Heavenly Dzükou Valley: The Complete Guide To Visiting Nagaland's Hidden Paradise

"Here hills and vales, the woodland and the plain,

Here earth and water seem to strive again,

Not chaos-like together crushed and bruised,

But as the world, harmoniously confused:

Where order in variety we see,

And where, though all things differ, all agree."

- Alexander Pope

What if I told you there was a place in northeast India....

... a secluded valley nestled high in the mountains, where the rivers run clear and pure...

...where the air is fresh and invigorating...

...where multi-coloured wildflowers dance in the wind...

....and where the only audible sounds are the therapeutic murmurs of perennial brooks, the gentle rustle of bamboo leaves in the breeze and your own footfalls on the soft earth.

A serene retreat where you can go to escape the hubbub and helter-skelter of urbanity, an environment where there are no distractions or deafening dins to drown out the more subtle whispers of your own inner voice.

A place that is not only gratifying for those seeking quietude or spiritual fulfillment but also a perfect fit for adventure seekers, spelunkers, nature lovers, botanists, hikers, trekkers and explorers.

And what if I told you that this place is still largely untouched and unspoilt, and has yet to be discovered or visited even by many seasoned global travellers?

It sounds too good to be true doesn't it?

Yet, such a place does exist.

The place I'm referring to is known as the Dzükou valley and in this comprehensive travel guide, we're going to tell you everything you need to know to make the most of your visit to this sacred place.

This is an in-depth, 10,000+ word travel guide that covers the ins and outs of independently trekking to and experiencing the Dzukou Valley without the aid of a local tour operator.

However, the DIY approach definitely isn't for everyone.

If this seems too daunting a trek to tackle on your own, why not hire a professional local tour guide to lead you on a 2-day trek to the valley from Viswema village, with all meals, snacks, coffee/tea and trekking equipment provided. You can book that Dzukou Valley tour right here.

The Complete Dzukou Valley Travel Guide By Twobirdsbreakingfree

Table of contents

- What is the Dzükou valley?

- Location and hard facts

- Important background info

- West Dzükou

- The Dzükou valley ecosystem

- Tourism in the Dzükou valley

- When to visit the Dzükou valley

- How to get to the Dzükou valley

- The Viswema trail

- The Zakhama trail

- Where to stay in the Dzükou valley

- Option #1 - Stay in the rest house

- Which dorm building to sleep in?

- What about the VIP rooms?

- Option #2 - Bring your own tent and camp

- Option #3 - Sleep under a rock overhang

- Procuring food and potable water in the Dzükou valley

- Obtaining firewood and cooking your own meals

- Entry fees to Dzükou valley

- Renting camping equipment from the rest house

- Hiring a guide at the rest house

- 4 things to do in the Dzükou valley

- Conclusion

Watch Video:

What is the Dzükou valley?

The Dzükou valley, spanning the Nagaland - Manipur interstate boundary in northeast India, is a hidden paradise here on planet Earth. You can think of it as the Shangri-La of the northeast.

The valley is a breathtakingly beautiful, picture-postcard masterpiece of nature’s handiwork that more rightfully belongs in a fairytale book or fantasy novel than in this earthly realm.

Stretching as far as the eye can see in all directions, the Dzükou valley boasts an astonishing, undulating treeless sweep of knolls, hillocks, verdant glens, river-cut ravines, meandering rivulets and deep-reaching caves, all just begging to be explored.

The valley's picturesqueness largely derives from its interesting topography, which has been sculpted over millennia by the geological processes of weathering and erosion, and fully unveiled thanks to the almost complete absence of tree cover.

The convoluted folds, ripples and contours of the valley are a marvel to witness and few travellers will have ever observed anything like it before.

In addition to the jaw-dropping scenery, the other major drawcard the valley holds is its stunning exhibition of wildflowers of varying hues, a display that reaches its peak in the first two weeks of July.

Hence the Dzükou valley has also been dubbed “the valley of flowers”.

We recently visited the Dzükou valley during the month of December, in the midst of the winter season. Our brief but beautiful experience there left us feeling deeply moved and inspired.

If you happen to already be travelling in Nagaland, we would strongly counsel you not to miss out on the Dzükou valley, even if its remoteness and inaccessibility does present some logistical challenges in getting there.

It is one of the most sublime destinations in the northeast Indian state of Nagaland and indeed, in the entire Indian subcontinent.

The Dzükou valley lies between 25°31’0” N and 25°35’0”N latitude and 94°3'0"E to 94°5'0"E longitude, straddling the Nagaland-Manipur border in the southernmost reaches of Nagaland’s Kohima district, though the majority the valley lies on the Manipur side of the border.

The valley covers an area of about 27 sq. km and sits at an average elevation of about 2,452 m above sea level, which contributes to its isolation and helps to keep it secluded from the world of mere mortals down in the lower-lying hill areas below.

The highest peak in the Dzükou valley area is Mt. Iso (Mt. Tenipu) at 2994 m, which is also the highest peak in Manipur.

As the crow flies the valley lies about 14 km SSW of the central ground in Kohima, but the actual distance that must be travelled by road and then subsequently on foot to reach the valley is much greater than that.

According to Wikipedia, the word “dzükou” comes from the Viswema dialect of the Angami tribe and translates to “soulless and dull”.

A local legend tells of how the people from the nearby village of Viswema had tried to establish a new settlement in the valley, but their crops had failed to flourish due to the unfavourable weather and soils.

However other sources claim that the term “dzükou” is an Angami/Mao word that translates to “cold water”, referring to the ice-cold stream that flows through the valley.

There are many other myths and fables surrounding the Dzükou valley. For example, the unadulterated streams in the valley are believed by many to have curative properties.

Other legends tell of white elephants inhabiting the valley, of a secret forest in the valley that teems with wild animals and of a pulchritudinous but malevolent female spirit that takes the life of a male visitor to the valley every year.

Regarding the ownership of the Dzükou valley, there has been an ongoing intertribal dispute over the matter, which has resulted in both parties boycotting each other economically.

The dispute is between the Mao people of Manipur and the Angami people of Nagaland. Each side basically claims the entire Dzükou valley as their own territory.

This is not an inter-state quarrel about the Nagaland –Manipur borderline, but certain portions of the traditional territories of the two groups do incidentally overlap with the current inter-state boundary.

Historically speaking, according to one source, the Angami people controlled the Dzükou valley but the Mao people would access their land and harvest from it resources such as banana leaves, bamboo and cane. For this the Mao would pay royalties (taxes) to the Angami in the form of meat or other goods.

We haven’t visited the Manipur side of the Dzükou valley and therefore we won’t be covering it in this guide. This guide is all about the portion of the Dzükou valley that falls within Nagaland.

However, in Nagaland there are actually two different parts of the valley that people can visit, namely the west and south Dzükou areas.

Having never visited west Dzükou we know very little about this part of the valley, except that it is accessed by several hours of trekking from Khonoma village.

This impressive Angami village is known for being India’s “first green village” that has imposed an outright ban on hunting and logging in the surrounding forests.

West Dzükou receives fewer visitors than south Dzükou and is not as well known. This guide will only deal with south Dzükou but we will tell you an interesting story about west Dzükou before we begin the guide.

