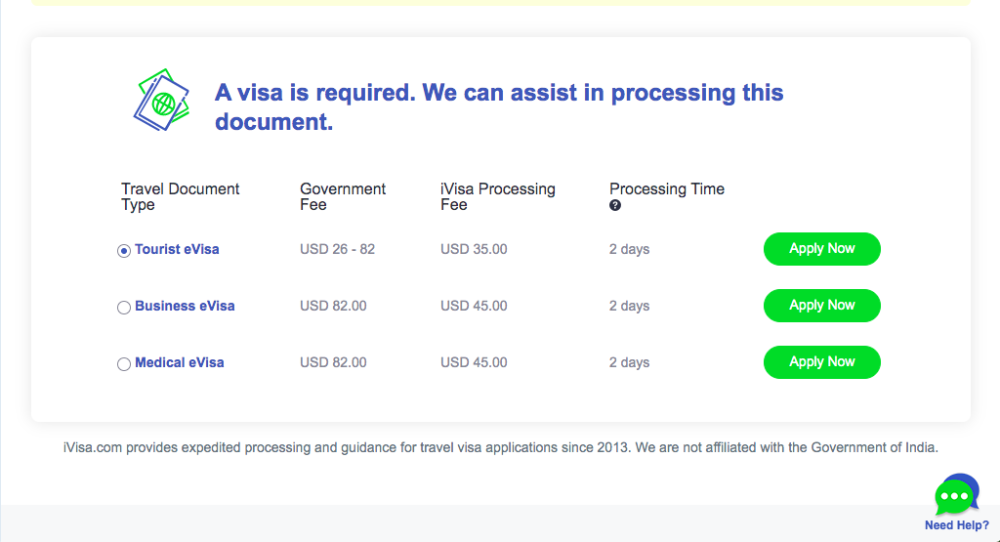

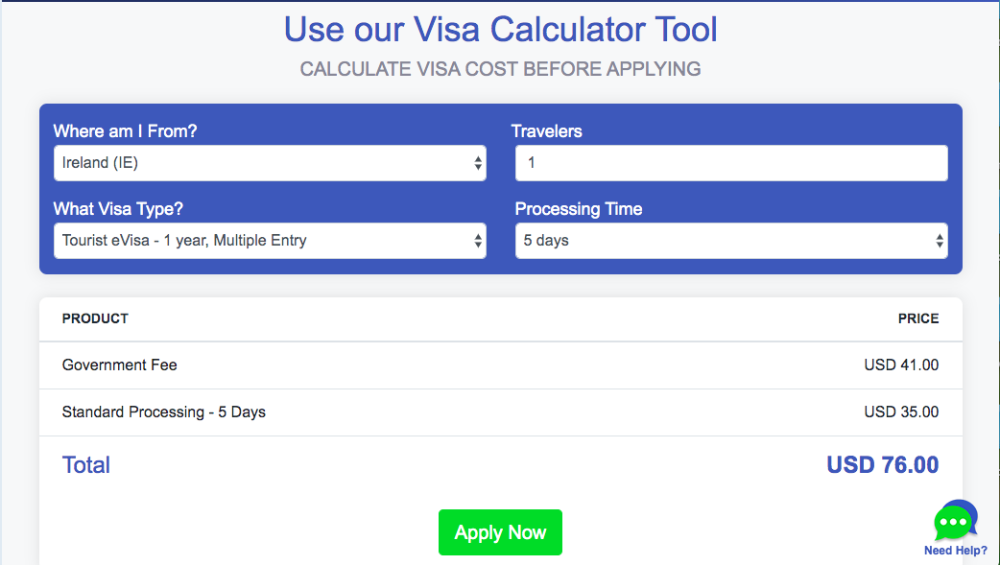

E-visa

Some countries now also issue electronic visas or e-visas to certain passport holders.

E-visas are intended to make the application process more convenient, as they are applied for, paid for and issued entirely online.

Although the online e-visa application process can still cause many a headache, it’s definitely an advantage to not have to courier your passport or show up at an embassy or consulate in person.

If your e-visa application gets approved, you generally get an e-visa approval letter sent to your e-mail as a PDF, which you need to print out and present at immigration upon arrival at the airport or land border checkpoint of the country you’re visiting.

E-visas are usually designed to facilitate travellers who only want to pay a brief visit to a country (if someone is only staying in a country for a short period, it won't be worth their while to endure a long-winded, rigorous application process at an embassy or consulate).

Hence most e-visas will be single-entry with a maximum allowed stay of 15-90 days and will normally cost under $50. There are some exceptions of course; India, for example, now issues a 1-year and 5-year e-visa for $40 and $80 respectively.

To learn more about all the e-visas that are currently available, you can refer to Nomad Capitalist’s list of all 24 of the world’s countries that issue e-visas.