About 45 minutes to an hour by walking from west Dzükou there is a waterfall called Sanctuary Fall, which freezes over completely in the wintertime.

A Christmas tragedy unfolded at the foot of this waterfall at approximately 10:30 a.m on the morning of December 26, 2014, when six teenage students fell through a thin layer of ice into the depths of the frigid lake at the foot of the waterfall.

The ice had suddenly begun to break up when too many of the group members had walked out onto it at once to take and pose for photographs.

The six teens that fell through the ice were part of a twelve-member group that had gone to have a picnic together at the waterfall.

Three of the students managed to extricate themselves from the icy-cold water but the other three (a boy, his sister and another girl) lacked the ability to swim and they all drowned despite efforts by the other group members to rescue them with bamboo sticks.

A few of the group members rushed back to the village after witnessing the shocking incident and over 200 volunteers soon arrived with equipment to break the ice.

A few villagers then dived into the water in a bid to retrieve the bodies but it was too cold to risk spending more than a few seconds inside the water.

All the volunteers managed to retrieve were two caps reportedly belonging to the victims. By nightfall the retrieval attempt was abandoned but base camps were soon established in the area and efforts to find the bodies continued for days afterwards.

Expert divers came all the way from Wokha district to assist but were too afraid to dive into the ice-covered lake. Special army diving personnel were then called from Rangapahar near Dimapur to continue the search.

The divers were struggling to locate the bodies because of the surprising depth of the lake (over 40 feet) and there are rocks near the bottom that the bodies might have gotten wedged between.

Eventually, thanks to the determined efforts of all the volunteers and rescue workers, the water level of the lake was lowered several feet with the aid of pumps and pipes, and all three of the victim’s bodies were successfully retrieved, much to the relief of their bereaved, grief-stricken parents.

You can read the original story here.

Many bloggers who have previously visited the Dzükou valley have speculated about its origins, stating that it formed as a result of a meteorite impact or that is a caldera resulting from a violent volcanic eruption long ago.

However these assertions are most likely to be erroneous and available evidence points towards it being a simple geosynclinal valley formed by differential weathering and erosion of the Earth’s crust.

Some estimates put the age of the valley between 2 to 4 million years old. Geologically the rocks form part of the great Kohima Synclorium.

Many different types of rocks and minerals comprise the rock profile of the valley, including sandstones, clays, shales siltstone, petrified wood and lignite seams.

A cursory glance at the valley from afar might suggest that the terrain is clothed in lush, verdant grass, but that it is not the case at all; the valley is predominantly dressed in a type of dwarf bamboo, known by the botanical name of Sirundundinaria rolloana.

These bamboo plants so thickly in places that there can be more than six hundred plants growing within a single square metre of land.

A riot of wildflowers and blossoming rhododendrons graces the valley in the blooming season (April – September), with many rare and elegant species represented, such as the Siroi lily (Lilium mackliniae) and most notably, the endemic Dzükou lily (Lilium chitrangadae).

The Dzükou lily was first identified in the valley by Hijam Bikramjit of the Life Sciences Department, Manipur University, in the summer of 1991 and he named the flower after his mother.

The Dzükou lily flower is a deeper shade of pink than that of the revered Siroi lily, which also reportedly occurs in the valley. You can view an image the flower here.

As regards the fauna of the valley, it’s difficult to find any detailed studies or surveys online.

The finely plumaged Blyth’s Tragopan (Tragopan blythii) pheasant, designated as the state bird of Nagaland, takes refuge in the wooded pockets of the valley, though the exact size of the population here is not known.

The bird is unusual for its preference for dwelling at higher altitudes. However, the Blyth’s Tragopan is now greatly endangered in Nagaland due to hunting and snaring activities for its meat and feathers.

Habitat fragmentation due to deforestation in Nagaland also threatens the genetic diversity of the population because the birds won’t abandon their cover to visit other pockets of woodland.

Some writers also report the presence of Asiatic black bears (Ursus thibetanus), leopards (Panthera pardus) and Indian elephants (Elephas maximus indicus) in the Dzükou valley. We have been informed by locals that tigers are not normally found in the valley but may be present in neighbouring areas.

One of the biggest threats to the Dzükou valley ecosystem are wildfires that spread rapidly through the great swathes of dwarf bamboo cover. Fires are particularly liable to occur during the winter season, as can be seen by examining the history of previous outbreaks.

Wildfires in the valley are normally started by people, whether intentionally or unintentionally. Often all it takes is for somebody to carelessly toss an unextinguished cigarette butt or a smouldering match into the vegetation.

A huge fire broke out here in January 2006 and raged for over week. An estimated 70 sq. km of the Dzükou valley and adjacent Japfu hill ranges were devastated by the inferno.

Another, albeit less destructive wildfire struck the valley in January 2010, destroying 15 sq. km of forest cover. In February 2012 a conflagration reduced hundreds of acres of the valley to ashes. The most recent wildfire seems to have occurred in March 2015.

The problem is that wildfires destroy the existing diversity and patches of forest cover in the valley. Thriving on the burnt ground, the rapidly regenerating dwarf bamboo then assumes dominance, suppressing the growth of other competing species. Thus the fire-bamboo cycle is self-perpetuating.

In addition to fire, the precious wildflowers of the valley also face some degree of threat from collectors and specimen hunters. It is good practice not to pick too many flowers, especially ones that you deem to be rare.

Despite its inaccessibility, the Dzükou valley is one of the most popular nature and trekking destinations in northeast India. However, since Nagaland is already quite offbeat compared to many other Indian states, the valley only receives a small trickle of visitors.

For the time being at least, the majority of visitors to the valley seem to be domestic Indian tourists, and many of these come from far afield.

During our visit to south Dzükou we met a middle-aged couple from West Bengal, a solo male Indian traveller working as a software engineer in Bangalore and a mixed group that was mostly comprised of Asians, except for one Caucasian guy who appeared to have befriended the others.

For the time being at least, the Dzükou valley is not very well known among foreign tourists, or if it is, they're certainly not coming here in droves yet, probably because of the valley’s remote location and inaccessibility.

However, as we’ll soon see, developments are already underway that may change the current situation forever. The clock seems to already be ticking and it may only be a matter of time before the valley is debased irreparably by opening itself up to mass tourism.

.jpg)

The two driest times to visit the Dzükou valley are in the summer season (April – May) and the winter season (Nov – Mar), though regardless of when you visit, you’re guaranteed of a visual treat.

An advantage of visiting during the drier months is the absence of pesky, bloodsucking leeches.

If your dream is to experience an enchanting valley festooned with vibrant, nodding wildflowers, you ought to visit from April to September, as that is the blooming season when the wildflowers can be seen in their full glory.

We didn’t visit the valley during the flowering season, but most of the sources we’ve consulted state that its zenith usually occurs in the first two weeks of July.

However by July the monsoon season (June – September) will already be underway, trails will become muddier and slippier, and bloodthirsty leeches will be out in full force.

So just be aware that you’ll have to contend with that unwelcome nuisance. Bags of salt or spray bottles filled with brine will be your friend.

Visitors sometimes get stranded in the valley or washed away in flash floods when returning from the valley during the monsoon season too, which we’ve discussed a bit more under the section of this guide “How to get to the Dzükou valley”.