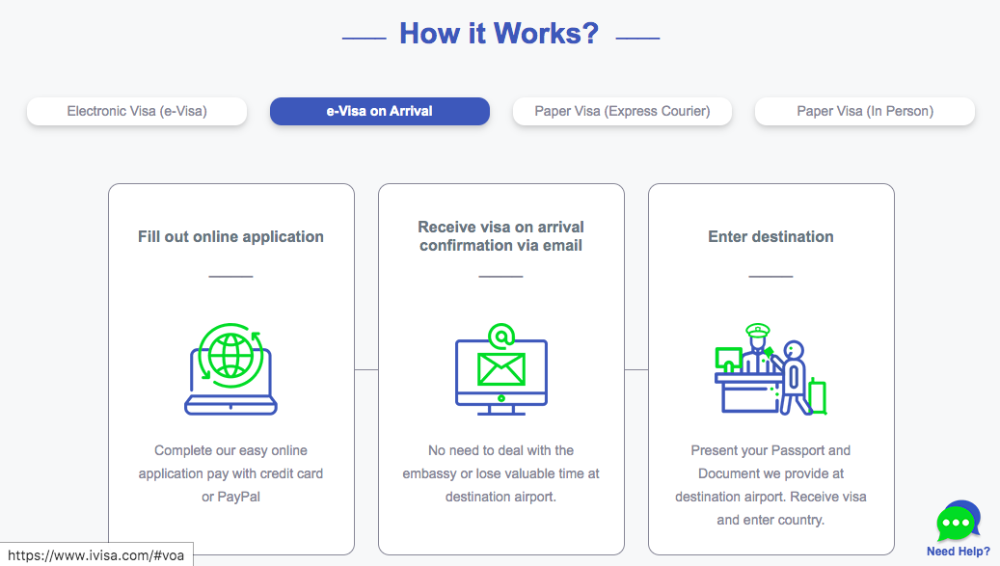

Visa-on-arrival

A visa on arrival means that the visa is issued on the spot when you arrive at one of a country’s airports or land border checkpoints.

Nationals with strong passports will typically have visa-on-arrival access to more countries than those with weaker passports.

Being eligible for a visa on arrival normally means that you can book a flight to a country on the spur of the moment, without having to apply for a visa in advance, whether online or at an embassy or consulate.

As with e-visas, visas on arrival generally cater to travellers that are coming for a short visit and who want a quick and convenient visa solution. Hence, like e-visas, most visas on arrival tend to grant maximum stays of 15-90 days and are usually single entry.

For the Vietnamese visa on arrival, which is a bit of an unusual case, you have to present an approval letter (signed and sealed by Vietnamese immigration) at the airport on arrival.

This approval letter can only be obtained by completing an online application beforehand and paying a fee to one of the numerous visa agents that are authorized to apply for the letter on your behalf.

In most cases however, a visa on arrival works just the way you’d expect it to; when you arrive at the airport you proceed to a special visa-on-arrival counter where you need to submit your passport, documents and fee for the visa.

You’ll probably have to queue behind other applicants for a while until you reach the counter. Upon handing everything in at the counter you might be assigned a number, which will be displayed on a screen or called out when it’s time for you to collect your passport with the new visa in it.

Sometimes there will be two different queues at the airport for those applying for a visa on arrival. One will be a normal queue and the other will be an express or express or fast-track queue where you can pay a little bit extra to have your visa processed more speedily.

During our travels in Southeast Asia, we visited many countries by getting a visa on arrival at airports or land border crossings; Indonesia, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Indonesia and Vietnam all offer this visa issuing option to certain nationals.

Note that there can often be restrictions on which ports of entry will issue a visa-on-arrival; Vietnam, for example, only issues one at its six international airports.

Do also be aware that land border checkpoints are generally quieter than airports and you may be given more individual attention and be subject to additional scrutiny when applying for a visa on arrival at one.

.jpg)

The answer to this question depends largely on your nationality and is also not set in stone, since visa rules are in a constant state of flux.

Reciprocity can also help to explain certain visa relationships between countries, which means for example that if country A allows country B's citizens to visit it without a visa, then Country B will often follow suit and allow Country A's citizens to visit it without a visa too.

One thing that's certain is that if you are a citizen of an affluent, developed nation, you will most likely have visa-free access to many more countries than citizens of underdeveloped countries with struggling economies.

You will also have e-visa and visa-on-arrival access to more countries, which, although not quite as convenient as having visa-free access, will allow you to travel to those countries on a whim without having to jump through all the usual bureaucratic hoops like embassy visits, lengthy paperwork and interviews.

A factor known as passport power comes into play here. Passport power is how much global mobility your passport grants you and it’s normally determined by how many countries you can access without having to obtain a prior visa.

According to the Henley Passport Index, which ranks passports based on how many countries their holders can access without having to obtain a visa in advance, the Japanese passport is currently the most powerful passport in the world, permitting holders to access 191 countries either visa-free or by getting a visa-on-arrival.

Following Japan is Singapore (2nd) and Germany (3rd). Tied 4th are Italy, Finland and, while Spain, Luxembourg and Denmark are tied in 5th position. Other European countries dominate the next 5 positions, though the US and New Zealand do also feature in the top 10.

At the very bottom of the Henley ranking index is the Afghanistan passport, which grants visa-free or visa on arrival access to only 26 countries. Just above it are Iraq (2nd weakest), Syria (3rd weakest), Pakistan & Somalia (tied 4th weakest) and Yemen (5th weakest).

Another well-known passport ranking tool that uses a slightly different system and ranking criteria is The Passport Index.

It assigns 199 passports a passport power rank that is primarily based on the passport’s overall mobility score, where passports accumulate one point for every country they can access without a visa or with a visa on arrival.

Unlike in the Henley Passport Index, no two passports in The Passport Index share the exact same ranking, and additional criteria like the passport country’s UN Human Development Index are used as the deciding factor for passports that tie in terms of their mobility score.

This ranking tool disagrees with Henley Passport Index that Japan is the world’s most powerful passport and pegs the UAE as the world’s strongest passport, assigning it a mobility score of 179.

Following the UAE in The Passport Index’s ranking system is Germany (2nd), Finland (3rd), Luxembourg (4th) and Spain (5th), which all possess the same mobility score of 172 but are separated according to their UN Human Development Index.

The weakest passport according to The Passport Index is (again) that of Afghanistan, with a mobility score of just 35, and just above it are Iraq (37), Syria (40), Somalia (41), Pakistan (42) and Yemen (44).

Whichever passport ranking system you abide by, you’ll notice that most of the countries at the bottom of the ranking ladder are middle-eastern, all are Islamic-majority nations, and these are also some of the world’s most dangerous countries to visit, with most Governments warning their citizens to steer well clear of them.

If we zoom out a little and look at the bigger picture, we can see that the majority of the world’s powerful passports belong to citizens of countries in Europe, North America, South America and Oceania.

Most African, Middle Eastern and Asian countries have weak passports, with the notable exceptions being the highly developed countries like Japan, South Korea, Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei.

In summary, it may be easier for citizens with weak passports to remember the answer to the question: which countries do I not need a prior visa to visit?

Whereas for those fortunate enough to possess a strong passport, it will probably be easier to remember the answer to the question: which countries do I need a prior visa to visit?

.jpg)

If you’re a citizen of a developed country and are in possession of a strong passport, it’s very likely that you can visit virtually every country in the world. For a sizeable number of them you won't even need a visa and for the rest you'll be admitted once you've obtained a visa.

But if you have a weak or unfavourable passport, you may find that some countries have completely prohibited entry to citizens of your country and they will not be issuing any visas at all to anyone of your nationality.

For example, nationals of disputed or unrecognized territories like Abkhazia, Artsakh, Northern Cyprus, Somaliland and South Ossettia are banned from entering almost every country in the world.

Israeli citizens cannot enter Algeria, Bangladesh, Brunei, Iran, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Syria, Yemen and Iraq (except for Iraqi Kurdistan), because none of these countries recognize the state of Israel. That makes the Israeli passport one of the most useless.

Malaysian citizens have been banned from visiting North Korea by their own Government since September 2017, due to safety concerns.

Taiwanese citizens cannot enter Georgia, as the country does not recognize their passport. This is the only country in the world the Taiwanese can’t visit.

Armenian citizens and citizens of other countries that are of Armenian descent are banned from entering Azerbaijan due to a state of war between the two countries

Nationals of Kosovo are refused entry to 19 countries, namely Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Cuba, Georgia, Hong Kong, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Lebanon, Moldova, Russia, Seychelles, Syria, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, Uzbekistan and Venezuela, since their passports are not recognized as legitimate. They can only enter Serbia with the Kosovo ID card, but not with their passports.

There are many other similar examples on this Wikipedia page, as well as examples of situations where visas are highly restricted or only issued under special conditions, like for making pilgrimages or visiting relatives.

When travelling in a primary country for an extended period, it is natural to want to undertake occasional jaunts into neighbouring, secondary countries.

For example, people that travel in India for 6 months or a year often like to temporarily leave India (often overland) to visit one of India’s bordering countries, such as Nepal, Pakistan, Bhutan, Bangladesh and Myanmar.

But the question is, can you do this without invalidating your existing visa, presuming of course that you are re-entering the primary country within the validity window of the visa?

The good news is that yes, you can indeed exit a country and re-enter it once or even multiple times, provided that your visa allows for multiple entries.

Visas may be single entry, double entry or multiple-entry, with the latter two entry types usually being more a bit more expensive than the single entry type.

A single entry visa permits you to only enter a country once. After you exit the country, you will not be able to re-enter, even if you are still within the visa validity period.

A double entry visa allows you to enter a country twice during the visa validity period. Hence with this type of visa you could enter the country for the first time, exit it and then re-enter it once for a second period of stay.

A multiple entry visa allows for multiple exits and re-entries during the visa validity period. Usually there is no limit to how many times you can exit and re-enter when in possession of this kind of visa.

A concept that causes an awful lot of confusion that results in a lot of questions being asked in public forums, is that of the validity period of a visa, as well as the meaning of the expiry date printed on the visa sticker.

So what is meant exactly, by the “validity period” of a visa?

Well, it can actually mean two slightly different things, and that’s why it has caused so much confusion for travellers.

For some visas (usually the single-entry type), the “validity period”, as typically defined by the issue date and expiry date, is the window of time during which you are permitted to enter the country, but does not specify the date you must leave by.