The winter season (October to March), which was when we visited, is not the best time for witnessing flowers but boasts a different kind of stark, desolate beauty.

In winter the valley loses its vivid green hue and becomes more straw-coloured because the green-pigmented chlorophyll breaks down in the leaves of the dwarf bamboo plants.

Meandering rivulets at the bottom of the valley freeze solid at night and begin to slowly thaw again after sunrise.

Delicate ice crystals form on foliage during the night and these can still be witnessed in the early morning before they melt in the heat of the sun. The only catch is that if you wish to witness them, you'll have to motivate yourself to get out of your warm bed before dawn.

These ice crystals can provide photographers with opportunities for some very unique and beautiful images.

The other major difference in winter is that the valley is even colder than usual. While we felt quite warm in the direct sunshine during the daytime, there was simultaneously an undeniable chill in the air that largely counteracted this. Air temperatures in the day during winter often hover around 10 °C.

At night air temperatures commonly plummet to several degrees below freezing and each morning we would wake up to see a heavy frost carpeting the entire valley. The blanket of frost would then vanish surprisingly quickly in the warmth of the morning sun.

One major benefit of the winter season is that leeches are absent, or least, we didn’t encounter any during three days of trekking in the area.

.jpg)

You may be wondering if a guide is necessary for trekking to the Dzükou valley.

Under ordinary circumstances, it is definitely not necessary, but you should read our instructions carefully because unprepared travellers do sometimes manage to get lost or take a wrong turn on the way.

If you still want to hire a guide, you can ask your hotel about the matter.

If you happen to be attending the Hornbill Festival when you decide to visit the Dzükou valley, it is possible to hire a guide through your campsite, if you happen to be staying in one.

We recommend you stay at Camp Zingaros, run by Discovernortheast.

The five guys from Discovernortheast who run the campsite are really helpful and can hook you up with a reliable guide to bring you to the valley at a reasonable rate of 1,500 rupees per day.

But as regards doing things independently, there are three main approaches to the Dzükou valley.

One of these approaches is a new five hour trekking route from Mt. Tenipu (Mt. Isii) in Manipur’s Senapati district was recently opened by MMTA (Manipur mountain and trekking organization).

However in this guide we will be dealing with the two Nagaland approaches to the valley, namely the Viswema and Zakhama trails.

Trekkers do occasionally get lost or take a wrong turn on both of these trails but if you carefully study the instructions we’ve laid out in this guide, you should be able to avoid ending up like one of those unfortunates.

The Viswema trail is the easier of the two routes, with only 1 hour of steep climbing. The majority of the route consists of relatively flat, easy trekking.

This will also be the shortest route for most people, provided you begin your hike from “Trekker’s Point”, which is located at the end of the motorable road, approximately 8 – 9 km from Viswema village.

If however you walk all the way from Viswema village, from the beginning of the motorable road, you’ll have to walk an extra 8 – 9 km just to reach the trailhead at Trekker’s Point and the hike will take more time than the Zakhama route.

To get to Trekker’s point, you need to first focus on getting to Viswema village, which lies approximately 23 km to the south of the local ground in Kohima on the NH39 road.

You have a few options for getting to Viswema.

Hitchhiking is not to be discounted if you can make your way to the city outskirts, but probably the most convenient way is to take a shared zonal taxi from the Networks travel AOS bus stop, which is marked on Google Maps.

Despite the name, this place seems to be more of a taxi stand than a bus stop and you’ll know you’re there when you see an arcing line of yellow Tata Sumos.

.jpg)

The vehicles depart only when they are full with passengers (usually 11 passengers in total: 3 in front, 4 in middle, 4 in back row), which can take a half an hour or more after they begin accepting passengers.

Try to avoid sitting at the door-side of the middle row because you will be disturbed by passengers entering and exiting the back row of the vehicle via the fold-down seat.

The journey to Viswema should take less than an hour and you’ll be dropped at the entrance gate to the village.

A minor road branches away from the main road here at the large Tsükru building opposite the village gate.

This is the roadyou’ll need to take but bear in mind that it goes on for a respectable distance of 8-9 km until it reaches the trailhead at trekker’s point.

We opted to walk this entire stretch of motorable road, thinking we'd hitchhike if a vehicle came along, but alas, we weren't so fortunate.

The long uphill walk consumed a lot of our energy reserves before we even reached the challenging steep section beginning at Trekker's point, and was also rather time-consuming.

If you’re planning to walk or hitchhike, add 2-3 hours to the journey time and make sure to set out early in the morning if you want to be guaranteed of reaching the rest house before nightfall.

If you don’t want to walk or hitchhike all the way from Viswema you should be able to charter (reserve) another Sumo from outside the village gate. There is often another Sumo lying in wait for trekkers when they arrive here.

Expect to pay 1,000 to 1,500 INR for this service, because the road is very bad condition and the drivers normally won’t go for less.

.jpg)

You can eat aloo puri (potato with deep fried flatbread ) in the little tea hotel here in the Tsukru building to fuel up for the trek to the valley.

The man in this shop also sells matches for 1 rupee per box and lighters for 10 INR each, which will both come in handy if you're planning on lighting a campfire.

If you need to procure other supplies, such as eggs, you may have to walk for 5 minutes down to the nearest shop in Viswema village.

Let us now tell you briefly about this 8-9 km stretch of motorable road between Viswema and the trekker’s point.

The rocky track climbs steadily from the village, passing through stands of pine-oak woodland that are apparently being managed for firewood.

Neat stacks of split firewood and kindling sit by the roadside and just inside the trees at the forest edge. A series of trailside signs provide entertainment and food for thought with quotes like “Animals are such agreeable friends, they ask no questions, they pass no criticism.”

Just a short way into our hike we chanced upon a house beside the track where work on a new storey had just recently begun. A ramp allowed us to walk from the road directly out onto the flat roof of the house, which would soon become the floor of the newly added storey.

The rooftop afforded us a splendiferous view of the surrounding villages, which are strategically perched atop high ground for defensive reasons. The terraced paddy fields below the villages had turned a tawny hue now that it was the post-harvest season.

Not long into our journey, we chanced upon a group of three local women (probably Angami) coming back from the woods with crude improvised walking staffs in hand for support.

The women were carrying firewood and watermelons inside their burden baskets, and they supported the heavy loads with tumplines stretched across the top of their heads.

We usually hunker down by the trailside when we see some interesting subjects approaching from afar like this, and then wait patiently with the camera primed for that perfect moment to take the shot.

Another prominent feature of the scenery at the beginning of the trek are the plantations of pollarded alder (Alnus nepalensis) trees, a practice that also occurs outside of northeast India in northern Burma and southwest China.

In Nagaland, the practice of planting alder trees has been heavily adopted by the Angami, Chakhesang, Chang, Yimchaunger and Konyak tribes.

Alder trees are a pioneer species and will rapidly colonize degraded farmland with low soil fertility - a condition often resulting from Jhum (shifting) cultivation practices in Nagaland.

With their ability to fix nitrogen in their roots, alder trees can help to replenish the exhausted soils. The deep roots of alder trees also help to stabilize sloping ground and thus aid in the fight against soil erosion.

Pollarding is when the mature alder trees are lopped at about 2 metres above the ground, causing a profusion of new shoots to emerge from the remaining bole.

When the shoots reach the desired thickness they can be cut for firewood, poles, animal fodder (for mithun, cattle etc.) and even furniture.

Alder trees may also be interplanted with crops such as maize, barley, pumpkin, cardamom, cinchona, turmeric and chillies, and their rapid rate of regrowth provides biomass to maintain the soil fertility needed to grow these crops.

You can read more the benefits of the traditional alder-based agroforestry systems in Nagaland here.

Further on we passed a wonderful display of pink blossoms courtesy of two magnificent cherry trees flanking the road.

It’s likely that the trees were Prunus nepalensis, more commonly known as the Meghalaya cherry. Many pink petals had already fallen from the trees and lay strewn across the road as we walked past.

We were lucky to have visited in December, at the tail end of the flowering season for the cherry trees. Just weeks earlier, around the beginning of November, the city of Shillong in Meghalaya state celebrated the India International Cherry Blossom Festival.

As we neared the end of the motorable road, a sign mounted on a tree informed us that we were in the Kennao clan biological reserve and it also warned not to use the forest for commercial purposes, and not to fell trees or overharvest wild vegetables.

According to this sign, the penalty for collecting forest loam or “ketsanyo” from this reserve is 5,000 rupees.

The next event of note was reaching the end of the motorable road, where we first passed a little shack built almost entirely from CGI (corrugated galvanized iron) sheets and then came to a junction, from where we could see an active construction site off to the right at the end of the track.

Instead of going towards this construction site you need to turn to left at the junction and walk along the track until you reach the foot of a man-made stone staircase that ascends into the forest. This is trekker’s point, where the hike to Dzukou truly begins.

From here it’s a challenging, energy-depleting slog up the steep, rough-hewn steps, which continue virtually uninterrupted all the way to the crest of the hill, at which point you enter the Dzukou valley.

Some of the stones are loose and wobbly so do be careful. It’s the sort of damp, humid forest environment that would usually be writhing with leeches, so have a bag of salt at the ready if you’re hiking up these steps in the monsoon season.

In our case, leeches were totally absent because it was December. The forest here is quite beautiful and mysterious so stop to admire your surroundings every once in a while.

It should take you roughly 45 minutes to an hour to reach the top, depending on your fitness level.

After the tough grind all the way up to the valley crest, you’ll eventually reach the pass where the trail enters the Dzukou valley. If you’re anything like us, this pivotal moment will probably be one of the highlights of your trip.

The sense of euphoria we experienced upon finally reaching the crest of the valley and transitioning into this surreal new world of ghostly tree skeletons and rolling bamboo-clad hills made the struggle of the climb all worthwhile. To enter Dzukou truly feels like stepping into another dimension. Perhaps this is how it feels to enter through the gates of heaven?

From the pass you still have some way to go until you reach the rest house, which lies approximately 4-5 km to the north, at the far end of this valley. It will take you 1 – 2 hours to reach the rest house from here.

The good news is that the trail is mercifully quite level all the way, so you won’t have to exert yourself too much. The path snakes along the slope of the valley, its twists and turns dictated by the valley’s folds and contours. You will cross a number of small streams and will have to push your way through a few overgrown patches of bamboo.

We had only reached the pass when the daylight was already beginning to wane, but were graciously bestowed with a very bright and luminous gibbous moon on that cloudless night.

The light of the moon beamed down upon us and bathed the trail ahead of us in its pale light, so that we scarcely even needed to use our headlamps to ensure a safe and sure-footed passage.

All the while as we trekked under the moonlight we could see the twinkling lights of the rest house, which was perched on a hill somewhere far off in the distance, ever drawing nearer.

The Zakhama trail is comparatively a more direct route to the Dzukou valley rest house than the Viswema trail. The catch is that it requires 3-4 hours of unremitting, steep uphill trekking.

It took us about 3 hours and 25 minutes to descend the Viswema trail from the Dzukou entry point, but to ascend the trail we might have taken 4 hours or so.

This trail is generally best suited to the return journey from the valley, as it is much easier to descend than ascend, and will bring you back to the main road much quicker than the Viswema trail (unless you have a driver already waiting for you at trekker’s point on the Viswema route).

Many travellers do also use this trail to hike up to the valley and that would also be our preferred option now that we’ve hiked both trails, but we only recommend it if your fitness level is reasonably high.

The Zakhama trail does come with a few hazards. Certain sections of the trail, particularly the river crossings, may be impassible during the monsoon season, as we’ll show you shortly. You may have to use the Viswema trail if you are visiting the valley during a period of heavy rains.

Assuming that you’re descending via this route, you’ll be starting your hike from the rest house. From there you need to walk back along the trail for about 10-15 until you reach a bifurcation where a green sign has been installed that reads “Alternate trek route”.

At the bifurcation you need to take the left hand fork. The path ascends steeply at first, levels out and contours along the side of the valley for a while, and then climbs up to the pass at the crest of the valley.

There’s a breathtaking view of the valley from this pass, and to the northwest you can also clearly see the abrupt transition in the vegetation that occurs between one side of the ridge, which is clothed in forest, and the other side, where dwarf bamboo dominates and reigns supreme in the Dzukou valley.

From the pass the trail enters a beautiful forest where many of the gnarled branches and twisting vines are festooned with pendulous mosses.

The damp trail descends steeply via rough-hewn stone steps covered in fallen leaf debris, which, as with the Viswema trail, are often wobbly and unstable.

There are many quotations to be seen on signs that have been fixed alongside the trail including the classic Dzukou valley quote, which reads “going to Dzukou is nothing hard like going to heaven”.

The first notable landmark on the trail is a little wooden staircase with log bannisters that somebody went to the trouble of constructing in the middle of the forest.

The trail then soon merges with a stream bed for a brief stretch and before leaving the watercourse again to the left hand side. The stream was completely dried up during our trek but following heavy rain we probably would have witnessed a very different scenario.

Once out of the stream bed and back on the trail you should soon come to an open-walled shelter. We observed a blackened log here, indicating that people do occasionally spend the night under this roof.

Some distance beyond this shelter the trail merges with the stream bed again, only this time you have to negotiate a longer and more challenging stretch of it.

We had to scramble down through the jumbled piles of rocks, logs, uprooted trees and massive boulders to again rejoin the trail further ahead. We could only imagine the scary scenario that might unfold here after a large downpour.

Next up is the big river crossing, where the trail crosses a respectably wide riverbed that is littered with rocks and boulders. Luckily for us, the watercourse was as dry as a bone, but this could be hit by a seriously dangerous torrent or flash flood following heavy rains.

A female student of St. Josephs college of Zakhama recently drowned in August 2017 while tackling the Zakhama trail, quite possibly at this very river crossing.

The girl along with eight other friends were returning from sightseeing in the Dzukou valley and were trying to cross the Dzukou river when the girl was swept away by the strong current, though her friends all managed to safely make it across the river.

Following a search by students and local volunteers her body was later recovered about a hundred feet below the spot where she was swept away.

According to the report, a group of eight other trekkers were also trapped in the valley during the same period because of the heavy rains swelling the streams.

Some distance beyond this big river crossing, the trail passes alongside an open cultivated area with a few scattered huts.