In other words, if the visa is “valid” for 90 days, from 01/02/’20 until 01/05/’20, this means that you may enter the country (use the visa) anytime within those dates.

With visas that define the validity period in this way, you do not have to be out of the country by 01/05/’20, as this is merely the latest date by which you may enter the country and has nothing to do with when you have to exit.

The latest date by which you must exit the country will not be specified by the dates given on the visa, but the visa will state a time limit like “60 days maximum stay duration” and the countdown will begin once you enter the country during the visa validity period.

An example where this definition of the validity period is used is with the single-entry, Bangladesh tourist (category T) visa.

The issue date and expiry date for this visa define the period during which you must use the visa (i.e enter Bangladesh) and then once you’ve entered the country you can remain there for a maximum of “X” days, depending on your nationality.

But for other visas (usually the long-term, multiple-entry type), the “validity period” has a slightly different meaning.

For these visas, the two dates (issue date & expiry date) on the visa define the window during which you must both enter and exit the country.

So for example, if this type of visa is valid from 01/02/’20 until 01/05/’20, you are only permitted to be in the country in the period between those two dates.

If you were to enter the country on the 30/04/’20, you would have to leave by the end of the following day, the 01/05/’20, since in this case the expiry date of the visa refers to the latest date that you are allowed to be in the country.

An example of where this definition of the validity period is used is with the 1-year, multiple-entry, Indian, T-1 tourist visa.

With this visa, you can only be in India between the two dates (date of issue & date of expiry) stated on the visa. For my nationality there is an additional condition that each stay in the country cannot exceed 90 days, though some other nationalities can stay for up to 180 days each time.

So I can enter and exit India as many times as I please during the 1-year visa validity period, but I must not still be in India after the date of expiry of the visa.

So to wrap up then, the validity period of a visa sometimes refers to the window you may enter a country, and other times it refers to the window during which you are permitted to be in a country.

Often, while you’re travelling, your original plans change.

You’re enjoying your trip so much that you decide you want to stay longer than your visa allows, or all flights from the country are cancelled due to some natural or man-made calamity and you won’t be able to exit before your visa expires.

In these types of situations, it would be handy if you could extend your visa. But is that ever possible?

The good news is that yes, many visas can be extended, though not all.

However, even visas that are supposed to be “non-extendable” will often be extendable given extreme circumstances such as a stolen passport or a medical emergency.

I was able to get my normally “non-extendable” Indian 1-year, multiple-entry tourist visa extended by 1-month during the COVID-19 (coronavirus) pandemic, when it was becoming difficult to travel within or out of India due to borders being closed and everything getting shut down.

Examples of visas that are officially extendable are the Indonesian 30-day Tourist VOA, the Cambodian 30-day Tourist VOA and the Thai 60-day Tourist Visa, which can all be extended by a further 30 days.

Technically with all these visas, you aren't extending the visa expiry date, since that only refers to the date you need to enter the country by. You're actually just extending the maximum number of days that you're permitted to remain in the country for.

For visas that are officially extendable, you can normally extend them by applying online or through an immigration office, and there will typically be a fee to be paid for the service.

One thing to watch out for with visa extensions is that you don’t leave it too late to apply, as the processing time can often be 7 days or longer.

If you apply late and your extension request ultimately gets rejected, you could find yourself illegally present in a country or having to book an expensive flight to exit the country at the last minute.

If you can’t get a visa extended, it may be possible to convert the visa into a different type of visa, so always bear that in mind as well. Some visas, however are both non-extendable and non-convertible.

A common mistake made by travellers is to think that if they are granted say, 30 days to stay in a country, that they can always leave the country exactly 30 days (720 hours) after the time they entered, without incurring any fine or other overstay penalty.

Let’s say a traveller first enters a country at 4 p.m on the 01/03/’20 and he is permitted to stay in the country for a maximum of 30 days.

He enjoys his trip immensely and returns to border control to exit the country a few minutes before the clock strikes 4 p.m on the 31/03/’20.

Since he technically hasn’t exceeded his 30-day stay limit, he is very surprised when the immigration official tells him that he has overstayed his visa and will have to pay a fine.

He argues and protests, explaining to the officer that the 30 days aren’t up until the clock hits 4 p.m today, but the officer just points to his computer, which is saying that the traveller overstayed his maximum stay allowance.

But why would this happen?

Because the day that the traveller arrived, the 01/03/’20, was counted as a full day that the traveller had stayed in the country, even though the traveller didn’t actually arrive until 4 p.m that day.

The system did not factor in the time that the traveller entered the country and by the end of that first day the system had decided that the traveller had already spent 24 hours or one entire day in the country, which meant that he was actually due to leave by midnight on the 30/01/’20.

So just remember that if you enter a country on a particular date, no matter how late in the afternoon or evening, always count that first day as a full day that you've spent in the country when working out when you have to leave by.

.jpg)

First of all, let us just say that you don’t ever want to overstay a visa if you can help it.

The first thing that happens when you overstay is…. absolutely nothing.

Nobody is going to be waiting for you at passport control glancing at their watch and wondering why still haven’t exited the country when your visa expires today.

It’s generally only when you go to passport control and the immigration officer begins to scrutinize your passport that the trouble begins.