As we walked past this clearing we could hear an irate man shouting profanities in Hindi at some other person. Perhaps it was two farmers having a dispute about land boundaries, which is quite a common occurence in Nagaland.

From here the trail continues to descend until it brings you to yet another stream crossing. This one only had a trickle of water during our crossing and so it posed no obstacle to us.

It was also here at this crossing that we caught up with the Bengali couple who had set out from the rest house about an hour before us and had just crossed the stream ahead of us.

After the river crossing the trail climbs uphill for the first time, but only very briefly, and brings you up to a clearing where there’s a small rest house with a couple of hard wooden beds inside a room at the back of the building.

Heading downhill past this shelter along the trail you should soon find yourself descending a gently sloping track along the side of the valley, a welcome respite from the seemingly never-ending stone steps.

Next up is another section of stone steps, then another flat trail, and then you’ll come to a bifurcation where you’ll need to take the left-hand fork going downhill, bringing you down a flight of stone steps to join with the motorable road. A small wooden sign on a tree here near the foot of the steps points back up the steps and reads "way to Dzükou".

From here getting back to the main road is pretty straightforward. Go straight through the crossroads, past a Y-junction displaying a large green sign with white lettering that reads “way to Dzükou” and just keep following this dirt road all the way down to the river crossing. Take a right turn after crossing the river and continue downhill until the dirt road finally meets the main road.

When you reach the main road you’re about 3.8 km to the south of Zakhama village at a place marked as “Dzukou point” on Google Maps.

If you’re doing the Zakhama trail in reverse, just reverse these directions. The turn-off is at a bend in the road 3.8 km south of Zakhama and 20.6 km south of the local ground in Kohima.

Again, a shared Tata sumo zonal taxi from the Network travels AOC bus stop will be your friend in getting to the turn-off.

There are three main options as regards where to stay in the Dzükou valley; bring your own tent or hammock set up, sleep under a rock overhang down in the valley or pay your way at the rest house.

The Dzükou valley rest house or Pilgrim’s inn is a collection of about five buildings that is run, as far as we remember, by a few boys from the Southern Angami Youth Association. We may be incorrect about the organization that runs it though.

We regret to inform you that many of the staff members were not particularly hospitable or eager to help out weary trekkers arriving at the end of their long day hike to the valley, so make sure you arrive with a relatively independent mindset.

A number of dogs were being kept at the rest house during our stay but all seemed docile enough, so you have nothing to worry about there.

Signs are scattered around the property displaying arbitrary snippets and verses from the bible such as:

“Let heaven and Earth praise him, the seas and all that moves in them”.

The most amusing sign though had to be the one displaying the completely frivolous and illogical lines written by Peter in the book of Leviticus as follows:

“Be holy for I am holy.”

The rest house staff, being Nagas, are avid hunters and every morning you will probably see one of or two of them heading up into the stand of trees behind the rest house for a bird hunting session, airgun in hand.

Overhunting of birds with airguns is the main reason why it has become difficult to catch a glimpse of a bird in the Dzükou valley, or indeed in Nagaland as a whole.

But coming back to the subject of accommodation, the rest house is a good option if you're travelling light during your Nagaland trip and aren't carrying camping equipment.

The rest house offers two main lodging options; a “dormitory” or a private “VIP” room.

Regardless of which option you choose, the facilities are very bare-bones so make no mistake about it; this is true Spartan accommodation.

You should know that there is no electricity at the facility, so make sure you bring a good power bank if you want to keep your mobile device full of juice, and remember to fully charge all your camera batteries before setting out. Electric lights illuminate parts of the facility at night but these are solar-powered.

The Dzükou valley rest house also has no running water, but water for ablutions or cooking can be fetched in buckets from a small well located between the two dormitory buildings.

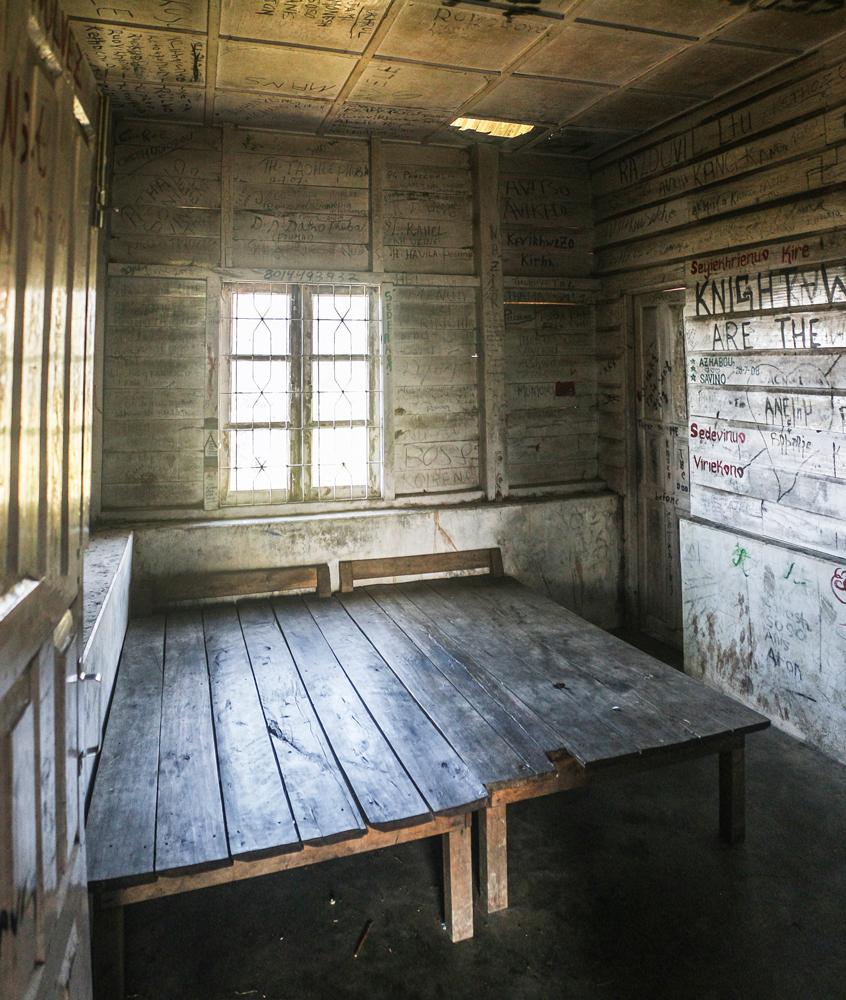

There are two separate dormitory buildings of similar size at the rest house. The interiors of both are totally unfurnished, so you will be obliged to sleep directly on the floor. The windows in both buildings are mostly intact except for the odd broken windowpane here and there.

If you’re staying in either of the dorms, you’ll have to use the shared squat toilets behind the staff kitchen, as the dorms don't have attached bathrooms.

You’ll need to fetch water from the well or from one of the blue jerry cans outside the kitchen for flushing the toilet and cleaning yourself afterwards.

The nightly rate for a floor space in either of the dorms is 50 rupees per night.

Dorm building no.1

The dormitory building on the left as you face the rest house has a concrete floor, a skylight and a relatively low, flat ceiling covered with square tiles.

The concrete floor is bad news, especially in the winter months, as temperatures often plummet well below freezing at night and much of your body heat will be sapped from underneath by a heat conductive stone or concrete floor.