In most cases, there’s a very slim chance that the officer will overlook the fact that you’ve overstayed, since it’s all computerized nowadays.

However, if you have a long-term, multiple-entry visa where, for example, each stay in the country must not exceed 90 days or 180 days, and you overstayed the 90 or 180 days limit, there’s probably a better chance that the officer won’t be aware of this rule.

When he sees that you are exiting the country within the validity period of the visa, he may mistakenly think that you haven’t broken any rules.

If you do overstay your visa, you may have a better chance of getting away with it if you depart the country via a remote land border crossing where the immigration staff are likely to be less experienced, especially when it comes to dealing with foreign passports.

The most experienced immigration officers are most likely to be posted at the country’s major international airports, so my advice would be to avoid airports if you’ve made a blunder.

But supposing you do get caught by the officer at passport control - what kind of negative repercussions can you expect to face for overstaying your visa?

Well, the harshness of the punishment for overstaying a visa will vary depending on several factors including the type of visa, your nationality, the country in question, the length of the overstay, the mood of the immigration officer and so on.

In many cases, you’ll be able to leave the country by paying the appropriate on-the-spot fine in cash (remember to bring exact change, because you may not be given any) for each day that you overstayed.

In Cambodia, for example, you can pay a $10 fine at passport control for each day that you overstayed.

Many people that want or need to stay in Cambodia for a couple of days longer than their tourist visa allows, will deliberately overstay and pay the $20 or $30 fine when exiting Cambodia instead of applying for a visa extension, which would have cost them even more than the fine.

In Thailand, the fee for overstaying is 500 baht ($15) per day, up to a maximum of 20,000 baht for an overstay of 40 days or more.

In India, the financial penalties for overstaying were recently increased, and now you can be fined $300 for any overstay up to 90 days, $400 for overstaying from 91 days to 2 years, and $500 for overstaying more than 2 years.

However, persons from minority communities of Bangladesh, Pakistan and Afghanistan only have to pay Rs. 100 ($1.32), Rs. 200 ($2.64) and Rs. 500 ($6.60) respectively, for the exact same offences.

Just recently we were exiting Bangladesh overland and crossing over into India after a 1-month trip.

Jili had exceeded her 30-day maximum stay limit by one day. The immigration officer told her that she just needed to pay a fine of 500 BDT ($5.91) and after doing so he stamped her out of the country.

But in countries where the overstay fines are small, the fines usually only get you off the hook for the first 30-90 days that you overstay.

If you overstay longer than that, you risk more severe consequences like being banished from the country for several years, deportation, heavier fines, imprisonment or a combination of these.

In Thailand for example, an overstay of 90 days or more could result in a 1-year ban, and an overstay of 5-years or more could result in a 10-year ban from the country.

Japan is notoriously strict for cracking down on visa overstayers. In 2004, a student from Washington who had overstayed his Japanese visa by just one day after completing a yearlong scholarship program at a Japanese university, was handcuffed and detained for 3 days, and received a 5-year ban from the country.

Even if you only overstay a day or two, you risk having a written note or stamp branded on your passport that identifies you as a rule violator, and that could increase the likelihood that you will be denied entry to the same country, or to a different country in the future.

The problem is that when you overstay a visa, you can never quite be sure what’s going to happen, and that uncertainty can cause a lot of unpleasant stress and anxiety in the run up to the time when you plan to confront passport control.

My advice is, just don’t do it.

We previously mentioned border runs and visa runs – loopholes in the system that have enabled many expats to live (and even illegally work or run businesses) in countries for long periods of time without having to apply for the proper long-term visas.

Border runs and visa runs are two similar, but slightly different things. Both of these phenomena have become strongly associated with Thai expats who are using them to stay in countries for years on back-to-back tourist visas or visa exemption stamps.

A border run is when a foreign national with an expiring visa or visa exemption stamp makes a trip to a neighbouring country via a land border crossing, solely for the purpose of immediately re-entering the country they’re exiting with a new stamp or visa.

Once the border runner has exited to the neighbouring country (for which they may need to have already obtained a visa in advance or may need to obtain one on arrival), they will typically make an abrupt U-turn and immediately attempt to re-enter the country they just exited.

In some cases the border runner might spend a couple of days enjoying the neighbouring country before trying to re-enter the original country.

Holders of long-term visas may also need to make occasional border runs in order to activate a new period of validity, since some long-term visas only permit a maximum continuous stay of 90 days or 180 days in the country, even if the visa is valid for an entire year or longer.

Border runs (exiting and re-entering a country either the same day or a few days later) are possible because many countries will issue a new visa-on-arrival or a new visa exemption stamp at land border checkpoints to many nationalities, even if they’ve just exited the country a few minutes prior.

Once back in the original country after completing the border run, the clock restarts from zero and a fresh period of stay is activated.

Although it usually refers to crossing overland by ground transportation into a neighbouring country and crossing back the same day, a border run could also made by air travel, which would involved flying into a neighbouring country and then flying back the same day or a couple of days later.

Typically people will use the border run strategy as a fairly easy and cheap way to extend their stay in a country by another 15-30 days. It avoids the hassle and often the expense of applying for a visa through an embassy or consulate.