We can’t make any further commentary on this dorm as we didn’t actually spend a night here.

Dorm building no. 2

The dormitory building on the right, which is the one that we spent our two nights in, has a higher, sloping roof fitted with overlapping CGI (corrugated galvanized iron) sheets. This dorm has a preferable wood floor, but it too comes with its fair share of problems.

One of the nuisances here are the resident mice, their presence betrayed by tiny mouse droppings on certain parts of the floor next to the walls.

During the night a mouse would repeatedly scuttle across our upper bodies and on one occasion a mouse scurried boldly across my exposed face, leaving me with a small scratch on my nose from its sharp claws.

To avoid obstructing the mice runs you might have to experiment a little with your location. The mice seem to habitually scurry along the walls so try to leave a little “mouse lane” between your bedroll and the wall or just try sleeping in the middle of the room.

The other major annoyance was the drips of water from the inside of the roof onto our faces, blankets and sleeping bags, which would usually begin around 7 a.m each morning. We initially thought the roof was leaky but then it dawned upon us what was really happening.

The valley was becoming so cold every night that frost was forming not only on the outside but also on the inside of the metal roof sheets.

The rising sun would then rapidly melt the frost on the roof in the early morning, causing the drips. Almost no patch of floor was safe from the drips except perhaps some small dry islands directly underneath the apex of the roof.

You can combat the dripping water issue by waking up early and starting your day before the frost begins to melt.

As we also mentioned, the centre of the room is usually a drier location than near the walls.

Lastly, although it has a cold concrete floor, dormitory no. 1 has a flat, tiled ceiling installed beneath the roof so it shouldn’t suffer as much from the drips.

The VIP rooms are found inside two small buildings that sit on a separate patch of land that is isolated from the main rest house facility by a small ravine.

It only takes approximately three minutes to walk over to the VIP rooms via a meandering walking trail.

The first building on the left as you approach from the trail has just two rooms, but the attached bathrooms here are roomier than those in the other building.

The second building has three rooms, all with cramped attached bathrooms.

All the rooms in both buildings are unfurnished except for two hard wooden beds that have been joined together to form a double bed.

Don’t expect to have security or peace of mind during the night, as the doors can’t be locked and some may even get jammed due to warping if you close them out fully.

The walls and ceiling tiles inside all the rooms have been scrawled all over with graffiti, thus conjuring up a slightly creepy "cabin-in-the-woods" atmosphere, making this the ideal setting for a blockbuster horror movie.

We initially elected to stay in one of these VIP rooms on the night we arrived at the rest house, as we figured we would feel safer with our own private room. How wrong we were.

As we lay side by side on the uncomfortable beds trying earnestly to get some shut-eye, the flickering light of our only dying candle cast eerie dancing shadows onto the graffiti-covered interior of the cabin.

We suddenly began to hear peculiar, intermittent scratching sounds that seemed to originate from inside the room, which made them all the more alarming.

Unable to ignore the disturbing noises, our attention was then drawn to a gaping black hole in one of the ceiling tiles and we figured there must have been some creature moving about in the attic that was responsible for the racket.

Knowing we were in a quiet, secluded location away from the main rest house facility only compounded our sense of uneasiness and we began to imagine that the sounds were originating from a human being lurking outside the cabin, perhaps the malevolent axe murderer of the Dzükou valley.

We eventually just psyched ourselves out completely and got so spooked that we simply couldn’t bear to remain in the cabin any longer.

We packed up all our things, snuffed out the candle and returned to the main facility, where we established ourselves for the night on the floor inside one of the dormitory buildings next to a Bengali couple that had arrived the same day as us.

We felt a lot more secure in the communal dormitory than we had felt in the lonely VIP room, even though we were in the company of total strangers.

Many travellers prefer to bring their own tent and camping equipment to the Dzükou valley so that they can have complete freedom as regards where to stay.

Some trekkers like to pitch their tents on the grassy area just outside the rest house. This isn’t a bad plan at all and if you have a clear sky there might be some great opportunities for astrophotography.

An eerie mist often blankets the lower reaches of the valley at night, leaving just the peaks of the hills poking through like islands rising out of an ocean.

You can also pitch your tent down at the bottom of the valley near the stream, where you would have a ready supply of pure water for cooking, washing and drinking. We saw old fire sites down here during our visit so people do camp there.

There’s a large rock outcrop down at the bottom of the valley that has a sizeable overhang to provide shelter from the rain. Many trekkers like to spend the night here.

We visited this rock shelter and sussed it out during our trek to the bottom of the valley, which we’ve described in detail under the section below on trekking down to the bottom of the valley.

We advise you to bring plenty of your own food supplies to the Dzükou valley, but it is also possible to order some uninspiring food from the staff kitchen.

Here food is prepared over three wood fires and the staff have a nifty blower device to stoke the fire with oxygen to get it going quickly or to revive it whenever it's struggling.

Here is what’s available from the kitchen and the pricing:

Plain Maggie – 50 INR

Vegetarian meal (rice, dal, fried potatoes) – 200 INR

Red tea – 20 INR

Coffee - 50 INR

As you can see, there is no meat or animal fat available so you will become malnourished if you depend for very long on the rest house food for sustenance.

The value for money here is also poor, so it is much wiser to import your own food and cook hearty meals, with plenty of butter, ghee and animal fat, over a campfire during your stay.

The rest house staff members do actually cook meat such as chicken and pork for themselves most evenings, but seem to consider it too scarce and valuable a resource to prepare for guests.

Boiled water for drinking purposes can be obtained free of charge from a large metal teapot inside the staff kitchen.

If you are camping far away from the rest house the unadulterated streams and rivulets down in bottom of the valley will supply you with plenty of water, so don’t feel the need to import too much.

If you plan to prepare your own meals over a wood fire, you can buy pieces of split firewood from the rest house.

The rate is 10 rupees per piece or 100 rupees for a bundle of 10 pieces, which can add up quickly depending on long you want to keep the fire going.

If you’re just lighting a fire for cooking purposes (not for campfire songs, staying warm etc.) you won’t need to purchase as many pieces (we got away with buying just 4 pieces for our fire the first night), but if you want to keep a fire blazing all night for warmth, you’ll need to purchase multiple bundles and the financial expense will be significant.

For keeping warm, it’s more sensible to bring a good sleeping bag and make better use of your own body heat.

If you need to prepare kindling from the split firewood to get the fire started you can ask if you can borrow one of the staff members’ dao (machete).

Some people avoid the firewood charges completely by collecting dead wood from the forest while hiking up to the Dzükou valley. It would be burdensome to convey the wood all the way from here though.

There is also a stand of oak-rhododendron forest on the hillslope directly above the rest house, as the valley is not entirely treeless. If you venture up into the wooded area behind the rest house you may be able to procure some good firewood.

You can also walk back out along the trail leading to the rest house in search of firewood. We found a few good thicker pieces lying on the trail itself and we also found a plethora of dead flower stalks and dry bamboo shoots among the trailside vegetation, which made excellent kindling.

If you’re planning to camp and cook down at the bottom of the valley, remember that firewood will be very scarce or non-existent here due to the complete absence of trees. The only things you might be able to use as fuel here are the dead grasses and bamboo shoots.