The downside with border runs however is that after two, three or more consecutive border runs, immigration officials may begin to become suspicious and ask why you aren’t obtaining the proper visa that permits you to stay longer in the country.

Slightly different to a border run, a visa run typically involves making a short trip to a neighbouring country, either overland or by air, to obtain a visa for the country of interest from the relevant embassy or consulate in the neighbouring country.

A visa run might be made if an existing visa is about to expire and a new one needs to be obtained, or if the individual is currently visiting the country on an exemption stamp and now wishes to obtain a visa in order to extend their stay.

A visa run will usually take a bit longer than a border run (a few days typically), as documents will need to be submitted to an embassy or consulate and it will take time for the application to be processed.

The advantage with a visa run is that you can often apply for more long-lasting visas from embassies and consulates, so you won’t have to be back and forth like a yo-yo as much as a person doing border runs.

A rejected visa isn’t always the end of the world, and in many cases you may be able to immediately apply again a second time if your application was refused because of a minor technical issue.

In other cases, when there are more serious problems with your application, a rejected visa may mean that you cannot re-apply for the same visa any time in the near future, or at least not until your circumstances have changed considerably.

Even if you can re-apply immediately, a rejected visa can be costly, since you may have invested a lot of time into the application, paid a non-refundable visa fee and perhaps even had to cancel flights and hotel bookings that you had made assuming that you'd be granted the visa.

Subsequent attempts at procuring the same visa may also be less likely to succeed, since your application was refused the first time. Failure breeds failure. Success breeds success.

Therefore, just as prevention is always better than cure, it’s always better to do your homework beforehand to ensure that your application is bulletproof and that the consular officer has no good reason to reject your visa.

There are numerous potential reasons why your visa could be rejected and at the very least, you should be aware of the most common ones.

While visas can often be denied for reasons beyond travellers’ control, in most cases rejection happens when travellers make easily avoidable mistakes in their visa application.

What follows is a list of the common reasons for a rejected visa application:

Issues with application form

Sometimes travellers will take a chance and submit their application without being fully sure how certain parts of a form are supposed to be filled out, and then the inevitable visa rejection follows because the form was not completed in precisely the right way or some important details were omitted.

Here are some of the common issues with application forms that could lead to a visa rejection.

Incomplete form

Every section and every relevant part of a visa application form needs to completed by the applicant. Generally speaking, nothing should be left blank unless it is indicated that you should leave it blank.

Incorrectly filled form

The form also needs to be filled out correctly, in accordance with the form-filling guidelines provided on the government website or elsewhere.

Consular officers can be amazingly finicky about how forms are to be completed, and even an error as seemingly inconsequential as a word written in lower case letters (when it should have been written in block letters) or using a pen with the wrong-coloured ink (i.e using red ink when you were supposed to use black ink) could lead to a big red “X” being placed on your application.

Unfortunately, it’s not always obvious where to find the form-filling guidelines and some visa application forms can be very confusing and difficult to interpret without them.

For some visa application forms that I’ve filled out in the past I’ve had to look up step-by-step guides on the internet in order to figure out how to fill out certain parts of them.

Mismatching details

On visa application forms you’ll have to manually enter all the details on your passport, like your name, date of birth, passport number, issue date, expiry date and so on.

If there is any discrepancy between the details you put down on the application form and the details printed in your passport (even a single mismatching digit), your application could be rejected.

Other kinds of discrepancies could also kill your application. If, for example, you write down on the application form that your planned departure date is "X" but you submit a flight confirmation e-mail which shows that your exit flight is actually scheduled to depart on a different date "Y", your application might be standing on thin ice.

Issues with passport

Visas are often rejected due to issues with an applicant’s passport such as the following.

Damaged passport

A passport with torn pages, missing pages, a missing or damaged cover, lamination peeling off or even just general wear and tear is often the reason for a rejected visa. Protect your passport inside a leather passport cover, and don’t lose a visa because of a damaged passport.

Insufficient blank pages

Countries have different requirements for the number of blank pages your passport must have to be allowed to travel to a country.

Some countries require no blank pages, most require 1 or 2 blank pages, a few require 3 blank pages and then there’s Brunei, which requires 6 blank pages. Here’s a guide to how many blank pages various countries around the world require your passport to have.

Insufficient validity on passport

Many a trip has been ruined by travellers not being aware of a country's passport validity requirement.

One family who had planned a trip to Spain were forced to cancel their trip when their son was denied boarding because his passport had less than the minimum 90 days of validity beyond the date of the scheduled return flight.

Many countries require that your passport is valid for at least 1 month, 3 months, 4 months or 6 months, either beyond the date of arrival or beyond the date of scheduled departure from the country.

If you are applying for a visa for a Schengen state, for example, the rule is generally that your passport has to be valid for 3 months beyond your intended date of departure.

Some countries, however, only require that your passport is valid at the time of arrival or throughout the period of intended stay.

It is up to you to know the requirements of the country you're visiting. You can learn more by reading the "validity on arrival" section of this Wikipedia article, which summarizes the global situation with regards to passport validity requirements.

Issues with supporting documents

A list of specified documents always needs to be submitted along with any visa application. The list may be long or short, depending on how freely the Government is giving out visas to citizens of your country.

You’ll virtually always need to provide a passport photo or two (this needs to conform exactly to the specified dimensions), a photocopy of the bio-data page of your passport and a photocopy of your existing visa (if applying from a foreign country).

In many cases you will also be required to submit other documents like a printed travel itinerary, a confirmed hotel booking for your first night in the country and a confirmed exit flight (to prove you plan to leave).

Travellers from economically disadvantaged countries are more likely to be asked for documentation that proves they are in possession of sufficient funds to cover their expenses for the duration of their stay.

Accepted evidence is normally documentation like bank statements, pay slips, a bank loan in your name or a letter from a sponsor (if you have one),

Some visa applications may also require you to submit proof of being in possession of travel insurance.

If you are applying for a Schengen visa for example, you will need to able to prove you are in possession of a travel insurance policy with minimum emergency medical coverage of €30,000 (34,000 USD) for all of the Schengen states.

The most common issue with documents is that some of the mandatory supporting documents are missing from the application. If any documents are missing, you can expect a rejection.

The documents also need to be as specified. If your photos are the wrong dimensions or your passport photocopies are in black-and-white when they were supposed to be in full colour, this could also be cause for a visa denial.

Always run through a checklist before making a trip to the embassy to ensure you haven't forgotten any of the essential documents.

And don't become so focused on the long list of documents you need to bring that you forget to bring along your passport (it happened to me once).

False documents are also likely to lead to a visa being rejected. Obviously, if you're submitting false documents you shouldn't be too surprised if the application fails.

Issues with cover letter

Some visa applications will require a supporting cover letter, stating the purpose of your visit, your plans, travel dates, hotel bookings, flights, sponsors and any other relevant details.

Mistakes in the supporting letter are often cause for a declined visa.

Common mistakes here are poor spelling and grammar, illegible handwriting (if the letter was not typed), an incorrectly written address of the consulate or embassy, omitted travel details, no stamp or signature, and mismatches between the details in the letter and those in the application form.

Poor financial standing

Citizens of underdeveloped countries are particularly prone to scrutiny of their financial standing when applying for visas, although nationals of more wealthy countries may also occasionally have to submit documentation that proves they have sufficient funds to cover their trip expenses.

You probably won’t need to show a specified minimum sum in your bank account, but rather your ability to financially support yourself will be assessed based on the intended length of your trip, the estimated average daily cost, any income, savings, investments or assets you may have (you can present your payslips if you’re an employee), how much of your trip has been paid for in advance, any trip expenses that are born by a sponsor, and so on.

If your bank balance is low and you have to furnish a recent bank statement as one of the required documents for your visa application, be aware that it may not help if you get a friend or family member to transfer a generous sum of money to your account at the last minute, as this could be interpreted by a visa officer as a deliberate attempt to deceive.

If you are not reckoned to be financially sound enough by the consular officer, your visa will probably be rejected out of concern that you might become a liability to the Government.

Lying or withholding of information in visa application form

Visa application forms are designed to elicit as much information about applicants as possible, so that the Government can make a fully informed decision as to whether they want to admit a particular person to their country.

There may be certain questions on a visa application form where you feel it would be in your best interest not to give a truthful answer or to withhold certain compromising information.

For example, if you are asked whether you have ever overstayed a visa in the past and the reality is that you have, you might think it would be prudent to lie and say that you haven’t.

But although lying or not disclosing incriminating information can sometimes work out in an applicant’s favour, the Government will often be able to find out the truth anyway, and when they realize that you have not been fully honest and transparent in your application, you are very likely to have your visa rejected.

Although you may feel it’s counterproductive to answer certain questions on a visa application form truthfully, it’s generally still best to be as truthful and transparent as possible, unless you’re absolutely certain that there is no way the Government could find out if you’re lying or withholding information.

Insufficient ties to home country

Visas are much easier to obtain if you are able to demonstrate strong ties to your home country.

Ties are the physical and non-physical things that bind you to your native country, and could include things like a stable, well-paid job, your family or spouse, a property that you own or a business that you run.

It is particularly important for you to be able to prove that you have strong ties to your native country if you are citizen of a developing country that is applying for a visa in order to visit a more developed country.

This is because people from countries with struggling economies are far more likely to try to illegally stay back in a country with a better economy than vice versa, since the majority of people seem to want to heighten their income and economic prosperity rather than lower it.

Failure to prove stated purpose of visit

Visas are always issued for a particular purpose. If you are applying for a tourist visa, for example, you should be able to prove that you are visiting a country for the purpose of leisure and tourism.

Evidence that sightseeing or tourism is the purpose of your visit might include a printed travel itinerary, confirmed hotel, bus and train bookings, a pre-booked package tour, a travel insurance policy and so on.

If you are unable to convince the consular officer that your true purpose of visit is the same as the one stated in your application, your visa is liable to be rejected.

Botched interview

Not every visa application will see you called for an interview with a consular officer, but some will.

A botched interview due to nerves or a lack of preparedness has been the downfall of many a visa applicant.