Another great option of course, that doesn’t require you light a fire at all, is to bring a gas camping stove and plenty of fuel. You can also use solid Hexamine fuel tablets with a folding pocket stove if you prefer that type of set up.

As regards a cooking vessel, we brought our stainless steel cooking pot that we always carry with us on the road. This pot has seen years of (ab)use and is still going strong. We ate our meals with a spork.

If you stay at the rest house you will unfortunately have to pay a park entry fee.

Here are the differential rates:

Domestic & foreign tourists: 100 rupees

Locals: 50

Neighbouring villages: 20

If you camp down in the valley and never have contact with the people at the rest house it is possible that you won’t be asked to pay the entry fee. We’re not entirely sure if the staff try to enforce the fee for every visitor or not.

Although a lot of people bring camping equipment to the Dzukou valley, the truth is that you can rent or buy virtually everything you might need from the rest house, and still the cost of your stay shouldn't exceed that of a budget hotel room.

Our bill came to just 470 rupees per person for two nights, though we did bring our own eating utensils, cooking pot and one sleeping bag.

You can rent blankets, pillows and foam sleeping pads from a small room opposite the staff kitchen. The rate for all these things is a once-off payment of 50 rupees per item, not per night.

The whole enterprise is however a bit of a scam because both the blankets and sleeping pads are excessively thin and are woefully inadequate for the extremely cold nights in the valley, especially in wintertime.

We required a whopping five blankets and two sleeping pads to stay adequately warm inside the dorm, and that was while already wearing all of our winter clothes, including puffy down jackets, thermals and woolly hats.

You can also rent cooking equipment from the rest house such as a large cooking pot (50 rupees) and a set of cooking utensils (100 rupees).

You can also hire a guide from the Dzukou valley rest house. Some people hire one for the return journey back to the road, or for exploring the valley. The rate is 1,500 rupees per day.

#1 - Rejoice in the jaw-dropping views from the rest house

The first thing you’ll probably notice when you get to the rest house is that there’s a perfect view of the Dzukou valley from the grassy patch of land next to the property.

You could easily spend a few hours soaking up the sun and enjoying the panorama from here and indeed, that's all some visitors ever do.

We found that the mornings and evenings yielded the best light for photography. The lighting around midday was very undesirable and resulted in unusable images.

Unfortunately we were too snug under a heap of blankets in the dormitory to haul ourselves out of bed into the freezing cold morning air for the sunrise, but we did witness a phenomenal sunset on our second evening.

For the best chance of witnessing a perfect sunset you should try to visit outside the monsoon season, as there’s a better chance of cloudless skies during these times.

The rest house is one of the best places to experience or photograph the sunset from because the sun sets behind the mountains off to the west, but you can certainly experiment with different locations if you have the time.

#2 - Visit the ghost cave

There is reportedly a cave in the Dzukou valley, known as the ghost cave or “bhoot gufa” and it is said to only be a 15-minute walk from the rest house.

The cave supposedly extends for 1 km so you would need to bring a good headlamp or flashlight if you want to explore it properly.

We didn’t get a chance to visit this cave as we only stayed for one full day in the valley, but the cave has been briefly mentioned in a few articles, and one of the staff members at the rest house also told us there was a cave nearby.

You’ll have to ask the staff or other trekkers for more precise details and directions once you arrive, as we couldn’t find any detailed information about the whereabouts of the cave online.

#3 - Hike to Japfu peak

There is a viable trekking route from the Dzükou valley to Japfu peak, the second highest peak in Nagaland.

However the trail is reportedly heavily overgrown with thick bamboo so there's a good chance of getting lost or losing the path. It would probably be best to hire a guide if you plan to hike to Japfu peak directly from the valley.

If you want to tackle Japfu peak from Kigwema village, which is the route that we took, you should read our detailed article on how to summit Japfu peak without a guide.

#4 - Trek to the bottom of the valley & visit the cross

It would be a shame to visit the Dzükou valley and only spend the entire time relishing the view from the rest house. Some time should of course be allocated to this activity, but there is more to accomplish.

If you’re staying at the rest house, trekking down into the valley is the obvious thing to do once you’ve familiarized yourself with the rest house and spent your first night there. It’s a good idea to tackle this excursion on the morning following the day of your arrival.

Once you reach the flat terrain at the bottom of the valley, you can also climb to the top of a small hill that is crowned with a prominent Christian cross.

The cross is clearly visible from the rest house in the morning but later on in the day, when the weather is sunny, it almost becomes invisible due to a trick of the light.

The trail to the valley floor begins on the west side of the rest house, passing through bamboo scrub and immediately descending into a trough, then ascending out of the trough to bring you to a bifurcation.

If you take the left track you’ll be taken to the helipad.

The Dzükou valley helipad was commissioned by Nagaland’s department of tourism in a bid to promote tourism in the state.

There exists a Dzükou valley chopper service for the lazy, time-strapped or for those unable to trek to the valley on foot, such as the elderly or differently abled. The service doesn’t operate daily but on an as-needed basis, whenever there is sufficient demand.

It’s likely that the main flower blooming season and especially the period of the annual Hornbill festival would see the most patronage of the service.

A disproportionate number of the foreign Hornbill festival attendees are elderly people, many of them pushing into their 60s and 70s, and hence they would require the assistance of a helicopter to reach the valley.

If you wish to go by helicopter, you can try booking one through a tour operator or a Government tourism counter. According to this article, the service operates from Kohima.

Though the project has undoubtedly benefited moneyed elderly and disabled tourists, it has also sparked plenty of controversy.

Many people (rightly) feel that the immaculate condition and beauty of the Dzükou valley is marred by modern structures and eyesores like helipads and that the area will be further desecrated by the subsequent influx of tourists.

The fear is that tourists will pick the precious lilies and wildflowers, trample the fragile vegetation, pollute the pristine rivulets with human excrement, leave plastic bags and other refuse strewn about the scenery, start wildfires out of carelessness, cut down the few remaining trees in the valley for firewood, poach the already scarce birds and animals, scrawl graffiti over sacred rocks, and commit other insensitive acts of vandalism.

There is a Facebook group called “Naga Global Campaign To Save Dzükou Valley, whose mission is to save the valley from “development ruin”.

Many members of the group feel that the number of authentic adventure travel experiences in Nagaland is diminishing rapidly because of attempts to open up the state’s attractions to mass tourism.

Certainly the attraction of these places partially lies in their secrecy, offbeatness and inaccessibility, and much of the current appeal will be lost if the Dzükou valley becomes another popular, easily accessible attraction on the world tourist circuit.

We must inform you that there is a sensational viewpoint of the Dzükou valley from the steeply sloping ground just below the helipad. Descend as far as you dare but take care not to go over the edge of the deadly precipice!

Coming back to the bifurcation, if you continue straight instead of turning left you’ll remain on the trail that leads all the way down to the bottom of the valley.

This track first passes through an enchanting scene; a copse of dead standing trees, their lifeless, partially debarked boles and branches stretching high into the air, like arms reaching for the heavens.

But why this morbid scene of lifeless tree skeletons? It’s likely that these trees were killed in one of the recent forest fires that devastated the valley, as is suggested by some of the evidently scorched and blackened trunks.