The most common way that people screw up a visa interview is by not having confident, concrete answers to the officer’s questions. You need to be definite and exact, not vague.

Vagueness means uncertainty and an officer might interpret that to mean that you don’t really intend to leave the country at a later date.

A person I know had her US tourist visa rejected because during her interview at the US embassy the officer asked her what was her next move after visiting the US. Due to her nervousness, she told the officer that she wasn’t sure if she would return home after her trip to the US.

Although what she meant by this was that she might visit another country before returning to her home country, the officer interpreted this as a red flag because it sounded vague and she didn’t appear to have any concrete plan. The next news she received was that her application had been denied.

Another seemingly trivial thing that could be cause for a visa rejection is dressing inappropriately or too informally during the interview. If you waltz into the interview in your underwear, you might be needlessly jeopardizing your visa application.

With that being said, I did once successfully get my Indonesian tourist visa extended by 1 month in the city of Bandung, even though I showed up in my chequered boxer shorts (the weather was hot!) for the interview with the officer in charge.

So to maximize your chances of sealing the deal, make sure you turn up for the interview smartly dressed, with a concrete plan (even if it’s not your real plan) for the trip in mind, and ensure you know all the specifics of the trip off by heart, like the entry and exit dates, the trip length, the airlines you're flying with, the names of the cities you plan to visit and the order you plan to visit them in, the names of a few hotels that you plan to stay in, some of the activities you plan to do and so on.

Unfavourable travel history or criminal convictions

If you have a history of illegally overstaying visas, illegally entering countries without a visa or having visas rejected, or if you have a criminal record, or if all of the aforementioned apply to you, this will frequently be cause for your current visa application getting rejected, for obvious reasons.

On the other hand, a travel history that shows that you've visited lots of countries and never overstayed or given authorities any problems, should definitely work in your favour.

The first tourist visa that you apply for is always the one that's most liable to arouse suspicion, as authorities will wonder why you suddenly took up an interest in travelling for pleasure just now when you never showed any interest before.

Once you have a few visa stickers and stamps in your passport, it will be easier for authorities to believe "oh, he/she must be a traveller".

Applying outside the permitted window

Applying for a visa either too far in advance or too close to the date of intended travel could be another cause for your visa being rejected.

Most visas will have an earliest and a latest date before the date of intended travel that they can be applied for.

To use the Schengen visa as an example here again, the very earliest that you can file an application is 6 months before your planned departure date and the very latest that you can file an application is 15 days beforehand.

It’s crucial that you submit your visa application within the permitted window, or you could be looking at a ruined trip.

Existing visa is still valid

If you try to apply for a new visa before your existing visa has expired, and the validity dates of the new visa overlap with those of the existing visa, the application for the new visa may be refused.

However, rules can vary from country to country, and in some cases a new visa application where the validity period overlaps with the existing visa may result in the existing visa being cancelled.

Parallel visa applications

Applying for a particular type of a visa from multiple embassies and consulates in order to expedite the visa approval process will usually end up getting you nowhere in the end.

Likewise, applying for two or more types of visa simultaneously may end up in both being rejected.

You need to check with the relevant embassy to find out if it’s okay to apply for more than one visa at a time.

Invalid medical insurance policy

Proof of medical insurance cover is a mandatory requirement for some visa applications.

If you’re applying for a Schengen visa for example, you must have medical coverage of at least €30,000, as well as cover for repatriation and medical evacuation.

Russian visas are another example. Travellers belonging to any of the Schengen states have to provide evidence of a valid medical insurance policy when applying for a Russian visa.

Your visa could be rejected if the medical cover you buy is not valid for the entire duration of your stay, for the parts of the world you’re travelling to, or does not include the required coverage types and minimum claim limits.

External factors

Governments may cancel or suspend visas at any point in time as a result of threats to a country’s political or economic situation.

For example, in order to contain or slow the spread of a contagious virus, Governments may suspend all visas or only visas for travellers who are either nationals of, or have recently visited the most badly hit countries.

The required documents for a visa can also suddenly change overnight, as a result of changing bilateral relations, efforts to combat counterfeit applications, amendments to visa policies and so on.

Such changes may be in full effect for quite some time before being announced or published anywhere.

If you’re unlucky, you may have already submitted your application before such a policy change was disclosed, leading to a rejected visa.

The answer to this is yes, absolutely.

As we saw at the beginning, a visa means that your documents have been checked and you’ve been pre-approved to enter a country, but the final decision still lies with the immigration officer at border control.

You may be denied entry at passport control for many of the same reasons that we listed above for why your visa was rejected.

This is because some of the entry requirements may not be checked during the visa application process, but will instead be checked later when you are boarding the airline or when you reach the immigration desk.

Below we'll just focus on the most common reasons why travellers can still face difficulty getting past immigration even though they have already been granted a visa.

Port of entry is not viable

Most countries have multiple ports of entry.

Nations that share extensive land borders with neighbouring states may have dozens of land entry points, while most island nations will have at least a handful of international airports and seaports.

Just because all these ports of exist, doesn’t mean that you’ll be permitted to enter the country through all of them.