When the trail emerges from this stand of dead trees a magnificent vista of the valley is revealed.

The descending trail roughly parallels the course of a stream flowing at the bottom of a small, steep-sided gorge off to the left hand side.

Further ahead you can take a diversion from the trail to a number of precarious rock outcrops at the edge of this gorge, which serve as agreeable vantage points.

Continuing the descent from here, you will soon reach the flat valley floor, where the bamboo vegetation grows less vigorously than in the valley’s upper reaches (or at least it was in our case), hardly exceeding knee-height.

A few scattered standing stones that appear to have some kind of spiritual, political or religious significance sit next to the trail in this part of the valley, though many have sadly been disfigured by the scribbles of amateur graffiti artists.

Signboards have also been erected next to the trail, displaying biblical quotations that are taken out of a completely different context, yet are intended to appear relevant in the context of the Dzukou valley.

One of the signs reads:

“The grass withers and the flowers fall but the word of God stands forever”.

Even this remote mountain valley is not free from the far-reaching influence of Christianity.

.jpg)

You will soon come to a key landmark of the valley, which is the small, wooden Dzukou valley bridge, allowing you to traverse a shallow, gurgling pebble stream without having to leap over it to the far bank or wet your feet.

.jpg)

You might wonder why a bridge is needed for such an easily fordable watercourse, but just immerse your bare feet and ankles into the frigid water here for a few moments and you will soon surely understand.

The utterly intolerable sensation that arises in the ankle region after just a few seconds of immersion can only be described as total agony. When that horrendous pain kicks in, your only preoccupation will be in finding the fastest way possible back to dry land.

Something you might observe here at this site is that some of the submerged pebbles in the water below the bridge have people’s names indelibly scribbled on them, perhaps the result of the authors’ attempts to immortalize themselves in the eternal flowing waters of the heavenly Dzukou valley.

Just beyond the bridge the trail leads to a sizeable rock outcrop, which is where trekkers often camp if they’re not staying at the rest house.

Notwithstanding the refuse left by previous campers that litters the site and the unsightly graffiti that mars the rock, it's not a bad place to spend the night.

The rock has a substantial overhang, which extends out far enough to keep campers dry during inclement weather. A tarpaulin has also been rigged up to expand the area of sheltered ground underneath the overhang.

We found several bags of iodine-fortified salt (table salt with small amounts of iodine added to prevent iodine deficiency) tucked into a nook in the rock face to keep them out of the rain.

We assume that people have kept the bags of salt here for the monsoon season, a time when trekkers would be in dire need of the salt to combat the armies of voracious bloodsucking leeches.

You can also clamber up on top of this rock from around the side, where you can enjoy a fine sweeping view of the valley, looking back in the direction of the rest house.

Regrettably, the upper surface of the rock has been very badly defaced with ugly graffiti and deep etchings by vandals.

Up here atop the rock there is also a plaque embedded by the Southern Angami Youth Organization, which details the names of the executives holding the various positions within the organization. (president, vice president, treasurer, accountant etc.)

If you continue on from the rock shelter, the trail intersects the stream again and you will have to cross it if you wish to visit the cross on the hilltop.

There is no bridge this time but you can use the stepping-stones to take you across, thus saving you the hassle of removing your shoes and socks.

If the prospect of using the stepping-stones is too daunting you can just remove your footwear and wade across the icy-cold stream to the bank on the other side, but be prepared for the ensuing cursing and unbearable pain in the ankles.

Once over the stream, it’s just a short but challenging hike up a steep hill through dense swathes of bamboo until you reach the cross at the apex.

Once you surmount the hill you will observe that the cross employs a very basic design and stands probably no more than 15 feet in height. It’s comprised of a rudimentary metal framework covered on one side with pieces of rusting sheet metal to form the outline of a cross.

The structure probably has to withstand strong gales from time to time so there are a few stays and supports anchoring it to the ground. Unsurprisingly, there are more signs erected around the cross that display trite biblical quotes.

The main reason to make the climb to this hilltop however is neither the cross nor the biblical quotes but the awe-inspiring panoramic view that the location commands. It’s worth coming here for that reason alone.

Since we were carrying our ultra-lightweight aluminium tripod, we decided to set it up here and take a timer countdown shot with both of us overlooking the valley.

As we looked out across the magnificent valley it soon dawned upon us that we had the entire place completely to ourselves. There wasn't a human soul in the valley that day apart from us and it was incredibly quiet and peaceful. We were incredibly grateful that the place was not overrun with tourists.

Returning back to the rest house is an almost entirely uphill affair after leaving the flat part of the valley, and the walk is surprisingly challenging despite the relatively gentle incline. The increased difficultly probably arises from the slightly rarefied air at this altitude.

The Dzükou valley in Nagaland is one of the most memorable attractions in northeast India and holds its own as an outstanding offbeat destination for adventure travellers.

You are virtually guaranteed a wonderful adventure here and at the same time you will find peace, solitude and blissful scenery, even if you visit the valley during the relatively busy times.

For the time being at least, the valley is still relatively unspoilt and is well worth visiting but we encourage you not to postpone your visit for too long, as dramatic changes may be afoot with respect to tourism in the state of Nagaland.

If the valley becomes accessible and known to a larger segment of the tourist market, it is likely that the Dzükou valley experience will be greatly diluted and much of the appeal will be lost.

If you enjoyed this guide or found it useful, please share it other travellers. Do you have a favourite offbeat trekking destination in northeast India? Are you optimistic about the future of the Dzükou valley? Please feel free to add to the discussion in the comments section below.

Pin this article!

JOIN OUR LIST

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

ABOUT US

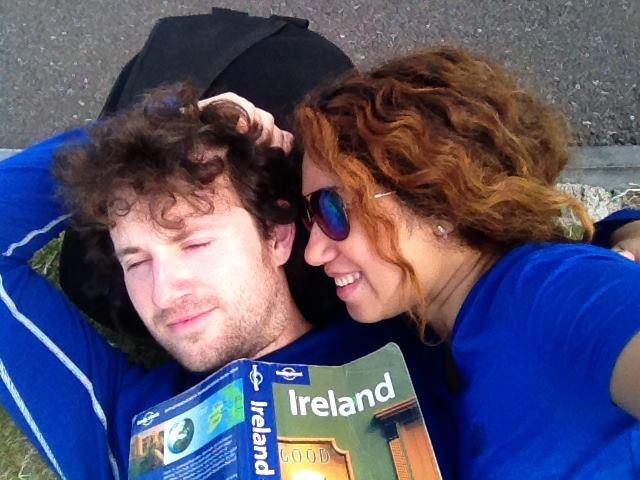

Our names are Eoghan and Jili and we hail from Ireland and India respectively.

We are two ardent shoestring budget adventure travellers and have been travelling throughout Asia continuously for the past few years.

Having accrued such a wealth of stories and knowledge from our extraordinary and transformative journey, our mission is now to share everything we've experienced and all of the lessons we've learned with our readers.

Do make sure to subscribe above in order to receive our free e-mail updates and exclusive travel tips & hints. If you would like to learn more about our story, philosophy and mission, please visit our about page.

Never stop travelling!

FOLLOW US ON FACEBOOK

FOLLOW US ON PINTEREST

-lw-scaled.png.png)